||| FROM RUSSEL BARSH for KWIAHT |||

An exploratory study by the nonprofit conservation laboratory Kwiaht has discovered that ticks are widespread in the San Juan Islands, but not yet a significant threat to human health or wildlife.

Funded in part by the San Juan Island Community Foundation, the 10-month study was based mainly on ticks found by islanders on themselves, or on their pets. All ticks collected from islanders were screened genetically for eight tick-borne bacterial pathogens including Borrelia, which causes Lyme Disease. Genetic screening was conducted by the Pennsylvania Tick Research Laboratory, which has extensive experience testing ticks for East Coast health departments. No comparable public program exists in Washington State.

Kwiaht scientists also received ticks from Wolf Hollow Wildlife Rehabilitation Center and checked wildlife in San Juan Island National Park for ticks during routine ecosystem surveys that often encounter reptiles and small mammals. “One of our most exciting finds was a young female Alligator Lizard with four ticks,” says project coordinator Russel Barsh. “Based on the amount of blood the ticks had consumed, we learned that the host lizard had picked them up over a period of four days.” Alligator Lizards are reportedly a reservoir of ticks in the Gulf Islands, but their role in tick ecology in the San Juan Islands remains unclear.

Other ticks processed thus far were found on people, dogs, cats, deer, and a fox, and were collected on Cypress, Lopez, Orcas, San Juan, Waldron islands. Most were encountered in semi-rural residential areas, including backyards and parks, mainly shrubby rather than grassy.

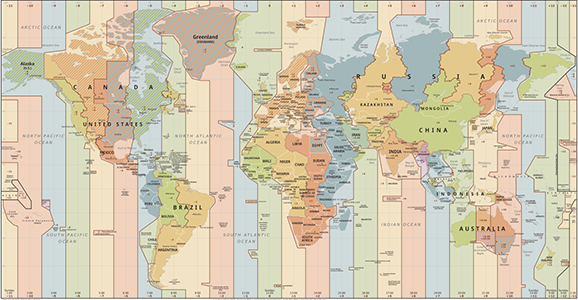

Significantly, two of the three species of ticks recovered from people, pets, and wildlife in the San Juan Islands are non-native, originating east of the Rocky Mountains. “We presume they were introduced to the islands by unwitting hikers and dog-owners,” Barsh says. “Once attached, a tick can feed for several days before dropping from its host, and can remain lively for a week or longer in clothing or sleeping bags.” A person with a pet can drive across the country in that time.

“There’s more to learn, and we should continue monitoring for the first signs of Lyme or other tick-borne diseases in the islands because we attract so many visitors from states where tick-borne diseases are well established,” Barsh says. Hikers, picnickers, pet-owners, hunters and farmers are urged to check for ticks, and submit any they find to Kwiaht for testing.

Ticks can be kept in a dry plastic sandwich bag or envelope, and mailed to Kwiaht, PO Box 415, Lopez Island, WA 98261. Include information on when and where the tick was found, and on what host, and a phone or email address where you can receive the results of testing.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

“All ticks collected from islanders were screened genetically for eight tick-borne bacterial pathogens including Borrelia, ” And WHAT were the results of the testing? Kind of an important point to leave out, don’t you think?

Ken, they all tested negative for all of them.

I found three on my dog last week. Two looked exactly like the photo above with the engorged belly. I will be sure to save any more I find and send them your way.

I still have bad memories of living in a high Lyme tick area near Philadelphia. My father and father-in-law both got Lyme from tick bites, and both suffered significantly. Finding a Lyme tick embedded in your skin was the beginning of several days of worry until the telltale “bullseye” appeared, ir it didn’t and you were safe, until the next bite.

Walking in the woods, which had been a joy all my life, became risky, not just because of poison ivy, for which I was always on the lookout. Lyme ticks are essentially invisible. So this meant stuffing pant legs down socks, checking one’s body carefully after a hike, and for some people, using repellent sprays and lotions.

Then there were the pets. Dogs especially would pick them up and the ticks would end up on my children or myself.

I know this sounds a bit negative, but there is truly nothing good about Lyme ticks! Whatever can be done to keep them from “here” would be a good thing. We’ve worried so much about “other” people bringing Covid to the islands. This will sound harsh but I predict Lyme ticks will arrive here on visiting canines. Folks love their pets as children but take it from someone who’s seen too many folks suffer from Lyme, and you might agree that a careful stance might need to be taken with animals coming and going.

I appreciate Russel’s attention to this potential menace! Thanks.

What kinds of ticks were identified?

Barbara, the three species we received samples of are Ixodes pacificus, I. scapularis, and Dermacentor variabilis.

Thank you, Russel and Madronna for again being ahead of the curve on this. About 2 years ago now, I shipped a tick from my cat to them for free ID-ing. It was a Lyme bearing tick, but didn’t harbor the disease.