||| FROM ELISABETH ROBSON |||

The foundation of this vision is far less stable than we’ve been led to believe. The bottleneck isn’t enthusiasm, or policy, or even technology, but the physical world itself.

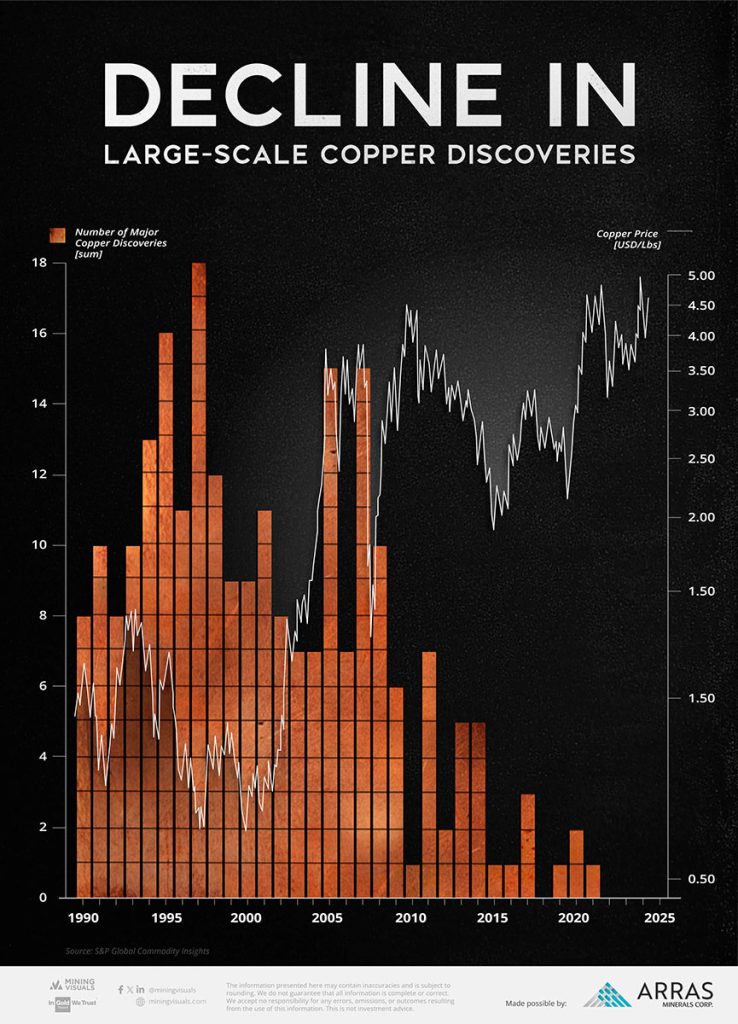

As just one of many examples of the physical limits we face, a recent article, “Running on Empty: Copper,” lays out a stark truth: copper, the metal at the core of electrification, is hitting hard physical and geological limits. It is a story about overshoot: humanity demanding more from the Earth than the Earth can provide.

Copper is the metal of electrification; the circulatory system of the entire electrical world. Every EV, every electric ferry, every charging station, every heat pump, every watt of new local generation, every computer in a data center and every cat video generated by AI requires copper. Solar panels use copper. Wind turbines use copper. Data centers, transmission and distribution wires, transformers, inverters, motors—copper, copper, copper.

Copper is not unique in this regard. Lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earth metals, and even sand all show similar trends. But copper matters because it exposes the fundamental contradiction in the story we tell about “clean energy.”

The contradiction is this: We cannot mine our way out of a crisis caused by mining.

The idea that solar panels and wind turbines and tidal machines will permanently free us from destructive extraction overlooks the vast and intensifying extraction required to build them in the first place. It treats the initial costs as temporary, the damage as incidental, and the scale as manageable. But the scale is not manageable. The electrification plans of wealthy nations and our own utility require quantities of copper and other minerals that the Earth simply cannot supply at the pace demanded.

This has direct implications for our own community. When our local utility sketches plans for local generation, microgrids, EV and ferry charging expansion, and widespread adoption of electric heating systems, those plans implicitly assume that the copper and other materials needed will be available, affordable, and environmentally tolerable. They assume that the supply chains powering this build-out are stable and that the deeper ecological costs are minimal or at least acceptable. OPALCO claims this build-out is necessary or we’ll face blackouts; it seems more likely that as the supply of finite materials drops, and the ecological and financial costs skyrocket, we’ll face blackouts no matter what we build.

The truth is that “clean energy” is only clean at the point of use. The further you trace upstream, to the mine, the pit, the acid heap, the diesel trucks, the tailings ponds, the more the fantasy of clean energy dissolves.

To call these technologies “renewable,” as OPALCO always does, is misleading. The electricity may renew itself as sunlight or tides, but the machines that harvest that energy do not. They are made of finite materials, extracted at tremendous cost to ecosystems, communities, and the climate. The land scarred by mines is not renewable. The groundwater polluted by tailings is not renewable. The species pushed to extinction by habitat destruction are not renewable.

And the copper itself is not renewable.

This is not, as some argue, a reason to cling to fossil fuels. Rather, it is a call to recognize that we cannot maintain our current levels of consumption and energy use by any means whatsoever; not fossil fuels, not solar, not wind, not tidal, not nuclear. The problem is not that we picked the wrong energy source. The problem is that we have built an entire civilization on the belief that growth is infinite, that energy can be limitless, and that the biophysical constraints of the Earth do not apply to us.

This brings us back to overshoot, and to the uncomfortable reality that “green growth” is still growth. When a utility encourages every homeowner to buy an EV, install a heat pump, add new electric appliances, charge bikes and tools and cars, and generally shift more and more of daily life onto the grid, this is not ecological stewardship. It is simply a transfer of energy demand from fossil fuels systems to mineral-intensive electrical systems. And when we include the fossil fuels require to mine and refine the materials, and build the factories and supply chains, we realize that the total footprint remains immense, and in many cases grows even larger.

Copper reveals the incompatibility of endless electrification with ecological limits. Even if we improve recycling (which we should), even if we reduce waste (which we must), the sheer scale of the so-called “transition” outstrips what recycling or efficiency gains can provide. Recycling requires metal to already exist in products; it cannot create new copper out of thin air. And most copper is already locked up for decades in buildings, grids, and long-lived equipment.

As we confront the material limits of electrification, including the tightening constraints around copper, it becomes important to look not only at the global system but at the local choices being made in our own backyard. Our utility’s recent decision to raise the base rate for an electrical connection to $67 per month reflects a philosophical choice about how the cost of the electrical system is distributed across a community.

A high base charge is one of the most regressive pricing structures a utility can adopt. It shifts the financial burden away from high-consuming, high-income households and onto those who use the least electricity, often because they cannot afford to use more. Someone who keeps their usage low, who heats with wood or limits appliances, or who simply lives in a small home or ADU, must still pay the same fixed fee as someone whose electricity use is several times higher. A family using 150 kilowatt-hours each month pays the same base charge as a household burning through 2,000. The less you use, the higher your effective price per unit becomes.

This runs directly contrary to both fairness and ecological reality. If we take the limits of copper and other materials seriously, if we acknowledge the impossibility of mining enough metal to electrify everything at current levels of consumption, then the only path that aligns with the physical world is one that reduces total demand. Yet a high base fee effectively penalizes conservation and rewards consumption.

A cooperative that sees itself as championing a sustainable future should not choose a pricing structure that weakens the incentive to conserve, nor should it put the heaviest burden on the members least able to absorb it. OPALCO should instead choose a pricing structure that embodies the logic that in a finite world, luxury consumption should not be subsidized by those living within modest means.

Our community sits at the intersection of global limits and local decisions. The copper mined in South America or Africa to supply the wires, transformers, chargers, and heat pumps for our local electrification projects carries with it enormous ecological costs: destroyed habitat, poisoned water, and broken communities. When our utility raises a fixed charge so high that it dulls the incentive to conserve, it deepens the disconnect between the story we tell about “clean energy” and the hidden damage that energy system imposes elsewhere. It shifts responsibility onto those who already use the least while enabling the pattern of overshoot that is driving global ecological breakdown.

So what does this mean for our community?

It means we must shift the conversation. Instead of asking: How can we electrify everything? we should be asking: How can we reduce our total energy use to levels the Earth can sustain?

Instead of: How do we maintain our current lifestyles with a different energy source? we should ask: What forms of living reduce our dependence on massive industrial systems altogether?

And instead of: How can we build more? we must ask: How can we live better with less?

This shift is not defeatist. It is liberating. It reframes climate and ecological action from a technological arms race, one that requires more mining, more energy, and more machines, into a cultural transformation that reduces harm at the source. It suggests that true sustainability lies not in replacing fuels, but in replacing habits; not in expanding infrastructure, but in shrinking demand; not in “green growth,” but in living within the limits of a finite world.

Copper, in its scarcity and rising extraction costs, is telling us something profound. It is telling us that the age of industrial abundance is not only ending, it must end, for the sake of the living world that sustains us. Our task as a community is to acknowledge this reality and chart a path that aligns with ecological truth rather than industrial fantasy.

Because the real question is not whether so-called “clean energy” can save our way of life and prevent blackouts. The real question is whether we are willing to change our way of life in order to save what’s left of the Earth. In the age of escalating ecological overshoot, the most ethical kilowatt-hour is not the one produced “cleanly”; it is the one we never had to generate at all.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Very well stated, Elisabeth. It is a battle against a deeply flawed and deeply rooted worldview. A confounding, delicate, and related issue that few dare to take on is what to do about population growth . . .

Thank you Elizabeth. The issue is not about population growth. It is resource consumption. Population growth is driven by resource consumption, but the overshoot is a matter of resource consumption. If we took that seriously, people would have a different attitude about population drivers. Indigenous people have understood this. As humans we think we are not a part of the resource, that we are other, when we are inextricably entwined in all resources.

Thank you Rhea. And I completely disagree with you about population. Saying overshoot “isn’t about population” is ecological denial. For 300,000 years of Homo sapiens history, population stayed in the low millions because the planet’s limits kept us there. Even after agriculture—an inherently land-hungry, habitat-destroying technology—human numbers only crept into the tens of millions. And on the eve of industrialization, after thousands of years of farming, the world still held fewer than a billion people. It was only when we began strip-mining fossil energy that population exploded to 8.2 billion, and so did our demands on soil, forests, water, minerals, and every other living system. Consumption varies, but biophysical pressure scales with bodies, and eight-plus billion bodies is an ecological impossibility and disaster. Pretending population doesn’t matter is like blaming a collapsing bridge on the trucks’ cargo, not the fact that ten thousand trucks are on it at once. Overshoot is arithmetic: too many people consuming too much. Erasing either term is politics, not ecology.

I suspect that a similar chart could be assembled for the supplies and cost of oil, with fits and starts corresponding to the emergence and decline of fracking as those resources are exhausted. Note that the steep rise in the cost of copper comes in 2000-2005, after China was granted WTO status and began cornering the markets for many consumer goods we somehow cannot live without.

A cogent piece of journalism based upon troubling facts.

I have no issue with the analysis of increased copper mining, increased consumption and skyrocketing electrical usage. There are many minerals and elements in increasing demand that pose the very same social and ecological dilemmas. Now multiplied greatly by perceived technological “needs”. Population overshoot and associated ecological overshoot are not recent developments in the human experiment.

Your “solution” Elisabeth is logical but not realistic. I have lived a middle class life very low on carbon usage and promote conservation and I sleep better at night but it has made not a whit of difference in any bigger picture analysis.

Our ideas about conservation of the public commons and cutting back and sacrificing comforts for the greater good have not happened since WWII rationing.

The monster at the door of accelerating anthropogenic climate warming is a far greater and truly a global crisis widely known after many decades of obfuscation by politicians and fossil fuel corporations that dwarfs the evil threat of Hitler. But there is no rationing of any scale in the throes of existential crisis.

Your “solution” of downsizing consumptive needs and wearing more clothes in the winter didn’t work for good ol’ Jimmy Carter and in our current governmental dumpster fire would be tantamount to individually bucketing out water above Niagara Falls in order to significantly reduce winter flow.

As in the late 1960s when I became an active conservationist then walked the talk in lifestyle and career up to now as I near my end there was hope for capitalist reawakening but such hopes are now a flickering candle flame in the wind. Nature will adapt, evolve and sort itself in a drastically different future but humankind is ignorantly racing to the cliff’s edge. In my opinion there is no other comprehensive, data-centric, realistic view of the present or likely future outcomes.

Chicken Little

One aspect often missing from conversations about copper is that humans are not immune to the neurobiological consequences of this “metal of electrification.” I say this from lived experience. I have Wilson’s disease, a genetic condition where the body cannot regulate copper, causing it to accumulate in the brain and liver.

Copper overload doesn’t just cause physical symptoms. It alters: emotional regulation, sense of meaning and connection, perception of risk and even spiritual or grandiose experiences, because excess copper intensifies dopamine and norepinephrine activity in certain brain regions.

In other words: when copper is too high, human behavior shifts. People may feel unusually inspired, visionary, spiritually attuned, or “called” while simultaneously experiencing anxiety, dysregulation, or impulsivity. These changes aren’t about personality. They are metallic, biochemical, and invisible.

So when we talk about the global copper race — mining more, refining more, accelerating electrification at all costs — we should remember this:

Copper is not a neutral material. It interacts directly with the human nervous system. And the more we destabilize ecosystems to pull it out of the ground, the more we risk destabilizing ourselves.

Sustainability isn’t just about energy sources. It’s about acknowledging that humans are biologically tied to the material world we extract from. We can’t charge forward as though the limits don’t apply to us — chemically or ecologically.

The Natural Step folks propose some basic systems-engineering conditions for sustainability on a finite planet:

“In a sustainable society nature is not subject to systematically increasing concentrations of…

… substances extracted from the Earth’s crust;

… substances produced as a byproduct of society;

… degradation by physical means,”

They go a bit further and also propose:

“and in that society… people are not subject to conditions that systematically undermine their capacity to meet their needs.”

https://thenaturalstep.org/approach/

I don’t know how this discussion can occur without incorporating the lessons learned from the ‘Peak Oil’ scare of the 20th century. As prices rise, alternatives become more viable. Most high voltage electrical lines are now aluminum. New homes almost exclusively use cross linked polyethylene for plumbing. Metal-free rotors in electric motors may soon become a reality. Fiber is rapidly replacing copper in telco applications (and that copper can be recycled).

Here is an idea: How about we slow down the forced adoption of copper-hungry ‘green’ energy solutions until they are economically viable on their own and only after they have been objectively evaluated as ‘green’? Not ‘green’ because a politician or career bureaucrat tells us so?

Check out the images of copper used in data centers: https://www.electrispower.com/blog/copper-and-ai-artificial-intelligence-perfect-partnership-in-the-world-of-modern-technologies, and read about massive increase in data center build-outs. That’s a heck of a lot of copper.

And here are some quotes from a recent article on surging copper demand (https://www.woodmac.com/press-releases/soaring-copper-demand-an-obstacle-to-future-growth/):

“Global copper demand is set to surge 24% by 2035, rising by 8.2 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) to 42.7 Mtpa … beyond AI-driven demand, the broader energy transition is fundamentally reshaping copper consumption patterns. The shift to renewable energy systems will require an additional two Mtpa of copper supply over the next decade…copper demand from the sector is projected to climb from 1.7 Mtpa today to 4.3 Mtpa by 2035, an annual growth rate of 10%… Each electric vehicle contains up to four times more copper than a conventional car… As battery technologies advance, copper demand intensity across charging infrastructure and power systems will remain high. By our forecasts, EV-related copper demand is set to double by 2035, cementing the metal’s role at the heart of the global energy transition.”

Also, I’m curious what “green” means in your use of it? (There are so many people using the word now, even the mining industry uses it. “Green mining”!! yeah right. It’s pretty meaningless!)

Whether we swap one metal (bauxite (aluminum)) for another (copper) or even plastic (fossil fuels) for copper in some circumstances like plumbing or rotors, the point is, these materials are finite, and are getting harder to access, and they all require mining which is an incredibly destructive process.

Peak Oil didn’t anticipate that fracking technology would improve so much allowing us to get to the oil in the “source rock” (shale). Of course the source rock is the last place to go for oil, so peak oil wasn’t wrong, just had the wrong time frame. We’ve still got quite a lot of tar sands to mine both here in the US and Canada for oil, although of course no one except those who make the $$ on it like the impacts of that. There’s still lots of oil left, technologies will continue to improve, and the few remaining ecosystems will probably be destroyed for that oil, along with all the metals and minerals we seem to be unable to live without. Unfortunately that means we’ll likely use every single drop and ounce we can, with all of the dire implications of that.

As Fressoz showed, there’s never been a replacement in materials (except wool) or energy in recent history; generally new advances in materials just frees up materials to be used in other ways.

In the meantime, climate change and the sixth mass extinction roll on and the final due date for the calamities they bring gets closer and closer… fiddling with subbing one metal or plastic for another while the Earth burns strikes me as yeah, absolutely something humanity will do. As so many people have pointed out to me before–what else are we gonna do? Change our ways? HA!

This notion that the price of a material like copper will simply rise to infinity due to some sort of zero price elasticity of demand is simply incorrect. In a free market, when price becomes infeasible, alternatives are sought. You call this ‘fiddling’, I call it the free market. One only needs to look at the massive graveyard of failed solar companies and the current stalling of EV sales as perfect examples of ‘green’ (not my word) energy initiatives which were forced on the people for political and financial gain of the few paid for by the many.

I’m a pretty pessimistic person, but this ‘mass extinction’ talk is really over the top and I think taking this fatalistic view is a low-effort cop-out. There is no stopping these trends, only adapting. Have we not learned this yet?

Why do you think it’s over the top? I’m not sure what else you’d call this, other than mass extinction: https://www.weizmann-usa.org/media/jexca30x/humanity_rises_as_wildlife_recedes_4.png

Or perhaps read Racing to Extinction, written by an actual endangered species biologist?

I don’t think of most dialogues like this in the Orcasonian as anything like fatalistic but rather deterministic as we speak of cause and effect and recognize that change in mass human behaviors can and have altered the course of things. Submission to fate or belief that all is predetermined, as in most organized religious beliefs is foolish and self-defeating in most human circumstances.. I agree that adaptation in some form is always necessary, now more so than ever, but I will never give in to the idea that massive ecological destruction or third world human suffering as a result of first world greed, waste, the delusion of “free-markets” and unprecedented anthropogenic species extinctions on a massive scale are inevitable. At the same time I have very little expectation that rational, science -based decisions and a wide spread willingness to reduce consumption will reshape the current arc of history. There is a small chance of creating meaningful change here.

Don’t leave out the neoliberal debt-austerity model offered by crony-capitalism.