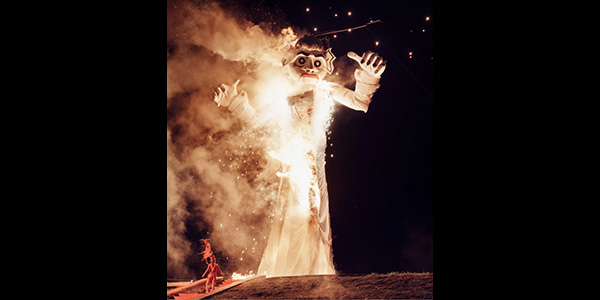

Every year, Santa Fe incinerates a giant puppet of Zozobra — a ritual meant to purge anxiety and promote a reset.

||| FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES |||

For most of the millions of travelers who make the trek each year, there is no reason to go to Santa Fe except to go to Santa Fe. Just about everything that needs doing can and should be done somewhere else, someplace easier to get to than this tiny city 7,000 feet in the air, whose airport terminal is a fraction of the size of a typical American grocery store. But this town of 90,000 residents strives to ensure that its singularity is reason enough.

Which makes it remarkable that Santa Fe’s most distinctive motif is left inscrutable to outsiders. A towering ghoul points down from a mural on one of the city’s busiest streets with no context. At a local confectionery, a scowling white figure in a cummerbund is rendered in chocolate — why? Even if you clock that the big-eared goblin tattooed on the biceps of a local electrician is the same creature depicted (being consumed by flames) on the cab of a municipal fire truck, you will encounter nowhere an explanation of who or what this monster is — unless you happen to be in Santa Fe on the one evening a year when locals construct a building-size version of this thing and set it on fire.

The explanation is a touch nonsensical: This is Zozobra, a beast who lives in the mountains nearby. The people of Santa Fe invite him into town every year on the pretext of a party in his honor. He arrives at the party dressed in formal attire, thrusts the town into darkness and takes away “the hopes and dreams of Santa Fe’s children,” whom he also kidnaps. The townspeople try and fail to subdue him with torches. But then the Fire Spirit, summoned by an atmosphere of cooperation among the town’s citizens, appears and, flying high off the good vibes, battles Zozobra until he is consumed by fire.

If you are fortunate enough to be around on the exactly right night in late summer — the Friday before Labor Day — you may find yourself surrounded by, and even join in with, the screaming citizens of Santa Fe as they string up this enormous, writhing pale-faced humanoid on a pole on a hill overlooking their homes and burn him while he moans until dead.

“Burn him!” demand the children onstage. “BUUUURN HIIIIIM!” roar the adults from the crowd, a portion of whom are inebriated. Unseen, a local judge howls into a microphone, providing the voice of a gargantuan puppet being cooked alive. It is possible that, one century ago, the forebears of the current population discovered the violent secret to happiness in their high, dry town — and that it is annual, ritualized killing by flames. Just in case that’s right — in fact, proceeding on an assumption that it is — the local citizenry have recommitted the monstrous puppet’s murder every year for 100 years straight, so far. The aim is to incinerate their gloom.

The beast’s name, plucked from a Spanish-language dictionary, derives from the verb “to capsize.” As a noun, zozobra, it conveys a poetic second meaning: “anxiety,” or becoming shipwrecked in a sea of one’s own thoughts. In 2024, of course, this prospect sounds like an indulgence; people pay $100 an hour to do that. These days, we are less likely to become lost in an ocean of our own ruminations than in a whirlpool of alien flotsam: text that resembles news but isn’t; images that resemble photographs but aren’t; and, perhaps most profuse, random strangers’ opinions, once a niche resource rarely obtained except by those who sought it, now an omnipresent element of life. If anxiety is defined by obsessive thoughts, the constant pointless playing out of disastrous scenarios, it is no wonder our age feels excessively anxious: We invite these into our minds constantly.

It is a comforting thought that the burning of a puppet could do away with any one person’s problems, to say nothing of an entire city’s — or country’s. Anxiety has a strong anticipatory element: It is predicated on what might happen, what could go wrong. Once a specific future snaps into place, it survives only by attaching to a new object of rumination. Why not incinerate it before it can spread?

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Maybe we should do the same here on Orcas, even if it’s “only” symbolic.