Book review by Jens Kruse

A little more than a week ago, I reviewed Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map for these pages. It is the story of London’s cholera epidemic of 1854. By examining this outbreak at the microcosmic level of neighborhood and street it gives us an up- close depiction of the spread of cholera and its ravages that also serves as an example of the social, economic, political, medical and public health consequences of the disease.

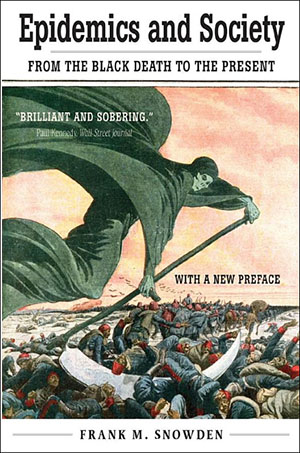

Frank M. Snowden, the Andrew Downey Orrick Professor of History and History of Medicine at Yale University, in his 2019 book Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, does the opposite: he gives us a sweeping overview of the history of epidemics and of their consequences for all aspects of human society from the beginning to the present.

In 22 chapters and roughly 500 text pages he takes us on a tour of the three plague epidemics between 541 and ca.1950, smallpox, yellow fever, dysentery and typhus, cholera, tuberculosis, malaria, polio, HIV/AIDS, SARS and Ebola, and finally, in a preface for the 2020 paperback edition, COVID-19.

In between he gives us a more than 2000 year long history of medicine: from Hippocrates and Galen, from miasma theory to contagionism, from the Paris School of Medicine to the laboratories of Pasteur and Koch, from inoculation to vaccination, from attempts (mostly failed) at eradication, from the practices and institutions of public health to the development of epidemiology.

Throughout, Snowden structures his narrative guided by principles he describes in his “Introduction”:

One of the overall themes structuring Epidemics and Society is an intellectual hypothesis to be tested through the examination of widely dissimilar diseases in different societies over time. This hypothesis is that epidemics are not an esoteric subfield for the interested specialist but instead are a major part of the “big picture” of historical change and development. Infectious diseases, in other words, are as important to understanding societal development as economic crises, wars, revolutions, and demographic change. To examine this idea, I consider the impact of epidemics not only on the lives of individual men and women, but also on religion, the arts, the rise of modern medicine and public health, and intellectual history. (2)

A final important theme of Epidemics and Society is that epidemic diseases are not random events that afflict societies capriciously and without warning. On the contrary, every society produces its own specific vulnerabilities. To study them is to understand that society’s structure, its standard of living, and its political priorities. Epidemic diseases, in that sense, have always been signifiers, and the challenge of medical history is to decipher the meanings embedded in them. (7)

Allow me to give just a few examples of the complex interactions Snowden describes.

When Columbus first landed in 1492 at Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) the island was inhabited by roughly 1,000,000 million indigenous people, the Arawaks. The Spaniards “dispossessed the Arawaks of their territory and enslaved them (102).” They were aided in that process by smallpox and measles, epidemic diseases to which the Arawak lacked all immunity: between 1492 and 1520 the native population was reduced to 15,000. Snowden writes:

Paradoxically, although smallpox and measles thus established the Europeans’ power over the island, the diseases also thwarted the invaders’ original intention of enslaving the indigenous people to work in their plantations and mines. The near-disappearance of the native population drove the Europeans to find an alternative source of labor. (…) In this way disease was an important contributing factor in the development of slavery in the Americas and the establishment of the infamous Middle Passage. (103)

Another example that Snowden discusses is Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. For this purpose Napoleon had assembled the largest military force ever created up to that point, roughly 500,000 men. The conditions of such a large mass of humanity on the march created an ideal environment for various diseases, most importantly dysentery. It spread through the Grande Armée as it marched towards Moscow and killed or incapacitated many of Napoleon’s troops. We do not know exactly how many, but one indicator is that when the Russians finally gave Napoleon the battle he had sought – at Borodino, just outside of Moscow – Napoleon attacked with 134,000 soldiers.

Once Napoleon reached Moscow the Russians had evacuated most of the populations and set fire to the city, so that housing and feeding his occupying troops became very difficult. He was forced to retreat beginning in mid-October and marched back with his remaining troops: harassed by the Russians, weakened by the intensifying winter conditions, and, most of all, by typhus. By the time Napoleon’s once grand army exited Russia it had been reduced to roughly 10,000 men.

The 2014-16 Ebola epidemic in West Africa is an example for the role that environmental degradation can play in the outbreak of disease. The virus that causes Ebola had long been present in fruit bats, but it jumped to humans when the bats – due to deforestation to make room for palm oil plantations – lost their habitat in the canopy of the tropical rain forest and began to feed lower and closer to humans. The epidemic very nearly became a pandemic, but was eventually stopped by an international effort.

Once one has finished reading this book it is instructive to return to the beginning, to the new 2020 preface of the paperback edition. Here are its concluding words:

When COVID-19 began its global spread, it met with success in part because the sentinels had stood down and the world slept. Here the stance taken by the United States is critical: it is the remaining superpower and economic giant; it provides the crucial funds for the efforts of the WHO; and the CDC is the agency that sets the gold standard

for international response. Despite the repeated warnings since 1997, an important driver of present suffering is the position of the American president, who, as the disease spiraled out of control on three continents, asked, “Who would have thought?” A more fitting question is whether, after COVID-19 abates, the world will return to complacency or decide upon a sustainable, long-term assessment of the likely challenges and organize the means to meet them. Scientific research, enhanced healthcare infrastructures, close international collaboration, health education, protection of biodiversity, and ample funding will all need to be deployed around the globe if we are to secure our civilization. (xi-xii)

Frank M. Snowden’s Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2020) can be checked out from the Orcas Library or obtained through Darvill’s Bookstore.

Thanks for publishing this review. This timely, historical account may help develop perspective and provide an understanding of some of the long-term societal impacts of Covid-19.

“‘Spillover” by David Quammen, is also excellent, and covers not only SARS, but Ebola, HIV, malaria, Nipah and Q-fever. The central thesis is rhat global deforestation and development is breaching natural barriers.between humans and endemic zoonotic viruses in other mammalian species, notably bats.

Thank-you, Jens.

It will take all of humanity to stand together to adapt to the current pandemic. Since our president is unable to lead an effective response and since social media are so efficient at spreading counterproductive narratives, “influencers” from all social groups must be convinced to step up and advocate for responsible behaviors including wearing cloth face coverings in public, social distancing, and support for widespread testing for the virus that causes Covid-19. People without symptoms need to be tested as well as people with symptoms because this virus is a stealth agent. When it infects, it can cause a range of symptoms from no symptoms to severe illness. Even if tests are not perfectly accurate, it is the frequency of the testing that matters. We need easily-used home tests that can give a rapid result. Self-testing at home would help address the shortage of personal protective equipment that continues to plague us.

Thanks, Janet. With respect to simple at home tests there was this in the NYTimes about a week ago

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/03/opinion/coronavirus-tests.html?searchResultPosition=2