||| FROM RUSSEL BARSH for KWIAHT |||

The chance of finding a tick on yourself or one of your pets in San Juan County is greater than previously believed, but only about ten percent of island ticks are infected with pathogens that can cause you harm. Those are the findings of a year-long study conducted by the nonprofit conservation laboratory Kwiaht, which identified and tested more than 150 ticks collected by islanders and visitors.

Ticks were found on all of the ferry-connected islands, as well as Waldron, Obstruction and Canoe islands in San Juan County, and both Cypress and Burrows islands in Skagit County at the east end of the archipelago. The largest number of ticks came from Orcas (52%), followed by San Juan Island (35%); only a small number were collected on Lopez (6%), suggesting that the distribution reflects ecology rather than the number of people on each island. Most ticks were encountered in backyards and residential areas, as opposed to trails through undeveloped public lands; and most ticks were found on dogs (72%) rather than people (19%). A few ticks were collected from cats, horses, foxes, deer, and lizards.

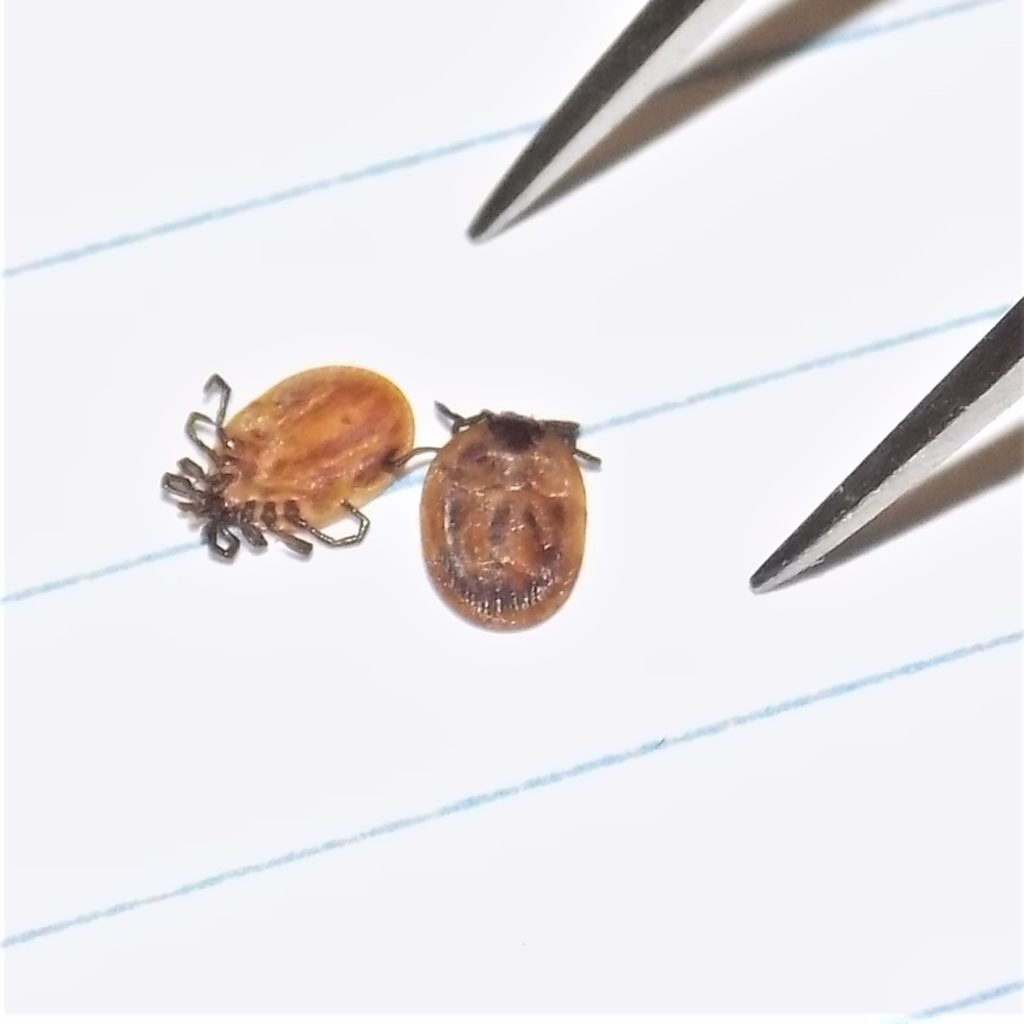

While the great majority were native Western Black-legged ticks (Ixodes pacificus), about one in ten ticks collected were not native to the Pacific Northwest: the eastern Black-legged tick or “deer tick” (Ixodes scapularis) and American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), both originally from east of the Rocky Mountains, and the Western dog tick (Dermacentor occidentalis), native to California. Few deer and dog ticks have previously been reported from Washington State, mainly east of the Cascades.

The presence of non-native ticks in the San Juan Islands is most likely a result of people bringing dogs with them on road trips from California or eastern Washington. Ticks can remain attached to a host for up to 100 hours: more than enough time to drive to the Anacortes ferry terminal from as far away as the Great Lakes or Midwest.

Although ticks appear to be more widespread, diverse and abundant in the islands than previously reported, only one in ten tested positive for a pathogen known to affect humans, dogs, or wildlife such as Anaplasma, Mycoplasma, Babesia, Rickettsia, and Ehrlichia. Babesia was found in five percent of the ticks tested; this malaria-like protozoan is a growing concern nationwide, and only a few years ago was thought to be absent in Washington State. By comparison, no island ticks tested positive for Borrelia, the cause of Lyme Disease, which has been reported from several nearby mainland Washington counties.

The likelihood of contracting a tick-borne disease in the San Juan Islands remains relatively low in comparison with most of the rest of the United States. Precautions are recommended, especially during questing season for ticks, which in the San Juan Islands in 2021-2022 was February through June, with a peak in March or April when two-thirds of the ticks in the study were encountered. After hiking, walking a dog or working outdoors in tall grasses or shrubs, check thoroughly for ticks. Sooner is better; removing a tick within 24 hours greatly reduces the probability of infection.

Residents and visitors are also urged to avoid bringing infected ticks inadvertently to the islands. When arriving from the mainland, check yourself and your dogs thoroughly for ticks. And wash clothing in hot water to prevent hitchhiking ticks from being released in your home, lodging or campsite.

Kwiaht is continuing its tick-surveillance program for another year in cooperation with the state Department of Health. Ticks discovered on people or pets should be set aside in a plastic sandwich bag or paper envelope and mailed to Kwiaht, POB 415, Lopez Island 98261. Please include a note with the date and location where the tick was encountered, and the host (a person, pet or other animal). If you traveled to the mainland within a week prior to discovering the tick, mention that as well. Include your email or a daytime phone number so that you can be notified if a pathogen is detected by testing.

“We still want to see what the 2023 peak questing season looks like,” says study coordinator Russel Barsh. “It remains unclear whether 2022 was an unusual year in terms of weather and tick behavior; and it is uncertain whether ticks or tick-borne pathogens are increasing.”

The first year of this study was made possible by the San Juan Island Community Foundation, the Orcas Island Community Foundation, and the Lopez Thrift Shop, and by the generous donors that support them.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Interestingly, I found fewer ticks on my dog and myself this year while walking the brushy areas along the east side of Turtleback than I did the last two years. I wonder if the lower deer population had anything to do with that?