||| FROM FRASER VALLEY CURRENT ||| Reprint at request of Orcasonian reader

Sumas Lake once covered much of the Fraser Valley’s fertile farmland. This is the story of how it disappeared, how it could re-appear, and some of the challenges ahead.

To understand the flood crisis currently gripping the Sumas Prairie area in eastern Abbotsford, you have to understand the history of the area, and the roles played by the Nooksack River and what was once Sumas Lake. You need to know why Barrowtown Pump Station exists. And you need to know why, if it fails (and maybe even if it doesn’t), the lake will return.

More than eight millennia ago, ice covered the Fraser Valley. But change was in the air and on the ground. The glaciers were melting, and as they receded, they left behind a valley and an early lake between what we now call the Sumas and Vedder mountains. Small watercourses ran along the newly exposed ground of clay and gravel, and silt, feeding a growing lake. The most important of these early watercourses was the Nooksack River, which flowed north from the foothills of Mt. Baker, delivering thick, fertile layers of volcanic sediment.

The lake grew, particularly after the collapse of an ice dam on the Chilliwack River. A short river allowed it to drain into the Fraser River. Spring and fall freshets would send water back into the lake, causing it to expand with the seasons.

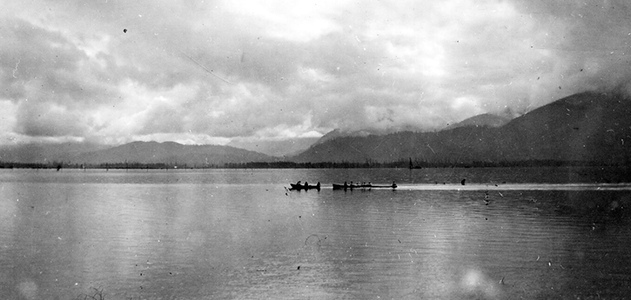

Higher, then lower: the Sumas Lake’s seasonal ebb and flow would play out for thousands of years. The lake expanded when it rained hard—spreading through a wetland ecosystem accustomed to rising water. In doing so, it reduced flooding elsewhere in the region. White sturgeon travelled to the silty lake bed to spawn when the lake was at its lowest. Salmon followed that same path in the fall. The Semá:th people built villages around the lake, following its tides as long ago as 400 BCE.

In one story, shared in A Stó꞉lō-Coast Salish Historical Atlas, a merciless drought left only two survivors: a man and a woman. The pair were separated from each other by great distances, and crawled on their stomachs through the muddy lake floor in search of water. They met at a small pool in the lake basin, and founded the Semá:th people.

“For us, that was our travel routes, that was our economy, that was our food security,” Murray Ned, councillor for the Semá:th First Nation, recently told the Current. “We didn’t have to go too far to access anything else.”

For most of their history, the Semá:th controlled access to the lake, sharing it with other Stó꞉lō communities and the Nooksack nation. When European settlers arrived, they too encountered Sumas Lake. By that time, the Nooksack River no longer flowed north, instead travelling west to the ocean. The lake supported an ecosystem of blueberry bushes, wapato (called an Indian potato by settlers), and blue camas. In 1894, a formidable Fraser River flood covered the valley, and a swollen Sumas Lake extended its shores once again, soaking up water that would have otherwise decimated the new communities.

In a painting of the Sumas valley by American surveyor James Madison Alden, Sumas Lake sits in the background, beyond a line of trees and shrubs.

But the newcomers didn’t like the lake. They hated the mosquitoes. They didn’t use the water. And they were envious of the extremely fertile soil at its bottom.

“The Dominion lands in and around Sumas Lake were useless and unsuited for homesteading,” the Chilliwack Progress reported in November 1912. “The reclamation of these Dominion and private lands would be a great boon to the Fraser Valley and the whole province, not only on account of the large area of now useless Dominion lands that would be rendered fertile and productive, but the enhanced value and usefulness of the still larger area of private lands.”

Sumas Lake, seen here in the bottom right quadrant of an early map, was one of the Lower Mainland’s most prominent geographical features before it was drained 100 years ago. 📷 City Vancouver Archives: AM1594-: MAP 2

So, almost exactly 100 years ago, engineers drained the lake. Or, rather, they pumped water out of the lake, as one must do when a lake bed is lower than all the land surrounding it.)

The engineers created a series of drainage ditches, dredged what we now know as the Vedder Canal to reroute the Chilliwack River, and constructed a large pump station to lift water up and into the Sumas River. That river joined with the Vedder shortly after the pump station, and from there the waters flowed north into the Fraser.

The system was a boon for farmers, but devastated local First Nations.

“They took the lake away and we never got one inch of it,” former Grand Chief Lester Ned told the Vancouver Sun in 2013. (Ned died in October.) “I don’t know how the people survived way back then.”

Despite early problems, the elimination of the lake eventually achieved many of the goals of those who had advocated for the project, providing vast spaces for settlement and farming. When floods happened—like in 1990, when the Nooksack spilled its banks, flowed north to Canada and closed Highway 1—the lake didn’t re-form. That event did briefly remind people of the twin threat posed by an American river and an extinct lake. But not long after the water receded, people’s attention turned elsewhere. Mother Nature had supposedly been tamed.

Barrowtown Pump Station uses four pumps to move water up from Sumas Prairie to the Sumas River. It was built in the 1980s. City of Abbotsford

A problem of nature

The problem then—and the problem now—is physics. Sumas Lake existed for thousands of years the same reason all lakes exist: gravity. When it rained in the Fraser Valley, water ran down the sides of Vedder and Sumas mountains and collected in a shallow basin in the centre of what is now the eastern Sumas Prairie. And when the Fraser rose, it also pushed water into that basin. This was what made Sumas Lake a lake.

The bottom of the lake bed lies roughly at sea level, below the surface level of the nearby Fraser River. Only when enough water fills the prairie to a level equal to the Fraser does the lake begin to naturally empty into that river (via the Sumas River) and then toward the sea. When the Fraser is higher than Sumas Lake (as is the case right now), then water from the Fraser helps fill the lake.

That is how things worked before the lake was drained. For the last century, huge pumps have been responsible for keeping the prairie more or less dry. The original pump station was replaced by the current Barrowtown Pump Station in the 1980s at a cost of $27 million. Today’s facility has four massive pumps to suck water out of the prairie’s fields. On sunny days, only one is needed. Those pumps can usually keep up with the water that flows into the prairie.

But these are not usual days. As we write, late on Tuesday evening, officials say the pump station may soon be swamped with water, forcing the pumps to stop, and for water from the Fraser to begin flowing into the old Sumas Lake bed.

Here we return to the other big cause of much of the flooding being seen on Sumas Prairie: the Nooksack River.

It is the Nooksack’s flood waters that are largely to blame for the current mess that has isolated Chilliwack from Abbotsford and driven thousands from their homes. It’s also the Nooksack’s floodwaters that have swamped the Barrowtown pump station, leading to its possible failure. And yet, many will still not have heard of the Nooksack: a river that runs from the banks of Mount Baker, through northern Washington and empties into Puget Sound without ever crossing into Canadian territory.

READ FULL ARTICLE: https://fvcurrent.com/article/sumas-lake-flooding-history/

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Excellent article.

“The problem then—and the problem now—is physics. Sumas Lake existed for thousands of years the same reason all lakes exist: gravity.”