The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History

— by Jens Kruse —

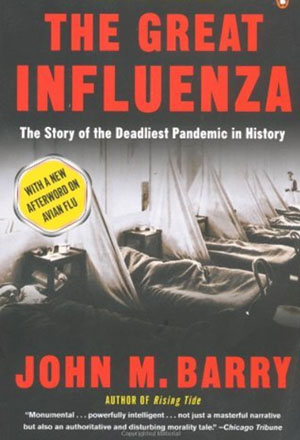

John Barry, the author of, among other books, Rising Tide: the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How it Changed America, first published The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History in 2004.

I recently read it in a paperback edition published in 2018, 100

years after the 1918 influenza pandemic. In the “Afterword” to that edition, Barry warns of pandemics to come and tries to learn the lessons of the 1918 pandemic. He states: “For if there is a single dominant lesson from 1918, it’s that governments need to tell the truth in a crisis”(460).

We will return to that “Afterword” later, but meanwhile I will try to

describe this monumental and authoritative account. It is not just a

narrative of the pandemic, i.e. medical and epidemiological history, but

also a social, political, economic, and military history of the United States

during the years of the pandemic.

In 36 chapters organized into 10 sections he describes how a small group of men and women and a few institutions transformed the pitiful state of American medical care in the late 19th and early 20th century into something more professional, scientific, and robust, something that could compare to medical care and medical science in the most advanced European countries. He explains how viruses and bacteria function to become the agents of lethal pandemics. He describes how Woodrow Wilson’s decision, in 1917, to enter World War I contributed to making the U.S. a tinderbox for the fire of a pandemic: hundreds of thousands of young men were drafted and collected into many military camps for basic training and preparation before being shipped to France. 40,000 and more lived in close quarters in many camps across the country, creating ideal conditions for the spread of disease. He explains how it was most probably in Camp Funston, in Haskell County, Kansas, in early March of 1918, that the first outbreak started. He writes:

In total, twenty-four of the thirty-six largest army camps experienced an influenza outbreak that spring. Thirty of the fifty largest cities in the country, most of them adjacent to military facilities, also suffered an April spike in ‘excess mortality’ from influenza, although that did not become clear except in hindsight. (169)

Later that year, in September, an explosive outbreak occurred at Camp Devens, near Boston. In a single day, more than 1500 soldiers reported ill with influenza. By late September almost 20% of the camp were sick, and 75% of those needed to be hospitalized. And then the pneumonias and the deaths started. And soon thereafter the pandemic started raging in the civilian population. An early and devastating example was Philadelphia, and again the course of the disease has to be seen in the political and historical context. At the time, Philadelphia was led by corrupt and largely incompetent politicians. And in the context of the war and attempts to maintain morale, the authorities and newspapers minimized the outbreak if they reported on it at all. For September 28, a Liberty Loan Parade, an event to promote war bonds, in which thousands would march and more thousands would watch, was scheduled. In spite of being urged to cancel or postpone the event, the city authorities decided to go ahead, thus creating what today we would call a super-spreader event.

The disease was now unstoppable and raced through the country and the world. In the United States, health care systems were overwhelmed, the economy devastated, the social fabric was strained to the breaking point, trust and solidarity were replaced by fear and terror. There were so many bodies that funeral parlors and municipalities could not keep up, families often lived with the corpse of a family member in their houses and apartments for days or longer.

In the United States, the 1918-19 pandemic caused an excess death toll of 675,000 people. The total population then was about 105 million while at the time Barry published his book it was about 300 million. At that time a comparable death toll would have been 1,750,000. The global death toll is now estimated to have been between 50 and 100 million people.

*

In closing, allow me to return to John Barry’s 2018 “Afterword” and to leave you with some quotes:

So the problems presented by a pandemic are, obviously, immense. But the biggest problem lies in the relationship between governments and the truth.

Part of that relationship requires political leaders to understand the truth – and to be able to handle the truth. If there is a lesson from the 2009 pandemic [swine flu, J.K.], it’s that too many governments were incapable of doing so. (459)

So the final lesson of 1918, a simple one yet one most difficult to execute, is that those who occupy positions of authority must lessen the panic that can alienate all within a society. Society cannot function if it is every man for himself. By definition, civilization cannot survive that.

Those in authority must retain the public’s trust. The way to do that is to distort nothing, to put the best face on nothing, to try to manipulate no one. (461)

John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza is obtainable through Darvill’s Bookstore.

Many thanks for this concise and very timely review.