— by Cara Russell —

Orcas High School Teachers Val Hellar and Kathy Collister have been managing the senior projects at OHS for the last decade, and both have seen some “interesting” projects for even longer.

“Remember the student who put a motor on a barcalounger, and then drove it through the high school parking lot?” Collister reminded Hellar. “He did it just because it could be done.”

Orcas High School had incorporated the requirement for a Senior Project In obtaining a High School Diploma before the State of Washington Legislature mandated completion of a ‘Culminating project’ as a prerequisite for a Washington State diploma (Note: the 2014 legislature removed this requirement).

According to State of Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, each school district may determine their own guidelines for the Senior Project, which:

• encourage students to think analytically, logically and creatively and to integrate experience and knowledge to solve problems.

• give students a chance to explore a topic in which they have a great interest.

• offer students an opportunity to apply their learning in a “real world” way.

Senior projects were started at OHS when teacher Kristine McLane introduced the concept in 1995. Hellar said, “We are evolving the process — next year will be the 20th year that OHS has involved Senior Project with the graduating process.”

OHS graduates who complete Senior Projects have found the entire process to be quite valuable: choosing what to investigate; experiencing practical applications of their learning; serving the public with their time and effort; working with a mentor in school or in the community; demonstrating what has been learned.

As part of the Senior Project, each student is expected to demonstrate essential skills through reading, writing, speaking, production and/or performance. In addition to the demonstration aspect of the project, the Senior is required to write a research paper (not necessarily related to their project.) “We found that we were creating wild stretches to try and make them connected to the project,” said Collister. The paper must pose a question and demonstrate a solution or an answer.

The project must be presented to a community or peer panel, along with a portfolio of work and/or a multimedia presentation

OASIS kids also have to do it as well, but no paper is required. It’s stressful, these requirements, they cannot participate in the graduation ceremony. The paper is not required by the state, but the project is.

The students are to demonstrate a minimum of 30 hours’ worth of work. Usually the first semester is dedicated to writing the paper and the second semester is focused on the practical aspects of the project. The paper at the end of the fall semester must be 8-10 pages long, and include 10 scholarly resources.

The good projects take a lot longer than the required 30 hours, and are easy to tell apart from the others in the quality of the work, the teachers said.

Students gain important skills such as leadership, project- and time-management public speaking; all of which require self-motivation adn persistence.

And by the time the students graduate, they have produced a scholarly paper, and demonstrated their acquired knowledge.

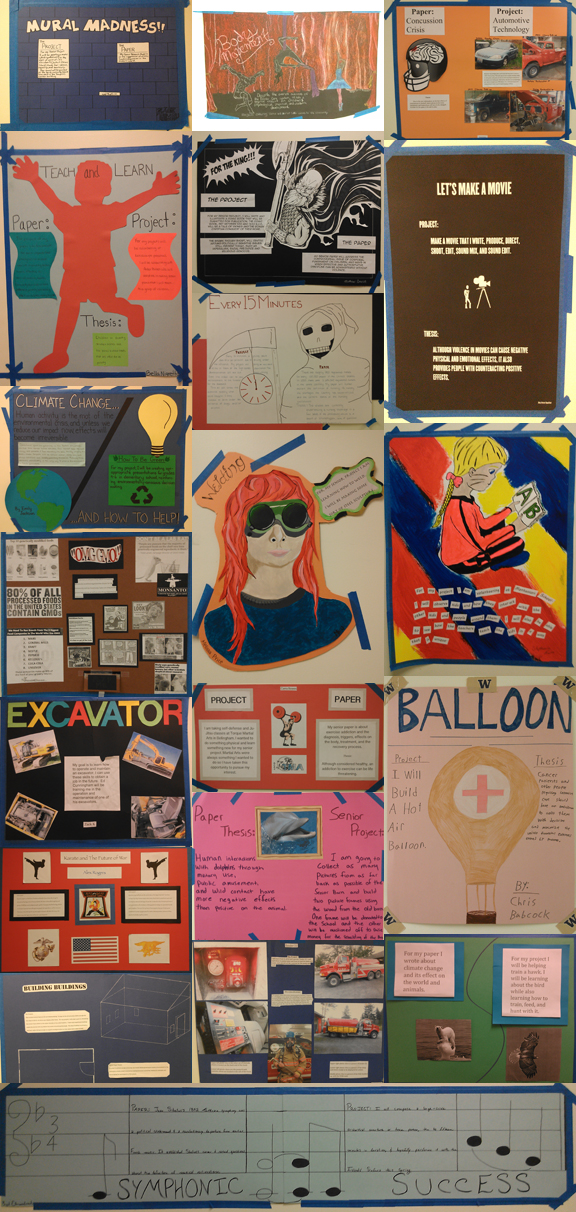

Projects include the manufacture of items such as:

- an American Indian style teepee

- a musical instrument

- refurbishing boats

- converting a car engine to biodiesel fuel

- building projects such as climbing apparatus, chicken sheds and decks

Service projects, helping in efforts such as:

- local museums

- Haitian hurricane rebuilding

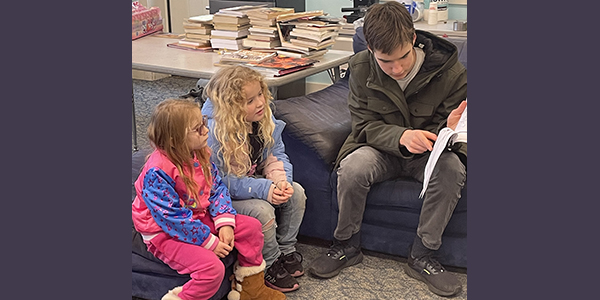

- teaching

- recycling and environmental projects

Some project ideas have met with a resounding “no” from teachers:

- Skydiving

- Tattoo projects

- Teaching a raven how to talk

- Observing public reactions to the disabled in a mall

“Disasters could result,” said Hellar. “When you have a project that relies on other people to participate, a lot of the time those people don’t show up. Sometimes when they don’t work very well, that can be useful, and the students can learn from that.” Students may learn by working on their senior project that it is not something they want to pursue after all.

There have been projects over the years that have left an impact of Hellar and Collister, such as a student-produced video on the process of death and dying. “The subject matter really got to me,” said Hellar.

She mentioned another senior project where the student who created a documentary film interviewing veterans of war.

“Another student made a beautiful dulcimer,” said Collister.

Nonprofits welcome the inquisitive student in, and would like to see more students get involved in their organizations. Some Island businesses and agencies have taught students in the past how to work a back hoe, knit or sew, record music, build boats.

“The seniors couldn’t do their projects without people giving of their time,” said Hellar.

This year, on Tuesday June 10, the seniors will present their projects to the public. The community is welcome to attend.

In the meantime, if a senior comes calling on you, please consider your value as a resource to them in fulfilling this important part of their Orcas public school education.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

It’s great to see that the original projects are still intact. Our good friend, Kristine McLane will enjoy reading the article.