— by Jens Kruse —

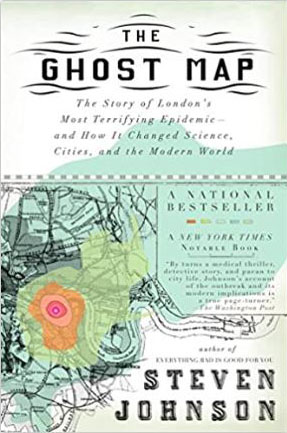

Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map (2007) is, as the subtitle says, The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic — and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World.

Johnson, who is the author of several books and a Distinguished Writer in Residence at New York University’s Department of Journalism, introduces his book as follows.

This is a story with four protagonists: a deadly bacterium, a vast city, and two gifted but very different men. One dark week a hundred fifty years ago, in the midst of great terror and human suffering, their lives collided on London’s Broad Street, on the western edge of Soho.

This book is an attempt to tell the story of that collision in a way that does justice to the multiple scales of existence that helped bring it about: from the invisible kingdom of microscopic bacteria, to the tragedy and courage and camaraderie of individual lives, to the cultural realm of ideas and ideologies, all the way up to the sprawling metropolis of London itself. (xv)

Johnson opens his story, in August of 1854, with a discussion of London’s scavengers, 100,000 of them in a city of 2 million, the specialized recyclers of the city’s detritus and waste. There are “bone-pickers, rag-gatherers, pure-finders, dredgermen, mud-larks, sewer-hunters, dustmen, night-soil men, bunters, toshers, shoremen” (1). Some of these names are descriptive enough, others are not. I confess, for instance, that I did not know that “pure-finders” were collectors of dog turds. It turns out that dog turds

were a substance that was of great value in the leather tanning process.

But the scavenging specialty that is of greatest interest for the story that Johnson will tell are the “night-soil men.” You see, London in the middle of the 19th century, a metropolis roughly a third of the way through the Victorian Era, did not have sewers. Its inhabitants stored their excrement in cesspools near their houses, or, if no cesspool was available, in their basements. Night-soil men, for a fee, came to empty these storage places and then conveyed their harvest to the countryside where they sold it to farmers for fertilizer.

When a cholera outbreak started in Soho in late August of 1854 — an outbreak that decimated the Broadstreet neighborhood, killing more than 600 people in less than a week, and 3000 in London outside of Soho – two men living in the neighborhood started investigations to determine the cause of the outbreak.

John Snow had risen from a modest background to become a well-known physician. He had single handedly developed techniques of safe and reliable anesthesia and attended at the birth of Queen Victoria’s eighth child. But he remained dedicated to his patients in his neighborhood and his investigations into the cause and transmission of cholera.

Henry Whitehead, a clergyman at St. Luke’s church, made his rounds to his parishioners, both healthy and sick, and, tracking the cascade of cases, tried in his own way to make sense of the outbreak.

At the time, there were two camps regarding the cause of cholera: the contagionists and the miasmatists. The miasmatists, the larger and more influential camp, held that it was essentially bad air that caused cholera and other epidemic diseases, and certainly London with its thousands of cesspools often stank to high heaven, especially in the summer. But contagionists, Snow prominent among them, argued that cholera was

caused by some as-yet-unidentified agent that victims ingested, either through direct contact with the waste matter of other sufferers or, more likely, through drinking water that had been contaminated with that waste matter. Cholera was contagious, yes, but not in the way smallpox was contagious. Sanitary conditions were crucial to fighting the disease, but foul air had nothing to do with its transmission. Cholera wasn’t something you inhaled. It was something you swallowed. (71-72)

Ironically in the very year of the 1854 outbreak an Italian scientist, Filippo Pacini, had isolated Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium that causes cholera, but his work was ignored and Snow did not know of it. So he and Whitehead had to rely on statistics, geography and demography to trace the progress of the disease, eventually producing the “ghost map” of the book’s title, a map of cases and deaths that made it possible to “see” the epicenter of the outbreak.

It turned out to be the Broad Street pump, which the inhabitants of this neighborhood had treasured for its good water, but its well, it turned out, had become contaminated with the excrement of a nearby cesspool. Its water, once clean, had now become infested with Vibrio cholerae.

The consequences of the discovery of the cause of cholera were profound. By 1865/66, London had constructed the most comprehensive and modern sewer system in the world. Other cities followed suit, although not all of them as fast. Cities on the scale of London and much larger, which had once been in danger to perish in their own excrement now became viable. Mankind became more and more urbanized. In the last decades of the

nineteenth century, “the germ theory of disease was everywhere ascendant, and the miasmatists had been replaced by a new generation of microbe hunters, charting the invisible realm of bacterial and viral life” (213). Epidemiology as we now know it had its beginnings in Snow’s and Whitehead’s investigations.

Close to the end of his narrative, Johnson reflects:

But if our current prospects seem bleak, we need only think

of Snow and Whitehead on the streets of London so many

years ago. The scourge of cholera then seemed intractable,

too, and superstition seemed destined to rule the day. But in

the end, or at least as close to the end as we have gotten so far, the forces of reason won out. The pump handle was removed; the map was drawn; the miasma theory was put to rest; the sewers were built; the water ran clean. This is the ultimate solace that the Broad Street outbreak offers us in our current predicament, with all its unique challenges. (255-

256)

Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying

Epidemic — and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World.

(New York: Riverhead Books, 2007) is obtainable through Darvill’s

Bookstore.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**