||| FROM SALISH CURRENT |||

People sat glued to their televisions watching the Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill 11 million gallons of thick crude oil into the pristine waters of Alaska’s Prince William Sound after striking a reef in March 1989. Thousands of oil-soaked birds, otters, fish and whales, some still alive, moved helplessly in and under the gluey blackness.

Nearly 34 years later, globs of oil still wash up on shore, and the marine habitat has still not recovered, according to scientists.

In the San Juan Islands, 1,200 miles southeast of the Exxon Valdez spill, the prospect of such an event drives the work of those passionately trying to avoid the same fate. With its fragile marine ecosystem and

tourism-based economy, the islands sit in one the busiest shipping channels in the country, and see a growing number of oil tankers and cargo vessels pass by each day.

“A major oil spill is one of the biggest threats to San Juan County … its environment and its economy [and] quality of life,” said Lovel Pratt, Marine Protection and Policy Director for the environmental protection nonprofit the Friends of the San Juans.

A sheen and a smell

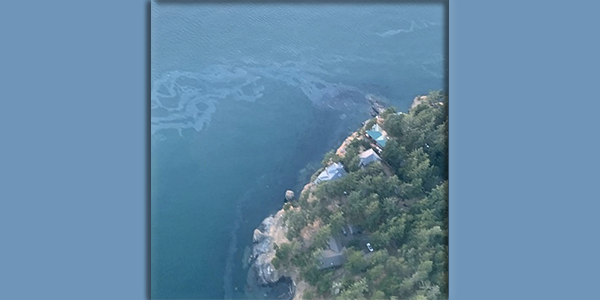

An alarm was raised on August 13 last year when an oil sheen was seen spreading off the west side of San Juan Island. The sheen, and its accompanying rotten-egg smell, were from the sinking Aleutian Isle, a 49-foot fishing vessel, which released 2,500 gallons of diesel fuel as it slipped under the surface of the Salish Sea.

The spill was rated a Type 2 out on scale of 5 (5 being the most severe), or “moderately volatile,” according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). While not considered a major spill, the incident still required a great deal of equipment and the help of numerous response agencies. It was the first Type 2 incident in Puget Sound for the U.S. Coast Guard in 15 years.

In short, it was a wake-up call.

First to respond to the spill were islanders themselves, who spotted and smelled the oil and contacted the Islands’ Oil Spill Association (IOSA).

IOSA manages a trove of equipment including a trailer of booms, floating barriers to keep oil at bay and absorbent materials. “[It’s] nothing super-fancy: basic equipment with the idea that nowadays there will be a professional response organization coming to handle the spill,” said Brendan Cowan, Director of San Juan County’s Emergency Management Department and board member of IOSA.

IOSA in turn contacted the U.S. Coast Guard, who alerted the Washington Department of Ecology, the Swinomish Tribe and whale protection agencies.

As oil seeped out of the boat, IOSA deployed booms to prevent the spread of oil. Mainland agencies arrived hours later and attempted to stop the leaking oil and to drain the vessel’s fuel tank. The situation became complicated when the boat sank, eventually resting 200 feet below the surface for 42 days before it could be raised and removed. During this time, the vessel remained a significant threat to the environment, according to Ecology, and was closely monitored for additional oil leakage, which ultimately was minimal. Many island beaches remained walled off with lines of orange boom for the last months of the summer.

Responders generally considered the response a success. Cowan said the spill response went as “good as can be expected.” Paul Hamdorf, Interim Director of IOSA during the Aleutian Isle spill, echoed Cowan, and praised the smooth communication between island and mainland responders, a result of pre-established relationships.

Deep, lingering concerns

Not everyone was happy. In September, dozens of islanders sent comments and suggestions to Ecology with concerns about how long the cleanup and boat removal took.

“[Residents] were concerned that they would like to see some of that equipment more readily available,” said Sonja Larson, the Response Technology Specialist for Ecology. “That’s a challenge we haven’t identified a solution for.”

Many islanders were concerned about the lack of equipment locally to deter endangered Southern Resident killer whales, who fortuitously were in the Port Angeles region at the time of the spill but could have been harmed had they swam through the oiled areas.

The spill was small and diesel, not crude, oil which allowed a longer response time and less robust equipment.

Future spills, however, may not be as forgiving. And as Cowan noted previously, “As much as it hurts me to say it, I think in this part of the world, at some point in time, there will be a major spill.”