All over the West, a housing crisis is causing workforce shortages, crippling local businesses, and threatening the culture and existence of mountain towns as we know them. But amid the doom and gloom, some people are fighting for solutions.

||| FROM OUTSIDEONLINE.COM ||| REPRINT AT REQUEST OF A READER

Once upon a time, there was a magical town named Crested Butte. It was nestled in a valley in southwest Colorado among beautiful, towering peaks and shivering aspen groves. The mountains made the town difficult to get to—it lay, quite literally, at the end of a two-lane road. There were a couple of dirt roads in, too, but after the late-fall snowstorms, they became impassable. And so the mountains protected the town.

For a long time things were good. In the winter, there was powder to ski; in the summer, there were trails to ride. Most important, there were not so many visitors, at least compared to other mountain towns. Crested Butte was far from the constant roar and snaking brake lights of I-70, Denver’s thoroughfare to the mountains; and some might also say the family who owned the ski resort did a pretty crappy job of marketing it. But the residents liked it this way. Their town had not sold its soul for tourist dollars and high-speed lifts like Aspen or Vail. They still had their T-bars, their funky culture, their cruiser bikes parked unlocked on the streets.

But things began to change. Crested Butte was discovered, in the same way that other magical towns were being discovered. More people began to visit, and those people told their friends and posted glowy photos on Instagram. More people bought second homes there, driving up the price of real estate. Then came the Airbnbs and the VRBOs, which allowed second-home owners to earn a lot more money renting to tourists than to the people who actually lived and worked there. The locals found it harder and harder to afford a place to rent or buy in town. They began to leave, moving 35 minutes downvalley to Gunnison or disappearing from the area altogether. By 2017, some wondered if Airbnb was going to kill this, and other, magical towns.

Then came the pandemic. Maybe this part of the story you know. Unchained from their desks, the hordes of newly remote white-collar workers descended upon all the magical mountain towns, and in just one year, the median list price for a home in Crested Butte jumped 40 percent, to $895,000. Rents soared, too—20 to 40 percent in Colorado ski towns like Crested Butte, according to one June 2021 report. Meanwhile, both for-sale and rental inventory plummeted. Now it was nearly impossible for locals to find housing.

And one day in the summer of 2021, the town simply stopped working. Restaurants began to shut down for parts of the day or entire days of the week. “Help Wanted” signs appeared up and down the main street of Elk Avenue. It didn’t matter that the sidewalks teemed with tourists freed from COVID lockdowns and ready to spend. Lines grew. People waited an hour and a half, two hours for food. What’s happening? visitors grumped.

The newspapers reported on the problem: it was so hard to find affordable housing in town that there weren’t enough people left to work in town. It wasn’t just Crested Butte, either. The headlines popped up all summer long:

“Housing in Jackson: Is This a Crisis?”

“Ketchum Has Plenty of Available Jobs but Workers Can’t Afford Housing”

“Tahoe’s Hiring Crisis Unraveling the Region’s Small Businesses”

In July, NPR shone its spotlight on Crested Butte: “Short on Workers, This Resort Town Has Stopped Marketing Itself to Tourists.” Indeed, by that point the valley’s tourism association was running ads in the local paper informing visitors about the housing shortage and asking them to be patient with slower than usual service. The window of the iconic Wooden Nickel steakhouse displayed an “Employee Crisis Limited Menu” notice. The sign went on to explain that, on top of having “barely enough employees to run the restaurant,” some cooks had just quit. “We’re sorry we’re unable to provide the menu you expected,” it told would-be diners. “Thank you for joining us on this challenging evening.” Across the street, at the Brick Oven Pizzeria, someone had affixed a sticker on the wall of the men’s bathroom that read, simply, “SAVE CB.”

The magical town, it seemed, was in serious trouble.

Reality check: unless you’re one of the über-wealthy, living in a mountain town has never been the stuff of fairy tales. The limited supply of affordable housing for workers has been a challenge for decades. Ritzy-glitzy Aspen claims the oldest workforce-housing program among North American ski towns. As early as the 1970s, it began slapping deed restrictions—requirements like maximum income levels for buyers or maximum resale values written into the title of a property—onto homes in order to preserve their affordability.

Crested Butte’s own affordable-housing program was inspired by Aspen. In the 1980s and ’90s, the town acquired large tracts of land for future housing development and incentivized property owners to build accessory dwelling units above businesses and garages to house local workers. Deed-restricted residences still represent 25 percent of Crested Butte’s housing today. In 2017, its town council also had the prescience to slow the growth of Airbnbs and other short-term rentals by capping the total number of licenses at 30 percent of all area homes.

But all that groundwork hasn’t been enough. A May 2021 Gunnison Valley housing-needs assessment estimates that the valley is short 490 homes to accommodate its total required workforce. Since 2016, only two out of three local workers in the North Valley—which encompasses the towns of Crested Butte and Mount Crested Butte (populations 1,723 and 876, respectively), as well as neighboring unincorporated areas like Crested Butte South—have actually been able to live in the North Valley. The rest commute from Gunnison or farther away. As depicted in a recent clip by Vice News, others even live in their vehicles in the surrounding national forest. And Crested Butte is hardly the worst off among its peers: in Pitkin County, where Aspen is located, just 40 percent of workers live where they work; in the North Tahoe–Truckee region in California, that figure is only 50 percent; and Vail houses less than 30 percent of its workforce.

When the situation reached its breaking point over the summer, Crested Butte officials acted swiftly. In June, the town council declared a state of emergency, the first time a Colorado municipality had used the designation for a housing crisis. This enabled them to bypass certain municipal codes and provide some immediate relief, like purchasing a six-bedroom bed-and-breakfast and converting it into dorm-style housing for local workers. They also began allowing RV and tent camping on private property in town. In July the council issued a moratorium on new short-term rental licenses for a year, and officials resumed discussions about a controversial tax on empty homes, which they had started in 2020 but tabled for the pandemic.

Similarly urgent conversations were happening in resort towns all over the Mountain West. “I’m not sure I know what the one solution is,” says George Ruther, housing director for the town of Vail. “I think I know what the solution is not. We’re not going to build our way out of this problem. It’s too costly. I dont think it’s going to be solely by regulatory means either. Vail, like Park City, like Jackson Hole, like Aspen—all of these communities have regulatory land-use tools like inclusionary zoning or development impact fees. But guess what we all have? We all have housing problems.”

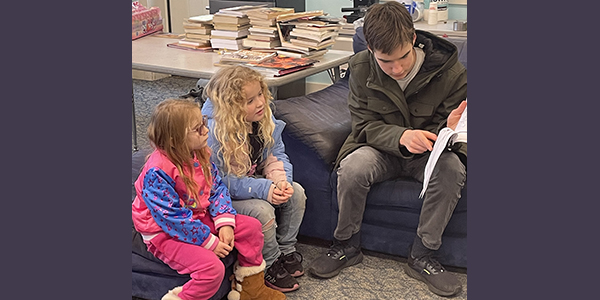

Crested Butte homes (Photo: krblokhin/Getty)

The boy came from New Jersey. The son of a second-home owner, Will Dujardin arrived in the magical town of Crested Butte by way of the twice-annual ski trips his family took to their condo on the mountain. As a teen he was a talented freeskier, good enough to compete against other young men from around the country, and when he was 22 he returned after college, thinking he’d ski-bum for a year before getting a “real job back east.” But then he discovered mountain biking, which was how he learned that the summers in Crested Butte were even better than the winters.

Seasons passed. Dujardin became the head coach of the youth freeride program on the mountain, and it was a good job, a rewarding job, but only ever a seasonal job. So the rest of the year he painted houses and bussed tables. As time went on, he saw friends leave the valley because they couldn’t afford to stay. He watched properties that used to house families convert to Airbnbs. Finally, in 2017, he decided to do something about it. He ran for town council, was elected, and in 2019 was nominated to mayor pro tem by his fellow council members.

On town council Dujardin spoke passionately about the importance of affordable housing. He went to meetings, answered emails, and let concerned citizens bend his ear at the bar. There were wins, like watching friends buy first homes in a newly completed affordable-housing development. But there were losses, too. Over four years serving on council, Dujardin learned that compromise was the only way to get shit done, but it also often meant that everyone was a little unhappy at the end.

In an ironic twist of fate, last spring Dujardin, who is now 35, lost his own housing when his landlord attempted to sell the two-bedroom rental Dujardin had always shared with two or three housemates. A few months later, he managed to buy a small condo in town with the help of some family money. He hates that detail, but he shares it openly because it proves his point that the only people who can make it in Crested Butte are the privileged.

The first time we talk on the phone, I tell Dujardin that I’d like to do a story about not just the doom and gloom of the housing crisis but the solutions being proposed and the people fighting to save these towns. People like him. It’s early August, and the months of city council meetings that have gone past midnight have clearly worn on him. “I appreciate that sentiment,” he sighs, “but it’s been really challenging to keep the solutions forward-thinking and positive when you’re constantly badgered by people who are self-righteous in their beliefs.”

Mountain towns have certain characteristics that make housing particularly challenging, including topography, small budgets, and limited availability of land (78 percent of the acreage in Gunnison County, for example, is federally owned by agencies like the Forest Service). But the most formidable opponent facing Dujardin and his compatriots is one facing affordable housing proponents everywhere: NIMBYism. “This is a lot of the reason you see most of the opposition,” says Roland Mason, Gunnison County’s commissioner and chair of the Gunnison Valley Regional Housing Authority. “People don’t want the town to change from when they moved here.”

Mason and Dujardin both cite the doomed Brush Creek development, which would have added 156 units of deed-restricted housing in a neighborhood that was also home to a golf course and a country club. The project was initially proposed in 2017 as a 240-unit property, but over the course of a two-year review process, it was whittled down to 156 units.

All along the way it met with fierce opposition. At an October 2017 meeting for public comment, over 200 people showed up. Some of the project’s opponents formed an organization called Friends of Brush Creek, which Dujardin says was primarily second-home owners. I couldn’t verify the makeup of the group, but I did find a sampling of opposition letters written to the council ahead of another October 2017 meeting. From one: “Like all other homeowners in Skyland, we purchased our property because of the beauty of the area and the thoughtfully planned development of housing,” wrote Charles and Jennifer Bess. “To allow such a drastic change in density would result in a new urban-level community in the middle of a suburban and country setting, a change that would be unconscionable.”

It wasn’t just wealthy homeowners, either. Influential long-time residents like Mark Reaman, editor of the Crested Butte News, also opposed the project. Reaman wrote numerous op-eds against it, including one in September 2017 titled “Bringing a Taste of Denver to Brush Creek,” in which he compared the development to “what might as well be an Aurora apartment complex,” referencing a diverse and sprawling Front Range suburb. Eventually, the developer said that the project was no longer financially feasible with all the stipulations added in the review process. In October 2019, the proposal died.

New developments aren’t the only worker-housing initiatives that are contentious. Attempts to rein in short-term rentals in some towns have also met with strong resistance. In Telluride, Colorado, where the joke goes that the billionaires have pushed out the millionaires, citizens placed an initiative on the November ballot for the town’s first-ever short-term rental cap. When I speak to Telluride mayor DeLanie Young in August, she tells me that she’s received dozens of emails in response, mostly against the measure. The writers are almost all second-home owners, and some own three or four properties, she says. As in many ski towns, second-home owners possess a significant portion of the housing stock in Telluride—54.4 percent of homes in town qualify as vacant, according to 2019 data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The notes Young received have common refrains: People are going to lose their jobs, is one. This is going to ruin your economy, is another. (The citizens’ measure ultimately did not pass, though a measure to put a two-year moratorium on new short-term rental licenses did.)

Young is a first-term mayor who, in a past life, was the programs manager for the regional housing authority. Prior to that, she was a librarian. When she was running for office, people thought of her as “the housing lady,” she says.

“I think the thing people need to be reminded of is, this housing crisis is not unique to our town or community,” she tells me at the end of our call. “This is happening all over our entire country and other countries. We are, as a human race, in severe need of a complete culture shift in so many ways, and housing is one small piece of that. I think it’s just important that people look outside themselves, because this is affecting so many people. It’s horrifying. Shelter! It’s a basic human need.”

READ FULL ARTICLE: www.outsideonline.com/culture/essays-culture/how-to-save-a-ski-town-west-tourism-economy/

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**