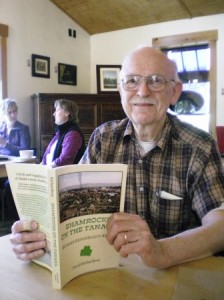

Dave Richardson and his new book, Shamrocks on the Tanana: Richard Geoghegan's Alaska

Dave Richardson prefaces his new book, Shamrocks on the Tanana: Richard Geoghegan’s Alaska, saying, “When I was a small boy growing up in Friday Harbor, Washington, I loved to visit the little country newspaper shop with its clutter and clamor, and those delicious old-time smells of printer’s ink and hot lead.”

That printer’s shop was owned by Jack Geoghegan, from one of Orcas Island’s pioneer families, who regaled Richardson with tales of his older brother Richard’s adventures in Alaska – the adventures of languages, history and cryptology.

Richardson, who with his wife Myra Jo has lived on Orcas Island for the last 50 years, has always been intrigued by the same kind of adventures.

So it should come as no surprise that his latest endeavor is Shamrocks on the Tanana, the biography of Richard Geoghegan who served as court reporter and attorney-in-fact during Alaska’s territorial days in the early 1900s. In telling Geoghegan’s story, Richardson’s involvement included no small amount of cryptology, historical research and a strong interest in Esperanto, the international language spoken by both subject and author.

Richardson, who grew up in Friday Harbor before attending high school in Seattle during World War II, showed an early aptitude for codes and languages. He knew Morse code, was a ham radio operator, and studied several languages at that age. When Army recruiters came to his school to direct students toward the armed services, they advised him to study Russian before joining in the war effort.

He did so and then, as an Army infantryman, saw the final days of the war behind German lines in intelligence and reconnaissance, interviewing Russian prisoners of war who’d escaped their German captors.

He returned to Seattle to finish his schooling, majoring in Russian at the University of Washington, and then joined the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in its early days. He was sent back to Germany in 1949 as a civilian working for the U.S. Department of Defense, “but it was obvious what we were really doing,” says Richardson.

His job was interviewing individuals and groups that were fugitives from the Soviet Union who claimed to have contacts that would be helpful to U.S. intelligence. “It was all exciting and patriotic, but whether we accomplished anything, I have my doubts,” Richardson says.

During his years in the CIA he took courses in cryptology, “as a hobby, just because it was something I was interested in.” Despite a visit from a lady who came to see him, “recruiting for something very mysterious,” (which he now believes was the National Security Administration), he left the CIA in 1953 when he saw it changing, “going in another direction I wasn’t comfortable with.”

When he came back to Seattle, television was becoming a star on its own, overshadowing its beginnings in radio, and though Richardson “never thought TV would amount to anything,” he wound up working in television until a bout with polio sidetracked his career.

By then he and wife Myra Jo had two small children, and when the opportunity came to move back to Orcas Island and work at the radio tower on Mt. Constitution, they welcomed the return to the more peaceful life of the islands. That was 50 years ago, come November.

Meanwhile, the footsteps, or more accurately, the correspondence of Richard Geoghegan, kept dogging him.

The Geoghegan family, “Ma” Geoghegan, four brothers and two sisters, had come to Orcas Island from England in 1891 and settled in Eastsound, near what is now the Orcas Center. Richard Geoghegan had been crippled by a badly broken leg in childhood, and had pursued the study of languages, earning a scholarship to Oxford University in Chinese. He returned to the Pacific Northwest and initially through a chance encounter, he fell under the radar of James Wickersham and traveled to Valdez and then Fairbanks Alaska when copper and gold mining strikes were filling the courts with claims and counter-claims.

Geoghegan stayed in Alaska, always doing court and reportorial work, and saw the territory settle down from mining claims, fires and floods to a wartime economy where lumps of coal for heating his meager cabin was hard to come by. In the years between, he married a “lady of the night” and was buried next to her, “the darling of his heart,” as his gravestone testifies.

After Richardson first heard of Richard Geoghegan from his brother in Friday Harbor, Richardson wrote to him, asking questions about some Indian languages and received a long reply from him.

Richardson learned that Geoghegan was an early advocate of Esperanto, from his days studying Chinese, Japanese and other Asian languages at Oxford University. Geoghegan published one of the first dictionaries of the international language. His dictionary of the Aleut Language was published just months after his death in 1944.

When Richard Geoghegan died, many of his books and papers came under Richardson’s care. Eventually the University of Alaska began a project to collect Geoghegan’s papers and contacted Richardson in the early 1960s to assist in the project.

Richardson, who has also authored Magic Islands, Pig War Islands, Puget Sounds (a review of radio and television in the NW) and Esperanto: Learning and Using the International Language, dove into the research project with relish.

Many of Geoghegan’s diaries were written in a neat, but elusive script that Richardson undertook to de-mystify, using cryptoanalytical processes to decipher the symbols. He came to believe the script was a form of Pitman shorthand that had originated in England. Richardson wrote to Pitman headquarters to investigate which version of the shorthand had been used.

When Richardson learned that it was a United States version called Graham shorthand, he then sought out books that confirmed his analysis techniques had been correct.

Geoghegan’s letters were colorful and voluminous. “He had a puckish sense of humor, and many observations about what was going on in Alaska.” He combined his work and studies with visits with rough-hewn miners and dance-hall girls, and he kept a correspondence with hundreds internationally. His letters and other writings are housed at the Rasmussen Library at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks.

Richardson’s research went on for a long time, and, like Geoghegan himself, he wrote and received letters from all over the world. His first draft of Shamrocks on the Tenana was completed in 1985.

Through the Seattle Esperanto Society, he was connected with Les and Arlyn Kerr of Cheechako Books, which published the book this spring

Now, “all the threads have been tied together and I can leave it,” says Richardson.

Shamrocks on the Tanana: Richard Geoghegan’s Alaska tells the story of the Alaska Territory’s “raw years” of the early 1900s from the vantage point of “its improbable Irish-American observer.”

Richardson’s prose is concise, yet at times poetic, as when he describes Geoghegan’s first entry into Alaska: “It was a lonesome country he entered. He could hear that in the gulls’ wan cry and see it on the impassive, snow-flecked faces of passing hills. The light fell thin and cold from a low, reluctant sun.”

Richardson relates Geoghegan’s life and loves in the Far North, and sums up his later years, writing, “He filled [his cabin] with his books and papers, and settled down to the life of retiring but self-contended scholarship which he was to pursue all the rest of his years.”

Lael Morgan, professor emerita of the University of Alaska Fairbanks and author of Alaskana books herself, wrote, “Dave Richardson ably captures the engaging personality of one of Alaska’s most unlikely gold rush participants, a gifted but severely crippled Oxford scholar, who overcame his handicaps to become an enthusiastic and important participant in shaping the destiny of the Far North.”

Shamrocks on the Tanana is available at Darvill’s Bookstore.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

i had the pleasure to encounter a bit of Geoghegan’s writings some years ago while working in the office of Esperanto-USA. I found him to be one of the cleverest writers i ever encountered. I am glad this biography is out, and i hope that an anthology of Geoghegan’s writings will appear someday soon.

Is it possible to contact Dave Richardson or at least leave a message? I have come across a wonderful Yukon Gold Rush letter that has great mining detail and mentions several prominent folks by name. I’m sure at a minimum he would enjoy it and it may be beneficial to his research. Thanks, MW