||| FROM SUSAN THISTLE |||

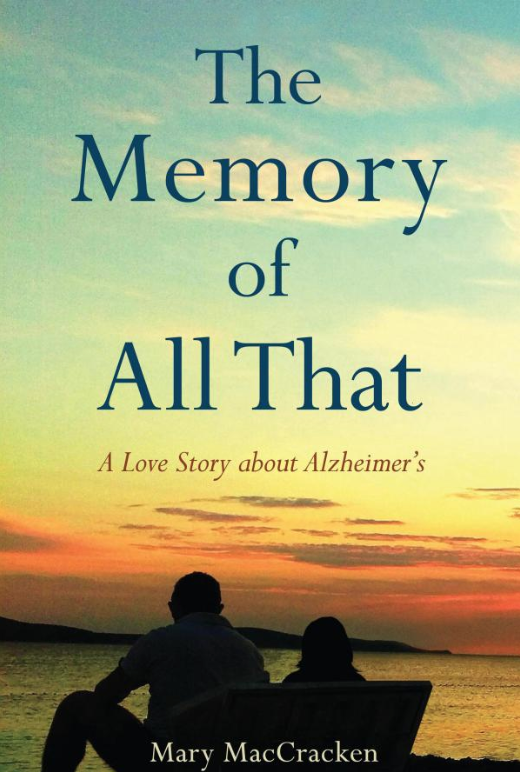

My mother, Mary MacCracken, died before completing her last book, about helping her husband Cal through Alzheimer’s, so I did this for her. She had worked so hard on it, and it was such a good book I felt I just had to finish it and get it published. It was like making a quilt (not that I’ve ever made one). My mother made almost all the squares and laid them out in a pattern. I added a few more squares, rearranged some, and stitched them all together.

What stood out for me, both in going over what my mother had written, and earlier, in watching her care for Cal, was how very much in love they were, and how this love, joined with their resourcefulness and courage, helped them sustain a remarkable relationship all through his disease.

They had always been very supportive of each other, helping each overcome big setbacks at work in the early years of their marriage. Cal was an inventor; my mother taught autistic children. When Alzheimer’s hit, they faced this with same loving determination they’d shown earlier. Cal vowed they’d beat the disease and write a book about it. My mother knew they couldn’t stop his decline. But she supported his brave response and looked for ways to help him enjoy life until the end.

After Cal died, this book took a long time to write, both for my mother and then for me. For many months my mother was just too sad to write anything. Then one day she heard of a writing group, eagerly joined it and began turning out one piece of her story after another.

While this writing group was helpful it also brought problems. My mother made copies of each chapter for everyone in the group, and then brought all these copies home, so she could go over the comments written in the margins and make revisions. This led to a massive amount, piles and piles, of paper. My first task was persuading her to put all the old versions into a couple of big plastic bags, which she reluctantly let me take down to the recycle bin.

We then printed out her latest draft, punched holes in it and placed it in a big white three- ring binder. My mother would sit with this binder propped on her lap, carefully reading through each chapter, crossing out this or that word, adding a different sentence here or there, or sometimes a whole new event. The first three-ring binder was replaced by a bigger red one, holding the next draft, and that one later replaced by yet another. My mother worked on the book every day, polishing it, perfecting it, until the last few months of her life. It was her way of staying close to Cal.

Like my mother, it took me a while to get going on her book. I had my own book to finish, and much other work. But when the pandemic hit, bringing long days of quiet confinement at home, it became a pleasure to read through what she had written and polish it further.

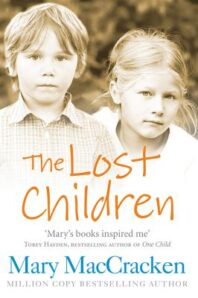

What did I do? My mother had written earlier books, about working with autistic and learning-disabled children, that had done quite well. She knew how to shape a story and use words effectively. I remember her once describing how someone in her group wrote ‘the woman spoke as quietly as possible.” “Whispered,” my mother told me. “She should have just written ‘whispered.’”

What did I do? My mother had written earlier books, about working with autistic and learning-disabled children, that had done quite well. She knew how to shape a story and use words effectively. I remember her once describing how someone in her group wrote ‘the woman spoke as quietly as possible.” “Whispered,” my mother told me. “She should have just written ‘whispered.’”

I did the more pedestrian work of tying these stories together. I also added some dates to clarify what happened when during the disease. Going over the book, fitting its pieces together, led me to see things I hadn’t noticed at first. In the middle years of the disease, for example, somewhat surprisingly, Cal and my mother had a stretch of happy times.

I also went through all her journals, unearthing and including bits she had written earlier and forgotten, or in some cases maybe left out intentionally. Later, after finishing the book I worried that caring for Cal had been far harder for my mother than I’d realized. But then I remembered how thoroughly I’d searched her journals, where she was very honest with herself, and only at one point did she seem really discouraged. “Dark times,” she’d written, after several crises, ending with a long struggle to get Cal through his medications (he kept dropping his pills into a glass of water rather than swallowing them).

Shortly after this, my mother reluctantly realized she had to let Cal go to a memory care unit—not because she failed to care enough (few loved as deeply as they did) but as love alone proved insufficient. The disease just grew too difficult. Still, she and Cal shared moments of joy. “We didn’t beat Alzheimer’s,” her last chapter concludes. “But it didn’t win either. We stayed close and loving through all the years and had sweet times until the end.”

My hope is that her book can help others handle the challenges of dementia as well as they did.

An award-winning bestselling author, MARY MACCRACKEN wrote four books about her work with autistic and learning-disabled children: Circle of Children, Lovey, City Kid, and Turn-About Children. Her books have been published in fourteen countries and the first two were made into movies for television, starring the actress Jane Alexander. Her books have recently been republished (the first and last under new titles, The Lost Children and A Safe Place for Joey) and still attract a wide readership. Mary spent her last years with her husband, Cal, an inventor with eighty patents, at Kendal at Hanover, a Continuous Care Retirement Community in Hanover, New Hampshire, and the decade after his death writing about their experiences dealing with his disease. Learn more at http://marymaccracken.com/

For more information visit https://marymaccracken.com.

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION BY NW BOOK LOVERS

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**