— Book review by Jens Kruse —

On New Year’s Day, 2013, Gene Weingarten – two-time Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and writer for The Washington Post – steps into the Old Ebbitt Grill in Washington, D.C. with an old green fedora in his hand. From it, in three successive drawings, he asks random patrons of the restaurant to draw from paper chits denoting the days of the month, the months of the year, and a range of years, 1969 – 1989. After three drawings he has a date: December 28, 1986, a Sunday.

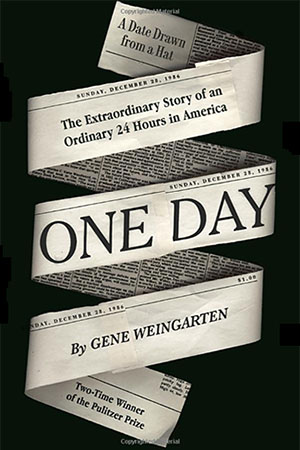

More than six and a half years later, more than 500 interviews, in person and on the phone, later, after prodigious research in newspapers large and small, television station archives, court records, and more, he was finally able to publish One Day. The Extraordinary Story of an Ordinary 24 hours in America. And we, much to our enlightenment and enrichment, are able to read it.

Weingarten’s book does not have a table of contents; it does not need one. After an “Introduction” in which he explains the genesis of his quirky idea for a book, the opening chapter is called, simply, “The Day.” It starts with: “It is a Sunday, the 362nd day of the year of Chernobyl and Challenger, when preventable failures of technology humbled two superpowers” (19) and ends with: “It was a day unlike any other, 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.0916 seconds of a planet speeding around Earth’s axis at the velocity of a bullet, occupying a spiral of space that will never be revisited” (26). In between these opening and ending lines of this first chapter, Weingarten treats us to a kaleidoscopic preview of the stories to come in the chapters that make up the body of his book. These thumbnail sketches are little gems in their own right, but of course they are suggestive, not comprehensive, they are incomplete for the best of reasons: they make us want to know the full story.

And so we turn the pages, from chapter to chapter, story to story. These chapters are chronologically arranged: from “12:01 A.M., Charlottesville, Virginia” to “11:55 P.M, Oakland, California” Weingarten takes us through the “Ordinary 24 Hours in America” on this day, Sunday, December 28, 1986.

And as it turns out there is really no such thing as an ordinary day, at least not when you begin to look hard enough into the lives of “ordinary” human beings and fellow citizens. For some of them this day shattered their lives, for some of them it made their lives, and for some of them, extraordinarily, mysteriously, it did both.

Late in his last chapter Weingarten writes:

By that point, midnight had passed. The twenty-eighth day of the twelfth month of the year was done. Eva Basley had gotten her new heart and Todd Thrane had lost his life trying to save babies, and baby Michael Green had been burned beyond recognition and Cara Knott had been pulled, dead, from a culvert and Ed Koch had been booed by his loyal constituents and the Confederate flag was marched home and someone had stolen the weather vane and Terry Dolan and Joel Resnikoff had died of AIDS and Brad Wilson had somehow survived his helicopter crash and the football replay had gone on and on and little Heather Hamilton had saved the princess. The day would quickly fade into imperfect memory. The events of a single day are hard to hold on to in the relentless flow of time, the most powerful and mysterious force of all. Everything moves on. (363)

While the thumbnail previews of the book’s first chapter had made us look forward to the fully exfoliated stories hiding in those teasers, the reprise above allows the readers of the chapters in between to live through the stories of this “one day” once again in a dizzying time-lapse recapitulation: to encounter one more time the human beings whose stories animate this book. They are human beings that act morally and immorally, smartly and stupidly, honorably and despicably, decently and criminally, courageously and cravenly, predictably and inexplicably. They are human beings that are defeated by unimaginable challenges, or rise to defeat them.

Weingarten tells their stories with empathy, openness, and wonder. And in doing so he elucidates not just the circumstances of their individual lives but the context of the society they live in. By the hard work of reporting and research and by the alchemy of storytelling Weingarten has given us a detailed, deeply layered, complex account of one day in American life.

Beyond that: even though Weingarten never makes that claim, his book’s implicit thesis is that, in fact, given the same treatment of any 24 hours any one day would yield a similarly complex kaleidoscope of events and stories, stories that, fully and expertly told, have lessons for us.

In the last sentences of his book Weingarten summarizes those lessons

like this:

We are all serving time on death row; only the length of our stay is indeterminate. Dead people, walking. If our lives are to be fulfilling, we must be grateful for the experience alone.

Those who have had a brush with death and survive, who have come nakedly face-to-face with their own mortality, get a visceral glimpse of that truth. It is terrifying and humbling; it changes perceptions and priorities and delivers awe. But denial tends to quickly take hold again – we navigate our terrors through denial – and we return to the mundane: our old habits, our take-for-granted thinking. Each moment becomes once again just another in a series of unremarkable moments, instead of a soul-searing blast of the inexpressible wonder of being. (366-7)

One Day. The Extraordinary Story of an Ordinary 24 hours in America.

(New York: Blue Rider Press, 2019) can be checked out from the Orcas

Library. It is available through Darvill’s Bookstore.

Thank you, Jens, for these colorful and enticing book reviews. I look forward to each one and to having time to read each one, too.

Thanks, Janice, for reading.

What a fantastic review, Jens! Thank you; I’m so glad the library has this book because your review, and the selections you share with us, entice me to read it.