— Book review by Jens Kruse —

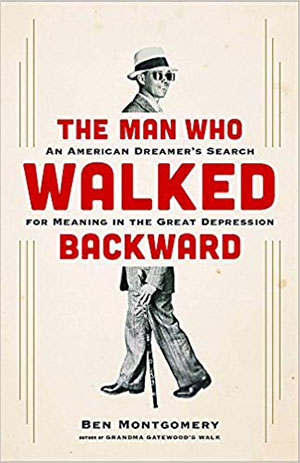

Why would anyone want to read a book with a title suggesting that it is about a celebrity-seeking stunt artist, that it tells a story too frivolous for our serious times? And yet, in this review, I will urge you to read Ben Montgomery’s The Man Who Walked Backward. An American Dreamer’s Search for Meaning in the Great Depression (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2018).

Why would anyone want to read a book with a title suggesting that it is about a celebrity-seeking stunt artist, that it tells a story too frivolous for our serious times? And yet, in this review, I will urge you to read Ben Montgomery’s The Man Who Walked Backward. An American Dreamer’s Search for Meaning in the Great Depression (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2018).

Why should you read it? Well, let’s start with the author: Ben Montgomery is the story teller who, in 2014, gave us Grandma Gatewood’s Walk, the inspiring story of the 67 years old grandmother who thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine.(1) But the second, and maybe even more important reason, is contained in the subtitle of The Man…: An American Dreamer’s Search for Meaning in the Great Depression.

Plennie Wingo’s story unfolds against the backdrop of the Great depression, its antecedents and its consequences. It is a walk, backward, through the history of North America and the U.S.A. And once Plennie gets to Germany, from where he walks through Europe to Turkey, it becomes a glimpse of that country’s historical moment as well.

As the post-World-War-I boom gives way to the crash and the great depression, Wingo loses his restaurant and watches as the “public appetite for all things trivial could not be quenched” (29). Sure, Lindbergh earned his fame by doing something heroic, but others garnered their episodes of fame by sitting on poles or by pushing a peanut to the top of Pike’s Peak with their nose. So why shouldn’t he, Plennie Wingo, find fame and fortune by walking backwards around the world?

And so he walked, backwards, from Ft. Worth to Boston, where on the S.S. Seattle Spirit he worked his way across the Atlantic to Hamburg, Germany. From there he walked to Berlin and on to Istanbul, Turkey. There he was imprisoned and finally persuaded by the American ambassador that to go further would cost him his life. So he took a ship back to New York, caught a ride to Los Angeles, and from there walked backward to Ft. Worth, completing a sort of circle.

On his journey, he meets friendly and hospitable people and others who are suspicious or try to take advantage of him. Everywhere, though, he observes his surroundings and listens to stories. And so, as Montgomery makes us walk with him, we learn about racial violence and lynchings; the killing and removal of the Plains Indians and the decimation to near extinction of the buffalo herds that sustained them; about rapacious farming and the dust storms that followed; about reckless mining and environmental degradation; about bank failures and bank robbers; about Prohibition and crime syndicates; and so much more.

When Wingo reaches New York we hear: “He had left the dust storms in Texas and Oklahoma, backed past barren fields and stalled tractors in Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana, past shuttered factories and mines in Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania, and hungry men and women along the way. (…) But nowhere was the collapse as obvious as in New York” (176-176).

He gets to Germany in early 1932 and, after spending some time in Hamburg, he walks, “rückwärts,” to Berlin. There, the economic situation is worse than in the United States, and the political situation is ominous: “Democracy hung in the balance” (205). There he learns about the swift rise of a charismatic party chief:

“He was a chauvinist. He was a fascist. He was a nationalist. People loved him. Those who didn’t were scared of those who did. Those who did came by the thousands to see him (…) The establishment treated him like a joke at first, an outlier and extremist, until their laughter was stifled by the sheer number of people who believed what he said. (…) He promised an assortment of government reforms, but chief among them, at the top of his list, was the jingoistic and immeasurable vow that he would make Germany great again” (204-205).

Plennie Wingo never made a fortune with his backward walk, but he did achieve a modicum of fame. In 1976, 45 years after his walk, he appeared on the Johnny Carson Show to promote his intention to walk, at the age of 81, backward from San Francisco to Santa Monica. He died, pretty much penniless, in 1993, aged 98.

The book is: Ben Montgomery. The Man Who Walked Backward. An American Dreamer’s Search for Meaning in the Great Depression (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2018).

It is available at the Orcas Library and at Darvill’s bookstore.

NB: Ben Montgomery will give a book talk and reading, and sign copies of his book, at the Orcas Library this Friday, October 26, at 6:00 p.m. For more information, see the Library web site.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**