||| FROM MICHAEL RIORDAN |||

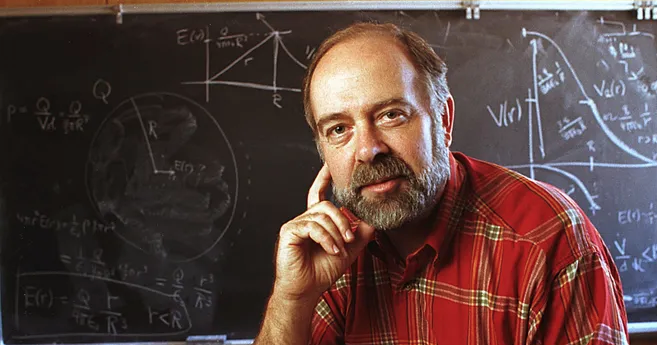

A noteworthy Orcas Islander, physicist Roy Schwitters, passed away earlier this month. He had previously served as Professor of Physics at Stanford University, Harvard University and most recently the University of Texas before retiring to Orcas Island with his wife Karen a few years ago. He also was the first and only director of the ill-fated Superconducting Super Collider project in Texas before it was terminated by Congress in October 1993.

An avid mountaineer who grew up in Seattle, Roy had deep Orcas Island roots, as his mother graduated from Orcas Island High School in the early 1930s — a cousin of the Willis family in Olga. As much as possible given his busy academic schedule, Roy and Karen tried to attend the annual July 4 family gatherings on Willis Lane, eating hamburgers and pitching horseshoes with the best of them. At one of those gatherings, they spotted a waterfront house for sale on Willis Lane and purchased it soon afterwards.

I had known Roy for over 50 years, first as a fellow member of the Delta Upsilon fraternity at MIT and then as the teaching assistant in my graduate particle-physics course there. We kept in touch over the years, largely due to our common interest in that discipline.

For his principal scientific contribution, to the mid-1970s discovery of the charmed quark, Roy was awarded the Alan T. Waterman Award, the National Scientific Foundation’s highest honor. The following article from the Austin American more thoroughly describes his life and works.

———————————————————–

Nationally prominent physicist Roy F. Schwitters — laboratory director for the ambitious yet incomplete Superconducting Super Collider project in North Central Texas during the 1980s and ’90s — died Jan. 10 of cancer on Orcas Island, Washington. He was 78.

“Schwitters was a dynamic leader in the field of experimental high-energy physics,” said William Coker, a physics professor at the University of Texas, “and therefore the natural choice to become director of the Texas Superconducting Super Collider project. Later, as a faculty member at the University of Texas, he remained a force to be reckoned with, but his leadership style was deceptively ‘laid back.'”

The Texas SSC, a ring-like tunnel 54 miles in circumference near Waxahachie, was intended to explore the edges of knowledge about energy and matter. It would have been the world’s largest and most energetic particle accelerator. Predicting an economic bonanza from this experimental project with national security significance, the state of Texas contributed $400 million, and the federal government allocated at least $1.6 billion to design and built it. It was canceled in 1993.

A principal discover of the ‘charm quark’

Born in Seattle in 1944, Schwitters earned degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He taught at Harvard University, Stanford University and the University of Texas.

“Roy grew up in Seattle, and one of his early memories is of seeing the inaugural flight of the Boeing B-52 fly past his school, which awakened his interest in science and technology,” wrote his friend, author and journalist Lawrence Wright on Schwitters’ death. “His own first ride in an airplane had to wait until he left to study physics at M.I.T.”

At that university, he joined the circle of charismatic Harold “Doc” Edgerton, who applied physics to sonar and deep-sea photography, pioneered ultra-high-speed photography, and invented the hydrogen bomb detonation device.

Early in his career, Schwitters helped develop particle colliders, including those at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. Using the Stanford Positron Electron Accelerating Ring, he was one of the principal discoverers of the “charm quark” in 1974.

“An iconic picture of the detector features Roy in the middle of it,” said Karol Lang, a physics professor at UT. “His next mark on the field was the leadership of the (Collider Detector) experiment at Fermilab, where he showed his managerial skills, which were fortified by deep technical knowledge and intuition.”

Schwitters, therefore, was a natural to lead the gigantic Texas SSC project. In 1993, Congress cut the program in a budget-saving move, in part because America’s intense national security rivalry with Russia had ended with the close of the Cold War.

In fact, with no guarantees of what might be discovered, the project had always been a hard sell to those skeptical of the value of pure science.

Schwitters famously called the funding cut “the revenge of the C students.”

Among scientists, in Austin and beyond

“Bitterness was not a part of Roy’s personality,” Wright wrote. “He was kind and jovial and he adored teaching.”

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Thank-you, Michael, for sharing your personal remembrances about Roy Schwitters and the Austin American article.

What a full life he lived.