||| FROM WASHINGTON POST |||

In the early 19th century, British people finally had access to the first vaccine in history, one that promised to protect them from smallpox, among the deadliest diseases of the era. Many Britons were skeptical of the vaccine, however, with fears extending well beyond the fatigue and sore arm that go along with many modern shots. The side effects they dreaded were far more terrifying: blindness, deafness, ulcers, a gruesome skin condition called “cowpox mange” — even sprouting hoofs and horns.

With that, the world’s first anti-vaccination movement was born.

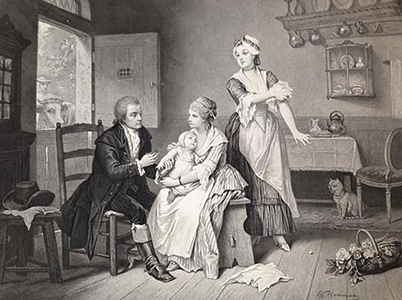

As history tells it, young Edward Jenner heard a milkmaid brag that having cowpox made her immune to smallpox. And years later, as a doctor, he drew matter from a cowpox pustule on the arm of a milkmaid to vaccinate a young test subject (depicted in the drawing above).

Just as quickly as doctors heralded Edward Jenner’s revolutionary 1796 discovery that the deadly smallpox virus could be prevented with a cowpox vaccine, some Brits met the news with a superstitious distrust that bordered on hysteria. Opposition to vaccination would grow and evolve over the next 100 years to become one of the largest mass movements of 19th-century Britain. People refused the vaccine for medical, religious and even political reasons — plunging the nation into a debate that would rage for generations and foreshadow current coronavirus vaccine conspiracy theories.

“It was an enormous mass movement, and it built on many traditions, intellectual and otherwise, about liberty,” said Frank Snowden, a historian of medicine at Yale University. “There was a rejection of vaccination on political grounds that was widely considered as another form of tyranny.”

Yet Britons had been living under a viral tyranny for much longer. By the turn of the 19th century, smallpox had ravaged much of the world. In Europe, some 400,000 people were believed to die annually from the disease. Those who did survive were often permanently disfigured.

An illustration shows Edward Jenner performing his first vaccination on James Phipps, age 8, on May 14, 1796. (Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

The turning point came — or at least ought to have come — when Jenner discovered that dairymaids were often protected from smallpox because of their exposure to the less-dangerous cowpox. He conducted an experiment to test his hypothesis that exposure to this similar disease might protect others from smallpox. He extracted pus from a woman infected with cowpox, injected it into a healthy boy and exposed him to smallpox. The child did not become ill. Similar experiments bore out the same results.

Jenner and his supporters heralded this discovery for the deliverance that it was. Politicians, fellow doctors and major thinkers of the day rejoiced. The writer Robert Bloomfield penned a poem in praise of Jenner, calling his discovery a “blessing.”

At the same time, some members of the general populace — along with several prominent doctors — were skeptical of the idea of being injected with a disease, especially a disease originating with a farm animal. Nineteenth-century Britain was a deeply religious society, and some condemned vaccination as a violation of humans’ God-given healing abilities.

“One can see it in biblical terms as human beings created in the image of God, and therefore being supreme,” Snowden said. “The vaccination movement injecting into human bodies this material from an inferior animal was seen as irreligious, blasphemous and medically wrong.”

Fiery pamphlets, lectures and caricatures tipped off a war of the words that would galvanize huge numbers of Brits into the anti-vaccination movement. In an 1805 pamphlet, William Rowley, a member of the Royal College of Physicians, warned against vaccination, threatening the direst possible side effects. Rowley (among others) went so far as to suggest that the injection of cow material into a human body could cause a person to begin to resemble a cow, sprouting actual horns out of his head and hoofs in place of feet. Even those who could not read would have easily understood the color engravings of an ox-faced boy with an enormous red lump hanging off his cheek, or a child covered in open abscesses.

Featured image above: “Vaccinae vindicia; or, defence of vaccination,” an 1806 work from English physician Robert John Thornton, included this illustration of the theories of Benjamin Moseley, a vaccination critic who suggested that cowpox injections might lead women to have sex with bulls and produce half-cow offspring. (Wellcome Collection/Public Domain)

READ FULL ARTICLE: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/11/14/smallpox-anti-vaccine-england-jenner/

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

And now smallpox has been eradicated worldwide because of vaccination!