||| FROM KOMO NEWS |||

After months and months of anticipation, we have officially entered the La Niña climate pattern we’ve been waiting for.

La Niña is the opposing end of the spectrum from El Nino, an oscillation between cooler and warmer than normal waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean that normally completes a full transition, back and forth, every two to seven years. The overall pattern is designated ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillation).

The designation comes as observed water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean finally cooled to levels that met the benchmark set by which past La Niña events were also defined, generally 0.5 degrees Celsius colder than normal.

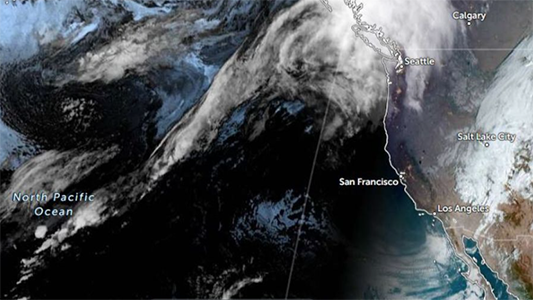

It’s important because abnormally warm or abnormally cold Pacific waters alter the preferred location and intensity of Pacific and Polar jet streams. These rapidly moving currents of air tend to direct storm systems over the U.S. and can be responsible for which areas are wet, which are snowy, which are dry and can even impact temperature patterns.

La Niña conditions, characterized by warmer than normal surface waters of the Equatorial Pacific tend to contribute to a higher likelihood of drier than normal conditions for Southern California. Sadly, Southern California is experiencing very dry conditions with the ongoing fires as Los Angeles has received very little winter rain so far.

For western Washington, La Niña conditions favor wetter and colder winter weather, with snowier mountains.

While we have had several bouts of totally gnarly snowfall over the ski resorts, snowpack depth over much of the Washington Cascades was close to normal Friday, according to SNOTEL telemetry data. However, some specific locations, like Cougar Mountain and Mount Gardener, are far below normal, with only 20-30% of snowpack water equivalent normal.

The last El Nino was declared finished last June, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecasters have been expecting La Nina for months. Its delayed arrival may have been influenced — or masked — by the world’s oceans being much warmer the last few years, said Michelle L’Heureux, head of NOAA’s El Nino team.

“It’s totally not clear why this La Niña is so late to form, and I have no doubt it’s going to be a topic of a lot of research,” L’Heureux said.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**