Historically, an overhaul for humanity’s energy system would take hundreds or many thousands of years. The rapid shift to cleaner, more sustainable sources of power generations will easily be the most ambitious enterprise our species has ever undertaken.

||| FROM COMMON DREAMS.ORG

Humanity’s transition from relying overwhelmingly on fossil fuels to instead using alternative low-carbon energy sources is sometimes said to be unstoppable and exponential. A boosterish attitude on the part of many renewable energy advocates is understandable: overcoming people’s climate despair and sowing confidence could help muster the needed groundswell of motivation to end our collective fossil fuel dependency. But occasionally a reality check is in order.

The reality is that energy transitions are a big deal, and they typically take centuries to unfold. Historically, they’ve been transformative for societies—whether we’re speaking of humanity’s taming of fire hundreds of thousands of years ago, the agricultural revolution 10,000 years ago, or our adoption of fossil fuels starting roughly 200 years ago. Given (1) the current size of the human population (there are eight times as many of us alive today as there were in 1820, when the fossil fuel energy transition was getting underway), (2) the vast scale of the global economy, and (3) the unprecedented speed with which the transition will have to be made in order to avert catastrophic climate change, a rapid renewable energy transition is easily the most ambitious enterprise our species has ever undertaken.

As we’ll see, the evidence shows that the transition is still in its earliest stages, and at the current rate, it will fail to avert a climate catastrophe in which an unimaginable number of people will either die or be forced to migrate, with most ecosystems transformed beyond recognition.

Implementing these seven steps will change everything. The result will be a world that’s less crowded, one where nature is recovering rather than retreating, and one in which people are healthier (because they’re not soaked in pollution) and happier.

We’ll unpack the reasons why the transition is currently such an uphill slog. Then, crucially, we’ll explore what a real energy transition would look like, and how to make it happen.

Why This Is (So Far) Not a Real Transition

Despite trillions of dollars having been spent on renewable energy infrastructure, carbon emissions are still increasing, not decreasing, and the share of world energy coming from fossil fuels is only slightly less today than it was 20 years ago. In 2024, the world is using more oil, coal, and natural gas than it did in 2023.

While the U.S. and many European nations have seen a declining share of their electricity production coming from coal, the continuing global growth in fossil fuel usage and CO2 emissions overshadows any cause for celebration.

Why is the rapid deployment of renewable energy not resulting in declining fossil fuel usage? The main culprit is economic growth, which consumes more energy and materials. So far, the amount of annual growth in the world’s energy usage has exceeded the amount of energy added each year from new solar panels and wind turbines. Fossil fuels have supplied the difference.

So, for the time being at least, we are not experiencing a real energy transition. All that humanity is doing is adding energy from renewable sources to the growing amount of energy it derives from fossil fuels. The much-touted energy transition could, if somewhat cynically, be described as just an aspirational grail.

How long would it take for humanity to fully replace fossil fuels with renewable energy sources, accounting for both the current growth trajectory of solar and wind power, and also the continued expansion of the global economy at the recent rate of 3 percent per year? Economic models suggest the world could obtain most of its electricity from renewables by 2060 (though many nations are not on a path to reach even this modest marker). However, electricity represents only about 20 percent of the world’s final energy usage; transitioning the other 80 percent of energy usage would take longer—likely many decades.

However, to avert catastrophic climate change, the global scientific community says we need to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050—i.e., in just 25 years. Since it seems physically impossible to get all of our energy from renewables that soon while still growing the economy at recent rates, the IPCC (the international agency tasked with studying climate change and its possible remedies) assumes that humanity will somehow adopt carbon capture and sequestration technologies at scale—including technologies that have been shown not to work—even though there is no existing way of paying for this vast industrial build-out. This wishful thinking on the part of the IPCC is surely proof that the energy transition is not happening at sufficient speed.

Why isn’t it? One reason is that governments, businesses, and an awful lot of regular folks are clinging to an unrealistic goal for the transition. Another reason is that there is insufficient tactical and strategic global management of the overall effort. We’ll address these problems separately, and in the process uncover what it would take to nurture a true energy transition.

The Core of the Transition is Using Less Energy

At the heart of most discussions about the energy transition lie two enormous assumptions: that the transition will leave us with a global industrial economy similar to today’s in terms of its scale and services, and that this future renewable-energy economy will continue to grow, as the fossil-fueled economy has done in recent decades. But both of these assumptions are unrealistic. They flow from a largely unstated goal: we want the energy transition to be completely painless, with no sacrifice of profit or convenience. That goal is understandable, since it would presumably be easier to enlist the public, governments, and businesses in an enormous new task if no cost is incurred (though the history of overwhelming societal effort and sacrifice during wartime might lead us to question that presumption).

But the energy transition will undoubtedly entail costs. Aside from tens of trillions of dollars in required monetary investment, the energy transition will itself require energy—lots of it. It will take energy to build solar panels, wind turbines, heat pumps, electric vehicles, electric farm machinery, zero-carbon aircraft, batteries, and the rest of the vast panoply of devices that would be required to operate an electrified global industrial economy at current scale.

In the early stages of the transition, most of that energy for building new low-carbon infrastructure will have to come from fossil fuels, since those fuels still supply over 80 percent of world energy (bootstrapping the transition—using only renewable energy to build transition-related machinery—would take far too long). So, the transition itself, especially if undertaken quickly, will entail a large pulse of carbon emissions. Teams of scientists have been seeking to estimate the size of that pulse; one group suggests that transition-related emissions will be substantial, ranging from 70 to 395 billion metric tons of CO2 “with a cross-scenario average of 195 GtCO2”—the equivalent of more than five years’ worth of global carbon CO2 emissions at current rates. The only ways to minimize these transition-related emissions would be, first, to aim to build a substantially smaller global energy system than the one we are trying to replace; and second, to significantly reduce energy usage for non-transition-related purposes—including transportation and manufacturing, cornerstones of our current economy—during the transition.

In addition to energy, the transition will require materials. While our current fossil-fuel energy regime extracts billions of tons of coal, oil, and gas, plus much smaller amounts of iron, bauxite, and other ores for making drills, pipelines, pumps, and other related equipment, the construction of renewable energy infrastructure at commensurate scale would require far larger quantities of non-fuel raw materials—including copper, iron, aluminum, lithium, iridium, gallium, sand, and rare earth elements.

While some estimates suggest that global reserves of these elements are sufficient for the initial build-out of renewable-energy infrastructure at scale, there are still two big challenges. First: obtaining these materials will require greatly expanding extractive industries along with their supply chains. These industries are inherently polluting, and they inevitably degrade land. For example, to produce one ton of copper ore, over 125 tons of rock and soil must be displaced. The rock-to-metal ratio is even worse for some other ores. Mining operations often take place on Indigenous peoples’ lands and the tailings from those operations often pollute rivers and streams. Non-human species and communities in the global South are already traumatized by land degradation and toxification; greatly expanding resource extraction—including deep-sea mining—would only deepen and multiply the wounds.

The second materials challenge: renewable energy infrastructure will have to be replaced periodically—every 25 to 50 years. Even if Earth’s minerals are sufficient for the first full-scale build-out of panels, turbines, and batteries, will limited mineral abundance permit continual replacements? Transition advocates say that we can avoid depleting the planet’s ores by recycling minerals and metals after constructing the first iteration of solar-and-wind technology. However, recycling is never complete, with some materials degraded in the process. One analysis suggests recycling would only buy a couple of centuries’ worth of time before depletion would bring an end to the regime of replaceable renewable-energy machines—and that’s assuming a widespread, coordinated implementation of recycling on an unprecedented scale. Again, the only real long-term solution is to aim for a much smaller global energy system.

The transition of society from fossil fuel dependency to reliance on low-carbon energy sources will be impossible to achieve without also reducing overall energy usage substantially and maintaining this lower rate of energy usage indefinitely. This transition isn’t just about building lots of solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries. It is about organizing society differently so that is uses much less energy and gets whatever energy it uses from sources that can be sustained over the long run.

How We Could Actually Do It, In Seven Concurrent Steps

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Lin, thank you for sharing this article–An important global perspective, also relevant at the level of local and personal energy use, with positive solutions. But, given that the US is not even a signatory to the the Paris Climate Accords, and that the proposed solutions call for a total revision of our national and global economic approach, the tiny steps we’re taking toward green energy at present seem to be little more than tilting at wind (or tidal) turbines.

Heinberg’s piece above points out a deeply painful reality: “So far, the amount of annual growth in the world’s energy usage has exceeded the amount of energy added each year from new solar panels and wind turbines. Fossil fuels have supplied the difference.”

In other words: Despite all the PV, wind turbines, etc. that have been built and installed, worldwide fossil fuel consumption is greater in 2024 than ever before. We are not only not improving the predicament, we’re making it worse!

Unfortunately, Heinberg’s “7 Steps…” response to this ever deeper grave we are digging ourselves are almost all non-feasible. The only “step” I see as actually plausible is global population decline, and barring massively catastrophic death tolls, that cannot come soon enough to avoid kicking our planetary climate into new, unknown and unknowable patterns.

I think it is about time to prioritize ADAPTATION and MITIGATION to climate change. Even if we ceased the burning of fossil fuels completely tomorrow, the amount of global heating that is already “baked in” will continue to cause serious changes in weather patterns for centuries. At this point there is no going back to the relatively stable climate of the Holocene. We are in for new territory, climate-wise, and we would be wise to start preparing for the worst, rather than buying more PV panels and hoping for the best.

There is a storm on the horizon and we had best batten down the hatches and reef the sails before it hits in earnest.

Not just new climate territory… we’ve poisoned the entire planet, destroyed huge swathes of habitat, decimated 70% of wildlife in just the past 50 years, and caused the sixth mass extinction. Efficiency and solar panels will not make even a tiny dent in the storm that’s on the horizon for us (and already here for many others); indeed, more solar panels will make it worse (after all, making solar panels requires destroying more habitat, thus exacerbating the sixth mass extinction).

I 100% agree we need to prepare for what’s coming, but as I’ve discovered, most are unwilling to even discuss ecological overshoot, much less prepare for the inevitable results. A grand total of 4 people from the county attended my series last year on ecological overshoot (although many others from around the world did). I think that illustrates the extraordinary level of dissociation from reality we’re facing here.

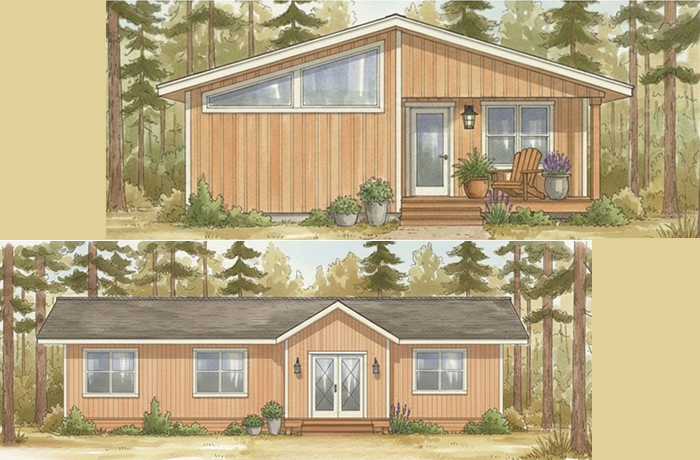

OPALCO has some great ways that you can save money and add energy efficiency to your home. Check out our Energy Savings Hub: https://www.opalco.com/energy-savings-hub/.

Good plan, Krista! Like any investment it costs, but in this case the savings to the budget and to the planet keep coming and coming.

When Bruce Anderson and I published “The Solar Home Book” way back in the mid-1970s, we urged readers not to spend a dime on solar energy unless they’d first spent a dollar on energy efficiency. That advice remains true today, despite the great advances in photovoltaics that have occurred since then. Especially here in the PNW, where the sun doesn’t shine very much in winter, when you need it most.

Along with the important ideas of all replies above, I feel that one of the more important things to be done has been left out. There are way too many people on earth

using up all that earth has supplied us to get by. The population must decline, but there seems to be many who don’t understand that. The ones who are trying to tell women what they can and can’t do with their bodies. They want all they can get for more votes! Please remember that when you vote!!

We’re facing what can only be described as the classical term, “interesting times.” Our social security system, probably like that of many other nations, is not a savings account, it is a Ponzi scheme, funded by those working to pay for those retired. It works only so long as enough people contribute to those then in retirement. As retirees live longer, the years of work for those not yet retired have to be lengthened. This was done once and will probably happen again in a few years. At the same time, as the world population levels off, the number of workers whose social security taxes pay current retirees, will diminish, but even if they don’t, our retirement Ponzi scheme requires a constantly increasing number of workers or it has to collapse.

Our thinking needs to broaden. We cannot only look at one piece of the problem at a time.