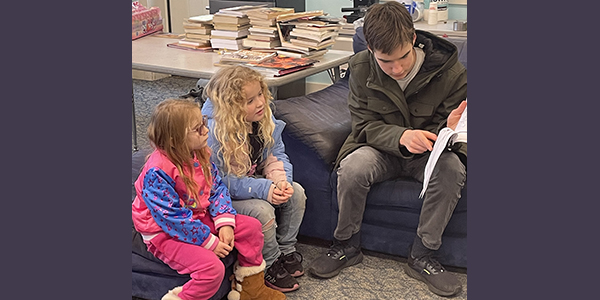

The newest member born to the J pod, J 47. Photo courtesy of Jeff Hogan, Center for Whale Research

Protection of food source and restrictions of boaters argued as key to Orca whales’ survival.

The first baby orca of the year has been born to J pod, and sited off Vashon Island on Jan. 3.

The Center for Whale Research reported in the annual Southern Resident Killer Whale (SRKW) population count that the SRKWs increased in 2009 to 87 individuals as of December 31, 2009, ” a net increase of two during a year in which three resident whales are missing and five were born,” according to the Center.

Three of the new babies were born into J pod, the most frequently observed of the three pods (J, K, and L) that frequent the Pacific Northwest inland marine waters of the Salish Sea.

No sooner had the census report been made to the government than another new baby killer whale appeared in J pod, this one to a twelve year old female on 3 January 2010! For the time being, that means the SRKW population is back up to 88! We are optimistic that this ‘baby boom’ in J pod represents a comeback for the resident population that went into steep decline in the mid 1990’s.

Now, their survival and continued population recovery depends upon sufficient food supplies (wild salmon, particularly Chinook) in future years in this region. The whales are traveling as far as California and Haida Gwai (Queen Charlotte Islands) searching for these nutritious fish, but they keep coming back to the Salish Sea.

According to a “Seattle Times” report today, the calf was spotted alongside its mother in Puget Sound between Des Moines and the north end of Vashon Island on Sunday. The birth brings to 88 the population of southern resident killer whales that frequents Puget Sound.

However the baby’s mother, born in 1998, is quite young, raising concern for the survival of both the mother and her offspring. Orcas don’t usually come into their reproductive years until they are about 15.

Births among the southern resident orcas are not unusual; last year there were five. But the youngsters often die, so they aren’t officially counted in the orca population until they are a year old.

The National Marine Fisheries Service has proposed regulations to protect orcas, including new restrictions on whale watching. The rules would create a no-go zone for recreational-vessel traffic along the west side of San Juan Island, where the orcas spend much of their time feeding in the summer months.

The feds have been getting an earful from recreational boaters, whale-watch charter operators and conservationists who argue the real issue isn’t recreational boat traffic, but rebuilding chinook salmon populations in Puget Sound for orca to eat, and reducing pollution.

The orcas depend largely on a threatened fish — Puget Sound chinook — for survival. And orcas, long-lived mammals at the top of their food chain, are among the most toxic animals in the world, because pollutants concentrate in their blubber over the years.

[intlink id=”council-urges-noaa-to-emphasize-enforcement-in-killer-whale-protection-program” type=”post”]The San Juan County Council drafted a letter[/intlink] to the Marine Fisheries Service on Jan. 5, stating its opposition to a “No Gone” zone “as proposed for the west side of San Juan Island,m” and urging enforcement of current regulations.

The public-comment period on the proposed rules, which has already been extended once, expires Jan. 15. To view the regulation and comment, go to www.nwr.noaa.gov, and click on “Proposed Killer Whale Vessel Regulations.”

For the full “Seattle Times” report, go to https://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2010738153_orca08m.html

Ken Balcomb, director of the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, doubted vessel restrictions would make any difference in orca survival. He argued that echolocation clicks made by the orcas to find food occur in a different acoustic range, so vessel noise isn’t masking sounds the whales need to hear.

“I think it’s a cop-out,” Balcomb said. “It’s let these vessels take all the heat instead of the issue of salmon and habitat.” He would rather see a no-fishing rule than a no-boating one.

Recreational-boating interests are arguing for better enforcement of the 100-yard approach limit now in place, and a go-slow, rather than no-go zone.

“Let’s monitor the enforcement, and see how it’s working, and if we need to, toughen up,” said Frank Urabeck, a consultant representing sport fishermen and other recreational interests. “To us this wouldn’t make a difference to the whales, but it would kick an industry that’s already hurting.”

The Center for Whale Research stated, “If the whales could talk to us, they would probably say that our effort to promote wild salmon recovery in the Pacific Northwest is good for all of us, so let’s do all that we can. And, lets clean up the pollution, too, so we can all eat healthy fish.”

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**