— Book review by Jens Kruse —

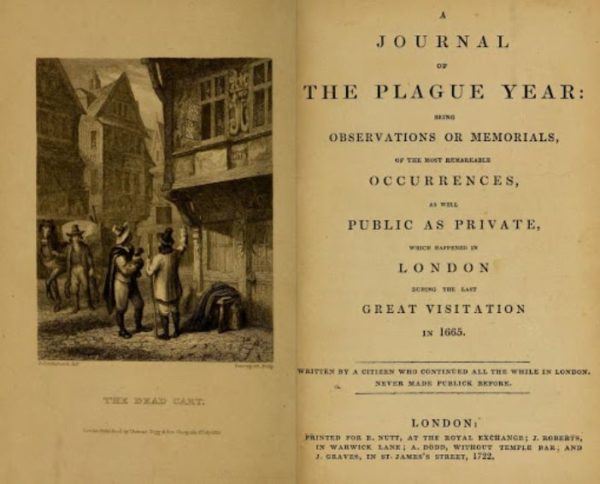

Daniel Defoe’s 1772 account of the 1665-66 outbreak of the bubonic plague in London makes – shall we say: interesting – reading at our current moment. This Great Plague killed an estimated 100, 000 people, about a quarter of London’s population.

Defoe was 5 years old at the time of this plague outbreak, so in order to present a first person account when he writes the book in the years before its publication he creates a fictional narrator who experiences the outbreak first-hand. For that reason, the book is sometimes referred to as a novel, but it is an account that is based on documentary evidence and eye-witness observation, probably based on the journals of Defoe’s uncle, Henry Foe, a saddler who lived in the Whitechapel section of London, just as Defoe’s narrator. The book was originally published under the initials H. F.

When the plague starts, many people — those who can afford it, those who have second houses – flee into the country. Our narrator, for a variety of reasons, decides to stay. So he is on the ground and can describe the medical, social, and economic effects in great detail and with impressive verisimilitude. He takes us along into the various neighborhoods of London as he roams the city and observes the ravages of the disease: the people shuttered in their houses, the healthy with the sick; the plaintiff wails of pain and grief, the individuals crazed by pain racing through the streets and falling down dead, the sufferers throwing themselves out their windows to their death; the workers loading bodies into dead carts and burying them at night, first in church yards, then in mass graves. In addition to these impressions he provides us with data: the weekly death

lists, with their ever-growing body count.

He discusses the government’s – the magistrates’ and Lord Mayor’s – response, sometimes approvingly and sometimes critically. He quotes their declarations, edicts, and policies at length, and this gives us a sense how the authorities are struggling to contain, ameliorate, and defeat the plague. In

particular, he weighs the benefits and drawbacks of shuttering a house with a diseased person in it together with his or her still healthy family.

He describes how the medical services are inadequate and quickly overwhelmed, how the government failed by providing only two pest houses. He explains that the knowledge of the disease’s transmission is fragmentary at best and flatly false at worst. He shows us how, especially in the early stages of the outbreak, all manners of quacks enrich themselves by offering fake cures.

He shows how the poor people are particularly affected: getting the disease, and, even if not, losing their jobs and their livelihoods first, starving, even if staying healthy.

He makes clear that the disease strains the fabric of society: the court and much of the aristocracy leave London, the people in the country resent the people fleeing the city, bringing them the disease and straining their resources. But he also recounts many acts of generosity and charity.

He describes the economic impact: in London, England, and internationally. Trade collapses, workshops and factories shutter. But markets continue to operate and basic foodstuffs are still available.

He recounts how false information and rumors circulate rapidly and how this leads many people to make the wrong decisions and engage in destructive and self-destructive behavior.

It is a captivating and terrifying tale, sometimes digressive, sometimes repetitive, but always, mutatis mutandis, relevant to our moment.

After I finished re-reading Defoe’s book, some of his sentences from three centuries ago kept ricocheting around my brain. Here is a small selection:

“The Lord Mayor and Sheriffs had made no Provision as Magistrates, for the Regulations which were to be observed; they had gone into no Measures for Relief of the Poor.”

“Many of these were the miserable Objects of Dispair which I have mentioned before, and were remov’d by the Destruction which followed; these might be said to per-ish, not by the Infection it self, but by the Consequence of it; indeed, namely, by Hunger and Distress, and the Want of all Things; being without Lodging, without Money, without Friends, without Means to get their Bread, or without any one to give it them.”

“so now upon this No-tion spreading, (viz.) that the Distemper was not so catching as formerly, and that if it was catch’d, it was not so mortal, and seeing abundance of People who really fell sick, recover again daily; they took to such a preci-pitant Courage, and grew so entirely regardless of them-selves, and of the Infection, that they made no more of the Plague than of an ordinary Fever, nor indeed so much;”

I read Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year on line. There are several paperback editions available. You can probably order one of these through Darvill’s by using the phone or email.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

As with his Moll Flanders and Robinson Crusoe, Defoe is alert to the devices one will rely upon and the lengths one will go to survive. It is no surprise then that long before the plague’s origins and transmission were well understood he shows so well the behaviors a deadly epidemic can generate—flight, denial, evasions, scam promises, quack remedies—then and now on all levels of society and government.

Thanks Jens.

“mutatis mutandis” ..nice.

It seems that at a distance of 400 years the forty year lag and possible fictionalization of his uncle’s account don’t detract, and the obvious scholarship he put into his research make it an intriguing resource today, despite his critics.

It is interesting to note that unlike its two intermediaries, rodent and flea, Yersinia the bacillus was unknown. Robert Hooke published ‘Micrographia’ the year after the London Plague but it took another 200 years and Louis Pasteur for Koch to develop the germ theory of disease [discounting that 11th C. Persian] that made sense of it.

It is also interesting that Plague came to England from China via the Netherlands and was spread despite quarantine and restricted travel, throughout England.. Because no one looked for the vector or protected the vulnerable.

Hmmm.

mutatis mutandis