Without passageways to cross dams along the Columbia, salmon are dying. Tribes say the U.S. government isn’t cooperating as they try to help the fish recover.

||| FROM CROSSCUT ||| Posted at request of Orcasonian reader

Crystal Conant was camped for the night on a bluff overlooking the upper Columbia River in northeast Washington, beading necklaces by the glow of a lantern.

The next morning, hundreds would gather at Kettle Falls for the annual salmon ceremony, held since time immemorial to celebrate the year’s first fish returning from the ocean. Conant and fellow organizers needed necklaces for everyone who would come. Honoring the gift of salmon, she said, requires giving gifts in turn.

Behind them, friends and family had formed a drum circle inside the wooden husk of an old Catholic mission. Back when the salmon were still running up Kettle Falls, the sound of dozens of drum circles would have thundered across the plateau.

But there is only one circle now. And there are no salmon.

The fish cannot get past two federal dams, masses of concrete each hundreds of feet tall. The construction of those dams, which began more than 80 years ago, rendered salmon extinct in hundreds of miles of rivers and destroyed the area’s most important fishing grounds.

“The salmon still keep trying to come, and they come and they hit their little noses on the dam, over and over, ‘cause they hear us calling,” said Conant, a member of the Arrow Lakes and Sanpoil tribes. “So we’re going to keep having our ceremonies and we’re going to keep calling the salmon home until they get here.”

This is part two in a series produced in partnership with the ProPublica Local Reporting Network. Part one: PNW hatcheries aren’t saving salmon, investigation finds.

After nearly a century without salmon, Conant and other members of upper Columbia River tribes want to reintroduce the fish into waters long blocked by the dams.

But there’s been something blocking those efforts, too: the Bonneville Power Administration.

The U.S. government promised to preserve tribes’ access to salmon in a series of treaties signed in the 1850s. Upholding those treaties now rests in no small part with Bonneville, a federal agency little known outside the Northwest that takes hydropower generated at Grand Coulee and other dams and sells it wholesale to electric utilities, primarily in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. Decades ago, Congress placed the agency at the center of salmon recovery, giving it conflicting mandates: protect fish and fund their recovery, all while running a business off the dams that have reduced fish populations by the millions.

Grand Coulee Dam, with the Lake Roosevelt reservoir behind it, was built between 1933 and 1941. (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation)

For decades, judges have admonished the federal government over its failure to do more to protect Columbia River salmon. Most recently, the Biden administration in March took the unprecedented step of acknowledging the harm dams have caused to Native American tribes and calling for an overhaul of Columbia River Basin management. Bonneville, the government’s money-making arm on the Columbia, is the federal agency involved in every measure the Biden team is discussing to save salmon.

But an investigation by Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica has found that Bonneville has, time and again, prioritized its business interests over salmon recovery and actively pushed back on changes that tribes, environmental advocates and scientists say would offer the best chance to help salmon populations recover without dismantling the entire dam system.

Colville tribal member Shelly Boyd looks over the waters covering the historical fishing grounds of Kettle Falls. The falls, where tribes from the Northwest gathered for thousands of years to fish for salmon, were submerged with the creation of Grand Coulee Dam. (Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB)

The agency said it has invested heavily in supporting salmon and sacrificed revenue to make dams safer for fish. It said any limitations on its fish and wildlife measures are the result of financial pressures.

In response to the news organizations’ findings, Bonneville spokesperson Doug Johnson said in a statement that the agency and its federal partners “will continue to participate in regional discussions on long-term strategies to address the protection and enhancement of salmon and steelhead,” including the White House efforts.

“Ultimately, the region as a whole must continue to advance collaborative solutions to meet the needs of the Pacific Northwest,” Johnson said. Two other federal agencies that work with Bonneville to manage the region’s dams, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation, issued statements identical to Bonneville’s.

In an interview, Johnson said the agency has had to contain its fish and wildlife spending at levels it could sustain. “The statutes direct Bonneville to operate in a business-like manner,” he said. “Like any other business, we monitor projects in our budgets and make appropriate adjustments as needed.”

Columbia River salmon recovery is one of the most expensive endangered species efforts in the country, costing Bonneville more than $20 billion since it started in 1980. But while Bonneville’s net revenues have surpassed targets in the last few years, it flatlined or reduced budgets for fish recovery at a time when, according to salmon advocates, more money is needed than ever to prevent extinctions of more Northwest salmon populations.

Proposals on the table, according to the White House and other participants in the talks, include breaching dams on the lower Snake River in southeastern Washington, funding the reintroduction of salmon into blocked areas and removing Bonneville from salmon management.

This is part two in a series produced in partnership with the ProPublica Local Reporting Network. Part one: PNW hatcheries aren’t saving salmon, investigation finds.

“We cannot continue business as usual,” the White House memo said.

But on each of those three issues, interviews and documents show, business as usual is what Bonneville has tried to preserve.

Also see (not part of this particular story, but interesting background info):

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

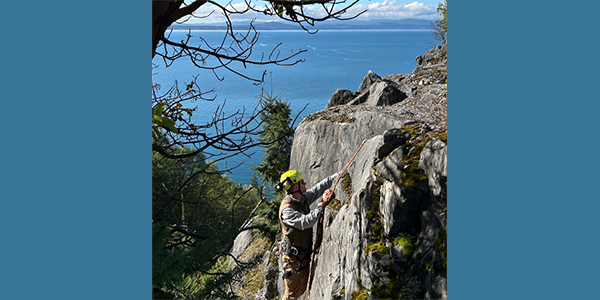

an interesting photo of grand coulee showing the 3rd powerhouse on the righthand (west) side