||| FROM AP NEWS |||

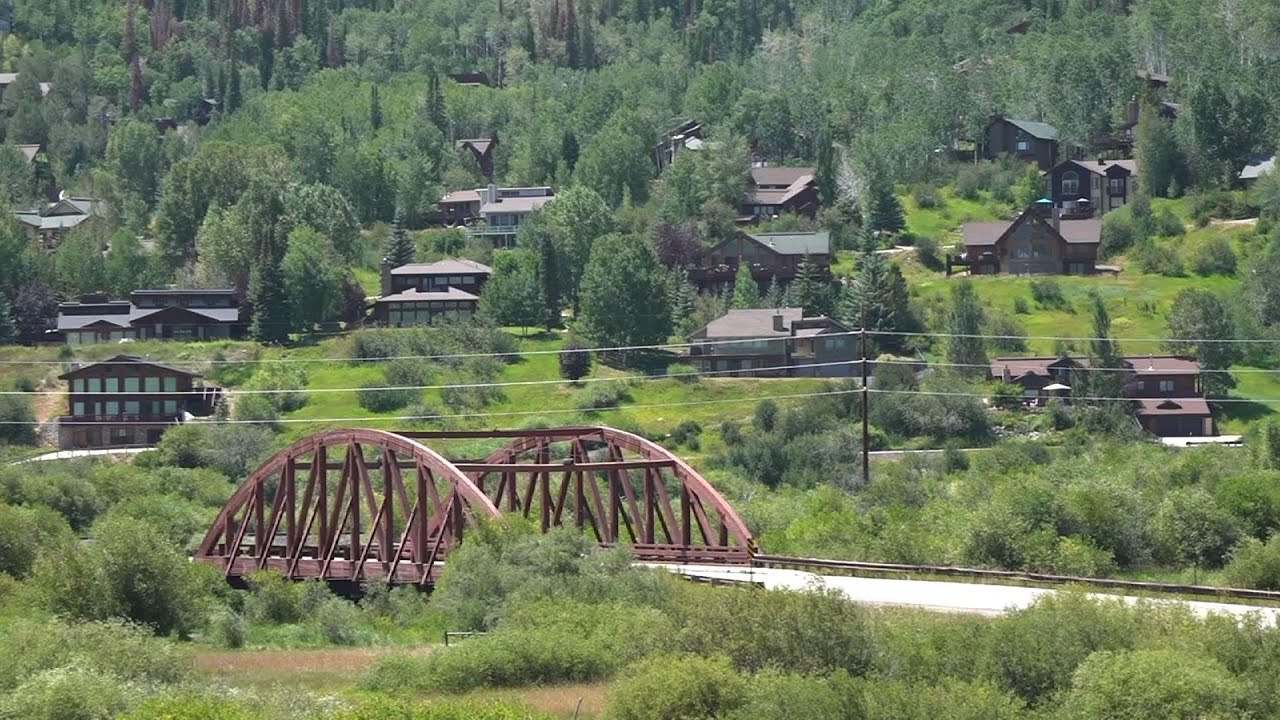

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, Colo. (AP) — In the Colorado ski town of Steamboat Springs, motels line the freeway, once filled with tourists eager to pitch down the slopes or bathe in the local hot springs.

Now residents like Marc McDonald, who keep the town humming by working service-level jobs, live in the converted motels. They cram into rooms, some with small refrigerators and 6-foot-wide kitchens, or even just microwave kitchenettes. Others live in mobile homes.

Steamboat Springs is part of a wave of vacation towns across the country facing a housing crisis and grappling with how to regulate the industry they point to as a culprit: Short-term rentals such as those booked through Airbnb and Vrbo that have squeezed small towns’ limited housing supply and sent rents skyrocketing for full-time residents.

“It’s basically like living in a stationary RV,” said the 42-year-old McDonald, who lives with his wife in a just over 500-square-foot converted motel room for $2,100-a-month, the cheapest place they could find.

McDonald, who works maintenance at a local golf course and bartends at night, and his wife, who’s in treatment for thyroid cancer and hepatitis E, said they will be priced out when rent and utilities jump to about $2,800 in November.

“My fear is losing everything,” he said, “My wife being sick, she can’t do that, she can’t live in a tent right now.”

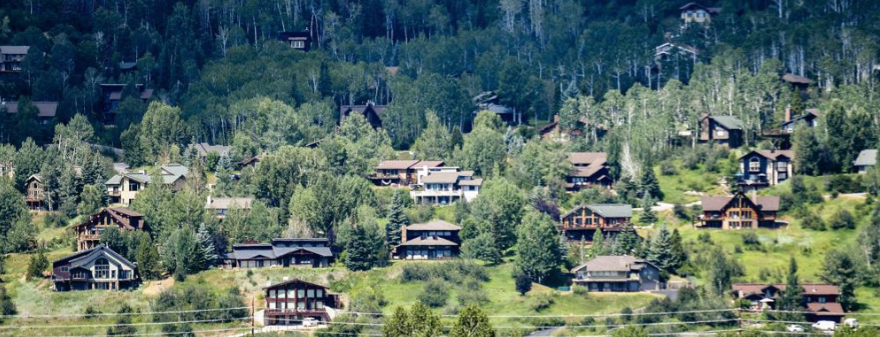

Short-term rentals have become increasingly popular for second homeowners eager to offset the cost of their vacation homes and turn a profit while away. Even property investment companies have sunk hundreds of millions of dollars into the industry, hoping to pull a larger yield from tourists seeking their own kitchen, some privacy and a break from cookie-cutter hotel rooms.

When the pandemic opened the floodgates for remote work, Airbnb listings outside of major metro areas rose by nearly 50% between the second quarter of 2019 and 2022, the company said.

In six Rocky Mountains counties, including Steamboat Springs’ Routt County, a wave of wealth flooded towns, with nearly two-thirds of 2020 home sales going to newcomers, most making over $150,000 working outside the counties, according to a survey from the Colorado Association of Ski Towns.

In June, the Steamboat Springs City Council passed a ban on new short-term rentals in most of town and a ballot measure to tax the industry at 9% to fund affordable housing.

“There is not a day goes by that I don’t hear from someone … that they have to move” because they can’t afford rent, said Heather Sloop, a council member who voted for the ordinance. “It’s crushing our community.”

The proposed tax is strongly opposed by a coalition that includes businesses and property owners, the Steamboat Springs Community Preservation Alliance. Robin Craigen, coalition vice president and co-founder of a property management company, worries the tax will blunt any competitive edge Steamboat might have over other Rockies resorts.

“The short-term rental industry brings people to town, funds the city, and you want to tax it out of existence?” Craigen said. “It doesn’t make sense.”

Visitors booking on platforms like Airbnb spent an estimated $250 million in Steamboat Springs in 2021, according to a coalition analysis of local data. If tourism dropped just 10%, local business in the town of some 13,390 residents would lose out on $25 million.

Larger cities, including Denver and Boston, have stricter regulations, like banning vacation rentals in homes that aren’t also the owners’ primary residences. However, a federal appeals court in New Orleans struck down an ordinance Monday that had required residency to get a license for short-term rentals.

But smaller tourist destinations must strike a delicate balance. They want to support the lodging industry that sustains their economies while limiting it enough to retain the workers that keep it running.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Bumping this article. Because over-selling tourist destinations is the culprit – people should read this because it’s out of hand here too. We are not for sale to the highest bidder. Plain and simple, it’s grift for the few while the many suffer. We must not continue to allow it.

We have begged our supposed representatives for many decades to stop pushing unlimited growth; to allow and encourage OTHER business models, and not make tourism/ real estate/development the SOLE industry, and not continue to condone the Economic Growth element of our Charter to bulldoze our forests and wetland environments and all our other concerns like affordability, environmental quality, and quality of life (not just for humans).

Until we demand rectification and step up for the long haul to change a longtime system of corruption, nothing’s gonna change because working people are locked into low paying service jobs coupled with astronomical housing and essentials costs while we watch profiteers threaten lawsuits to officials who won’t cherish or protect the very things they moved here to protect. We watch as the very things we love are being destroyed… may as well solve the ferry crisis and just build the bridge and put up a MacDonalds and strip malls and 7 story parking garages! Only one problem; our roads are already not able to support the amount of traffic coming in.

I have no answers, except to say that we need a lot more committed people in the long haul to speak up, show up, and effect change. We need to root out the corruption in our system and get up off our collective asses and fight back against the class wars that threaten to extinct us and the way of life that values community and life on earth. I love this community – the same principles that make this a heart-centered community need to apply from the bottom up to the very top – not top down where there is too much temptation for greed. It’s an inside job too, not just fix the symptoms.