Work above the Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee Dams has proven that salmon will return home, pressuring the government to uphold obligations to Upper Columbia United Tribes. With further litigation on hold, the federal government has committed more than $200 million for salmon reintroduction efforts led by Native nations

||| FROM INDIAN COUNTRY TODAY |||

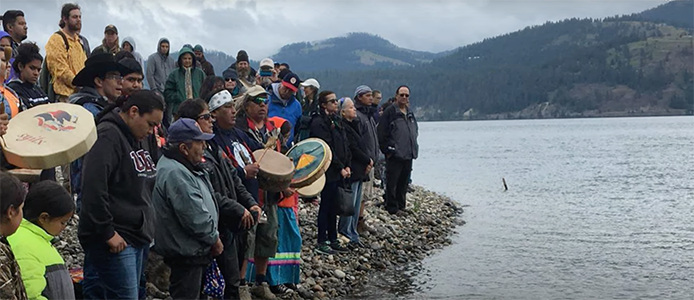

Down the curved walkway just past the Chief Joseph Hatchery, the sounds of soft laughter and friendly hellos mixed with the roar of the Columbia River as it cascaded in streams through the Chief Joseph Dam. Near the hatchery raceways, spiritual leaders of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation led a ceremony to give thanks for the sacrifice of the first salmon of the season.

“This work that we do lifts our spirits,” said Jim Andrews, Colville, told the crowd gathered to participate in the First Salmon Ceremony. “We thank Creator for this day today. We thank mother earth for the water we drink and the air we breathe. Most of all, we come here today to honor the spirit of the salmon that comes back every year and was the first one to give itself up to the people.”

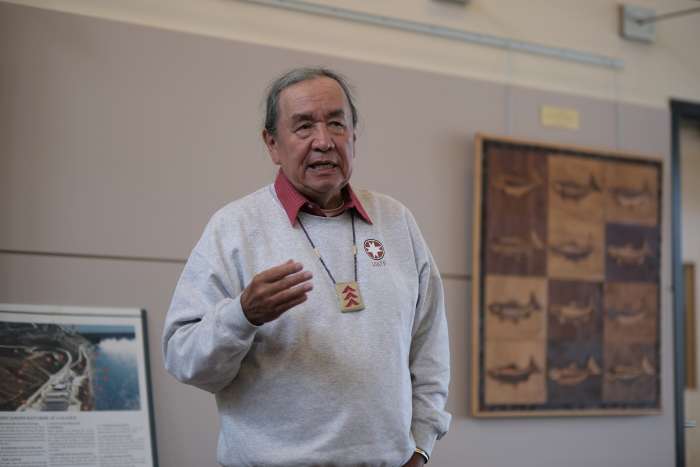

After a song honoring the first salmon, Darnell Sam, Colville, fileted it in preparation for eating during the ceremony. Attendees entered the Chief Joseph Hatchery, where Randy Lewis, also a Colville citizen, shared part of the Colville creation story.

A view of Chief Joseph Dam, outside of Bridgeport , Wash., on May 23, 2024, as The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation celebrate their First Salmon Ceremony. This is the last place anadromous salmon can reach as they swim upstream from the Pacific Ocean as there is no fish ladder allowing them to navigate though the dam. (Photo by: Alex Milan Tracy/Underscore News)

Lewis explained that when man was first placed here he was starving. So coyote, who was Creator’s messenger, asked the animal people if they would come forward and offer themselves to man so that they could survive.

“One by one, the animals all declined,” Lewis said. “So they went all the way down the Columbia River. There at the mouth of the Columbia, coyote took his club – his club was his stick of power – and he smashed the water to bring forth all the sea life.”

Coyote asked again if anyone would help man. They all turned away, except one.

“Coyote turned around and was surprised at a small fish – the different salmon were all there,” Lewis said. ‘We will help you but we’ll do it under one condition, that you will allow us to return. Make a promise that we will return year after year.’”

Coyote agreed and brought salmon all the way up the Deschutes River to the Columbia River. From the salmon’s sacrifice, man learned to honor and respect them through song and ceremony.

“Salmon is who brought us ceremony,” Lewis said. “We learned to give thanks for this wonderful gift.”

Member and elder of The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, Randy Lewis, welcomes the gathered community at the Chief Joseph Hatchery during the First Salmon Ceremony outside of Bridgeport, Wash, on May 23, 2024. (Photo by: Alex Milan Tracy/Underscore News)

Salmon people

The Colville, along with many other nations along the Columbia River, have always considered themselves salmon people. The connection to the salmon is as ancient as the people. According to Lewis, until the coming of the colonizers, Rock Island, a little over 75 miles downstream from the Chief Joseph Hatchery, was a continuously occupied community for 9,000 years – predating the first dynasties of Egypt by 4,000 years. During construction of the Rock Island Dam starting in 1929, many of the petroglyphs on the basalt were blasted away. Others were submerged by water due to the dam.

“There’s many around up and down this river,” Lewis said. “We’re not a new people. We are an ancient people.”

That is why in 1942, two years before the Grand Coulee Dam was finished, the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation held a Ceremony of Tears for the loss of traditional fishing sites due to the rising water from the dams. Both Kettle Falls and Celilo Falls, fishing sites central to life since time immemorial for Native nations along the Columbia River, have been completely submerged.

Stephen Noyes, or Sin’Saleetsa, recalled what fishing was like before the dams. In N̓x̌ʷʔiłpcən or Okangan, the name Sin’Saleetsa means “spotted robe,” referring to the patchy fur of deer during the spring and fall when they shed their coats.

Stephen Noyes, an elder citizen of The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, attends the First Salmon Ceremony at Chief Joseph Hatchery outside of Bridgeport, Wash., May 23, 2024. (Photo by: Alex Milan Tracy/Underscore News)

“I came down to the mouth of the Okanagan river with my dad and my uncle,” Noyes said. “They all parked on the hill and built a big bonfire. I fell asleep in the car. At one o’clock or so in the morning, you hear somebody yelling, ‘Here they come!’”

Noyes recalled waking up and looking out to see salmon all across the river. Families would catch loads of fish and when they had passed, people would sit and wait until the next wave of salmon would pass through and start all over again.

“It looked like you could walk across the Columbia on fish, there were so many salmon,” Noyes said.

“That’s what it was like in the old days.”

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**