Twenty years in active service, and always a Marine

— by Margie Doyle —

John Erly was a bright-eyed teenager living in Seattle who enlisted in the U.S. Marines because he wanted to live on a warm sunny beach like movie star John Wayne. At 18 years old, he thought, “no more snow.”

That was in 1951 and his first tour was in the Korean War, where the temperatures were 40 degrees below. He was assigned to a psychological warfare team, who set up speakers broadcasting propaganda to their Korean counterparts, “who were doing the same to us,“ says Erly.

He spent 13 months there, living in tents when they were available, sleeping on the ground when they weren’t. The worst aspect of it, he says, was the cold, but “when you’re that age — being young, with other people, enjoying camaraderie — it’s fun. The Marines built that sense into you in boot camp.”

He returned to the U.S. to San Francisco, and found that “people didn’t admire what we were doing; it was unpopular. I didn’t hear ‘Thank you for your service,’ until maybe 10 years ago.”

He recalls being dressed in his formal uniform and people spitting at him. “I was all pumped up from World War II — that’s all we knew; we wanted to be heroes when we came home.”

He felt the same reaction when he was sent to Tacoma as a recruiter for the reserve unit that had been sent to Korea. “Maybe it was how the City of Tacoma felt about what happened to their reserve unit,” whom Erly surmised had seen action in Korea.

“It was a different time then: no drugs; no booze, except maybe the occasional beer. It was just a different time.”

Three years later, his next assignment during the Cold War was assembling nuclear warheads on missiles in the California desert, at Twenty-nine Palms. The arms were never used as a nuclear weapon.

Then his ability to train and motivate others was used as a Drill Instructor, after a training course that weeded out half of the Drill Instructor candidates. “At that time, Drill Instructors were considered the elite of the Marines,” Erly says. The hardest part of his job then, was to “instill discipline. There were thugs, mama’s boys and juvenile delinquents, and the occasional pro football player. You learned to be a Marine 24 hours a day.

“And at the time, there was still no drugs.”

Then he became a teacher at the Drill Instructor school. His wasn’t a career where he set a course and campaigned to follow it. Rather, he went where he was sent, including the day he was told to put on his dress uniform and report to his commanding general’s office.

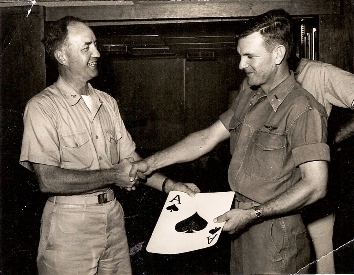

There, to his surprise, he was promoted from an enlisted man to an officer. Thanks to a recommendation (he never knew from whom) he became a 2nd Lieutenant—“with no Officer Candidate School, no training.”

“Very few enlisted men get commissioned – they called us Mustangs.” There was a big jump in pay and opportunities became available that were not open to enlisted men, but basically, his life remained the same, Erly says. “When I was off duty, I went home” to wife Marilyn and daughters Tricia and Robin.

Those opportunities included assignments at the school for aerial observers, and then a position as instructor, including three or four trips to Vietnam for different assignments. During the Vietnam War, he served as the commanding officer for a Marine detachment on a cruiser. He explains, “On a cruiser, the Marines man the guns; so he was directing the men in his own detachment. He also flew with the Korean Marines, directing naval gunfire.

His memories of that war are different from the drug-induced “Fog of War” he hears many recall. “I may have been blind, but I don’t recall the drug use.” He had friends in the Army infantry and their recollections match his. He says, “I’m aghast at how many people, that’s all they remember.”

Though he had achieved a lot, Erly didn’t get a big head: “I felt so fortunate. The biggest thrill was seeing my girls; they loved to go through the gate, where they were always saluted.”

Then there was the round-the-world trip through the Suez Canal to Europe. Among the places he visited were Hawaii, Japn, Okinawa, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Panama, Italy , France, Greece and Malta.

He recalls the romance of travel, with “Marilyn and the girls following along,” Erly said.

Still, “when you’re an enlisted man, and then you’re commissioned, you’re in a different group.” His friend, a general, told Erly that he’d never make general because he didn’t know how to answer questions – “you don’t b.s.” Erly knew it was the truth, and that he’d had “a pretty good career.”

He looked at the pay, the possibility of a second career and the increased opportunities to be at home and retired to work at an insurance company in San Diego, first as an agent, then as a manager. He moved to Washington state, after 23 years, and eventually moved to Orcas and began his real estate career.

With his family living in the Victorian farmhouse on North Beach Road, he rented a desk at Cherie Lindholm’s real estate office, and “next thing I know, I’ve been there 20 years!”

“The biggest thing about being a veteran that I appreciate today – with titanium knees, two bypasses and shoulder surgeries – is the medical benefits.”

Erly says, “There have been days, but I’m lucky. I’ve always had jobs I liked.”

He enjoys Chritsmas vacations in Hawaii, but says he doesn’t know how to relax, one of my failings.” Still, most days he’ll be at his office in Eastsound, most evenings at home, maybe watching PBS News or Masterpiece Theater.

At 80 years old, he says, “I’m looking forward to being 100. “I’ll probably be doing real estate on Orcas till I die – you meet nice people. You might not socialize with everybody, or have to apologize for something you’ve said, but you’d be hard-pressed to find somebody you don’t like here.

“As long as my girls are here, there’s no place I’m going.”

Semper Fi, dear John! You’re the best!

Thank you for your service John.

Glad to see you “young fellers” get the recognition you deserve. Veterans Day always brings a lot of great memories. And too many not so great. Keep the faith, John.

Proud to know you John Erly!

Thank you for your presentation to the students of Orcas Christian School, and for the service to your country and fellow Marines. God Bless and Keep you.

Thank you Margie for recognizing an important member of our community and a good man, our friend John Erly. K&K