||| FROM ELISABETH ROBSON |||

’Tis the season of giving, the season of gratitude, the season of appreciation. Let me know in the comments who and what you most appreciate in our little part of the world.

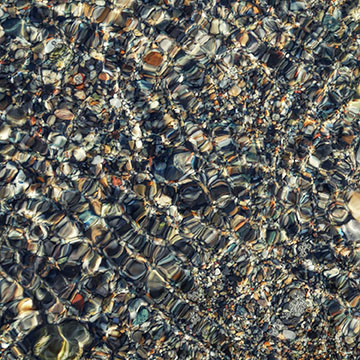

Amoebas

Yes, I’m grateful for amoebas. Why? Amoebas are amazing. They are one of Earth’s earliest lifeforms—they evolved about 750 million years ago. Amoebas have roughly 13,000 genes (compared to our 20,000 or so), and our human genome contains about one third of those amoeba genes—amoebas are our kin. Amoebas figured out how to replicate, code proteins, create a cell membrane (for their single cell), move, metabolize food, and sense and adapt to their environment (sensing light, heat, chemicals, vibration, and more). All of this we have inherited from amoebas.

Amoebas are single-celled organisms that move using pseudopodia (false feet)—how cool is that?!—and are considered a type of zooplankton when they live in lakes, ponds, streams, and even tap water. They play a vital role in ecosystems by controlling bacteria and interacting with many other life forms.

We would not exist without the amoeba. Yet, our way of life threatens these tiniest of life forms—for instance, microplastics can accumulate in amoebas, disrupting their normal function and killing them, and other forms of chemical water and soil pollution can likewise disrupt their natural habitats and poison them.

I’m grateful for the amazing genius of amoebas.

An amoeba is many orders-of-magnitude more subtle and sophisticated than our technological machines. — Tom Murphy

Oxygen

I wake in the morning and take a breath and I’m grateful for oxygen. Without oxygen, none of us would be alive. Our cells use the oxygen we breathe from the air to break down food molecules and generate energy.

The oxygen we breathe is in the atmosphere primarily because of phytoplankton and trees. Phytoplankton are what we call the tiniest plants who live in the world’s water; most are single-celled organisms, and all absorb sunlight and use photosynthesis to convert carbon dioxide into energy, just like land plants and trees do. In this process, they produce oxygen. The oxygen dissolves into water, and some of that oxygen is released from the water into the atmosphere and becomes the air we breathe.

Trees breathe in carbon dioxide through tiny pores on their leaves called stomata. They use this CO2 along with sunlight and water in photosynthesis to build their bodies, and exhale the freed oxygen back into the atmosphere for the oxygen-breathing animals of the world to inhale.

The world’s forests produce about 28% of the Earth’s oxygen, while the majority of the rest is produced by phytoplankton. Trees and phytoplankton are therefore directly responsible for the oxygen we all breathe every moment of our lives.

Phytoplankton are the bottom of the food chain in aquatic ecosystems; without them there would be no trout, no salmon, no shrimp, no crab, no orcas. The oceans, lakes, and ponds would be empty of life without them. Phytoplankton and many other aquatic animals and plants are threatened by ocean acidification, climate change, increased precipitation, drought, development, and pollution.

Likewise, the world’s forests are threatened, with original old-growth forests reduced by almost 80%. Most old-growth forests are being cut down for industrial agriculture, mining, road building, and lumber.

We would not exist without phytoplankton and trees because we would not exist without oxygen. I give thanks for the oxygen that fills my lungs and the wild beings who make that possible.

Water

Do you know how long you could survive without water? Do you know where your drinking water comes from?

Most of us here in San Juan County are lucky enough to have clean (or clean-ish) water to drink. Our water comes from wells that tap into underground aquifers fed by rainwater that filtered through layers of soil and rock perhaps a few decades ago (or longer!). We are lucky to have this old water; for most of us, it is relatively free of the chemicals and other contaminants we find in surface water and rain water. That said, some unlucky people here in the county have well water contaminated with “forever” chemicals like PFAS that can disrupt hormones, increase cholesterol levels, and increase the risk of thyroid disease, and testicular and kidney cancers.

A 2017 study found that 94% of tap water samples in the U.S. were contaminated with microplastics. Even if the water coming up from our wells has no plastic, it can easily be contaminated with plastic on the way to your water bottle. Microplastics have been found in every part of human bodies ever tested, including our brains, our reproductive organs, our blood; even unborn fetuses contain microplastics now. Some of that comes from the water we drink.

All the other life we share the land and water with here in San Juan County is thus also contaminated with microplastics and other chemical pollutants they ingest in the water; from the tiniest fish to the largest whales, from the bacteria in the soil to the vegetables we eat from the local farms to the trees we love, the birds, the deer, the rabbits, our pets—they, too, are all drinking chemicals and plastics in the water just like we are.

We humans can survive only a few days without water, and yet so many don’t even know where our water comes from. We turn on the tap, and voila, there it is. Do you know the watersheds of the Salish Sea? Do you know the streams and wetlands in the county? Do you know all the living beings who rely on this water? This water that is 4.5 billion years old; water that circulates continuously through all of the bodies of the world? Water that goes from air to cloud to rain to the ground, is drunk up by a tree and evaporated into the air again, or drunk up by you and then released into the septic tank and then to the ground and then to a tree and then to the atmosphere?

I love this water, and I am unendingly grateful for it.

Wind

San Juan County can be a windy place. I’ve heard some say they “hate the wind.” The wind can topple trees and cause damage to our human-made structures and sometimes even to ourselves, but the wind is a gift.

I remember well the heatwave of June, 2021, when temperatures soared to 103 degrees at my house. For three days we sweltered in the oppressive, still heat—and we were lucky compared to others in the Pacific Northwest who suffered in temperatures of up to 121 degrees.

On the final day of the worst of the heatwave, I began to feel a breeze off the ocean again. I was so grateful for that wind, I yelled out loud, “I love you wind!” How lucky are we that we live on the edge of the Pacific Ocean with warm-ish ocean breezes to moderate cold temperatures in winter, and cold-ish ocean breezes to keep us cool in summer?

The wind is critical for San Juan County’s ecology, too. It carries seeds and disperses pollen. It helps to mix air masses, distributing nutrients and oxygen throughout the atmosphere. It churns ocean waters, bringing nutrient-rich deep water to the surface, boosting marine life. It strengthens plants and trees over time by forcing them to build stronger stems and trunks. And when the wind does knock over trees, it opens the forest floor to more light, stimulating growth, and creating areas of younger trees and plants among older forested areas. The snags feed and house woodpeckers and owls, and the rotting trunks become nurse logs for the next generation of trees and understory. We might bemoan the wind for knocking over trees, especially when they fall on our structures, but healthy forests are a mosaic of trees of different ages that support a greater diversity of wildlife.

I sometimes head out to Iceberg Point on windy days to stand on the rocks, brace myself against the force of the gale like old spruce trees bent but not broken from years of windy winters, and tell the wind how grateful I am.

Pacific Tree Frogs

The Pacific tree frog is Washington State’s state amphibian. They are small—less than 2 inches long—but make a big sound when the males sing on spring evenings at the County’s ponds, wetlands, and even roadside ditches, where they breed. The frogs spend the rest of the year in woodlands, meadows, and gardens. In spring, when they migrate to the ponds and wetlands, I find countless frogs smashed flat on the roads where they’ve attempted to cross from their winter habitat to where they hope to breed. Every flattened frog carcass breaks my heart.

Pacific tree frogs are considered a keystone species, meaning they play a vital role in the ecosystem, and in the food web. The frogs are an indicator species; if their populations are increasing, the ecosystem is generally healthy. If they are decreasing, that’s a sign something is wrong. Amphibian populations, including frogs, are declining worldwide at a rapid pace and one in three species is threatened with extinction.

The frogs are critical to the survival of many other species. They are a primary food source for fish, hawks, owls, and snakes. Tree frog eggs and tadpoles are eaten by fish, dragonfly larvae, diving beetles, salamanders, snakes, and birds. The frogs are insectivores, so they help control insect populations, along with eating algae and decaying vegetation.

In other words, these sweet and lyrical frogs are part of an unimaginably beautiful, mysterious, and unfathomable web of life that connects us all.

Late wintertime, we all wait for the first singing of the frogs; it’s a sure sign that spring is coming. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t love the sound of the frogs as they serenade the twilight, or delight in finding a tree frog hidden in a bush or beside a pond.

Did you know that frog skin is permeable, allowing water to pass through easily? This makes frogs extremely sensitive to chemical toxins, so you must not handle a frog as any chemicals on your skin will pass into the frog. Lawn chemicals and water pollution are a constant threat to amphibians of all kinds, and especially to tiny Pacific tree frogs. Other threats include lawn mowers, cats, bullfrogs, and of course cars and roads, which all take their toll on tree frogs.

The Pacific tree frog reminds me of the intricate connections between all life here in San Juan County, the threads of the web of life. They are so fragile, so delicate, and we break them at our peril. Every spring, when the tree frogs sing, I smile, and tell them how grateful I am for their song.

My gratitude extends to all the beings in the web of life, all the vital processes of Earth’s ecosystems, and all the beauty—nature’s art—that we are lucky to experience here in San Juan County.

I look forward to reading about the things you readers are grateful for.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Thank you Elizabeth,well written and. Reminds us of the significant things of life beyond politics @nd daily issues.

I’m thankful for Lin McNulty and the Orcasonian. Wow, is she awesome or what? Why, I was just talking to my girlfriend the other day, and she remarked something to the effect that she’s the greatest thing that’s ever happened to the San Juans.