This article is the second of a two-part series about the Lopez Island community.

||| BY CHOM GREACEN |||

I worry about my children’s generation. Many young people feel the Lopez Dream of buying land and building a home is out of reach because of today’s economics. Is Lopez changing to the point where young families can no longer count on home ownership and having a public school to send their kids?

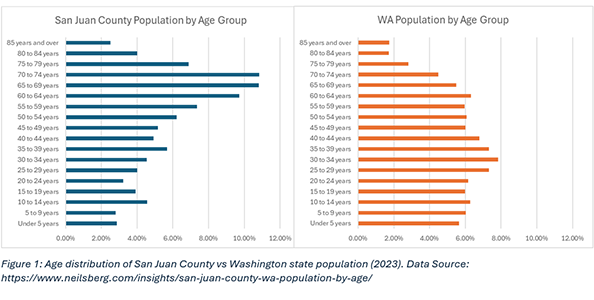

Lopez Island, like much of San Juan County, is facing demographic and economic challenges that threaten the sustainability and vibrancy of its community. The Lopez population skews elderly— with a median age of 60, even older than the county’s of 57 (Figure 1).

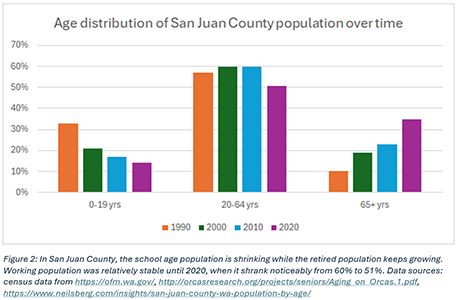

Our school-age population is shrinking while the retired segment grows. As people age, they need more services from home repair to healthcare. Working age islanders Figure 1: Age distribution of San Juan County vs Washington state population (2023). Data Source who provide the many needed services like firefighting and nursing are a declining portion of the population (Figure 2).

A declining school-age population (from 2,922 in 2000 to 2,580 in 2020) affects school enrollment, leading to less school revenues and program cuts. A school without woodshop or garden programs can deter young families from settling here, further impacting community vibrancy. This demographic imbalance endangers the intergenerational stability essential to community life.

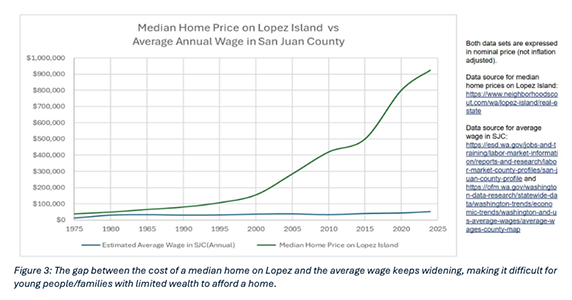

Since the 1970s, earned income for islanders has not kept pace with housing costs. Earned income has gone up about 20% since 2016, while the median home price on Lopez Island has doubled to about $957,000—equivalent to 17 years of a typical worker’s entire paychecks. This is in stark contrast to the 1980s, when a home cost about six years of earned income ($50,000) (Figure 3).

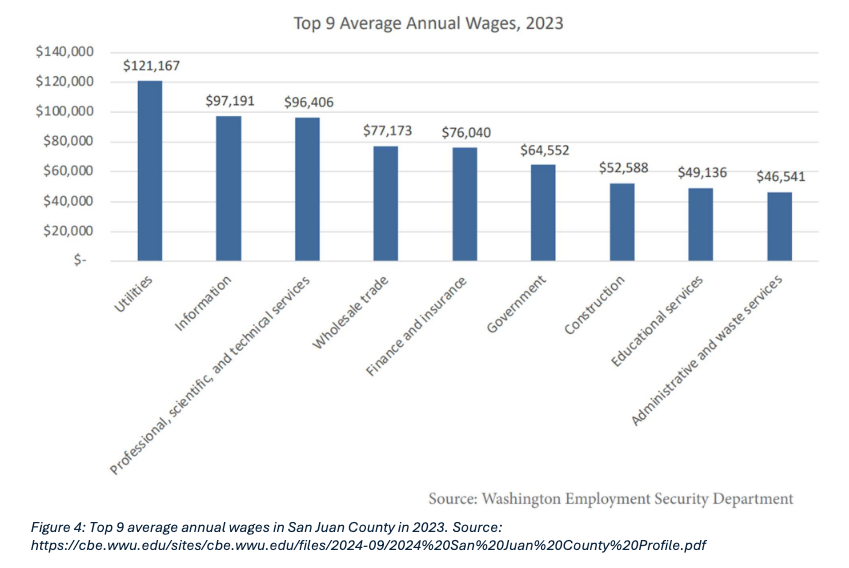

Almost half of Lopez Island’s homes are second homes or vacation rentals, further squeezing the housing market available to local residents. Unsubsidized home rental prices range from $1,8001 (According LCLT’s estimate in personal communication.) to $3,000 monthly, also unaffordable for most wage earners (see Figure 4).

It is no surprise San Juan County leads Washington in income inequality. SJC per capita income is the second highest in WA, but 39% of the population does not earn enough “to afford basic household needs” There is substantial wealth here generating significant investment/property income, but it does not translate into wage growth that keeps pace with rising costs of living for most working families.

The economic challenges facing young Lopezians stem from long-term market forces and policy decisions at all government levels, like taxes, funding and zoning. In 1994, a public loan fund covered 90% of LCLT’s affordable home costs; now 30 years later state and federal support are non-existent for LCLT, leaving them reliant on higher interest loans and private donations. Thanks to SJC voters approving a Real Estate Excise Tax for affordable housing—the only county in Washington with this—recent projects by LCLT and Housing L

Building code and regulations also contribute to increased construction costs. Living lightly and creatively was previously a common way to afford a home here. Doing so now is increasingly “not code compliant.” A heavy focus of health and safety standards has unwitting consequences of criminalizing low-cost housing options.

Many local non-profits bridge gaps between individual needs and government support, but they are also facing financial challenges due to economic uncertainty and less funding, as noted in the series’ first article.

Without action to make island living and essential services affordable and viable, Lopez may lose working families and those with limited income—people who make this place vibrant and alive. If we cannot attract and retain working-age residents, our essential services, schools, farms, and business will struggle to find the people they need to thrive.

What kind of community do we want Lopez to be? Do you want our youth to see a future here, where they can build lives, raise families and contribute their skills? Do we want our elders to have the support and care they need close to home? Do we want the Lopez Dream to be attainable?

Let’s discuss and figure this out. We can draw inspiration from the way we came together during the COVID pandemic to evaluate and meet various needs of our residents. The goal was to keep the community healthy and whole. Let’s put our heads & hearts together again and get creative.

Sandy Bishop and Clauda Costa joined the Lopez Community Land Trust float in this year’s Fourth of July parade on Lopez Island, carrying a sign that said “I Dream a World [with] Homes for All.”. Photo credit: Chom Greacen

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Thanks Chom. We all need to upgrade our attention to surviving and thriving here. That begins with transparent and honest conversations among all stakeholders. An aborted attempt to do this began in 1992 when SJC opted in to the GMA (Growth Management Act) but eviscerated the process by refusing to allow a discussion of the most significant issue: density. That conversation has never taken place. Due to successful challenges to the comp plan beginning in 1999, the least possible modifications to the density map were made in order to comply with law and ensure that SJC was not out of compliance with GMA, which translated directly into SJC’s ability to continue to receive planning money from the Department of Commerce. That the CP is now and has been irrelevant is not known by virtually everyone in the county save upper county management and the county council. Density, like Voldemort, must not be spoken aloud: “It must not be named.” Doubt this? explore https://www.islandstewards.org/the-big-picture More than ever, your participation as Chom recommends, is essential. Island Stewards mission is to foster these conversations.

I am very happy to see this sort of discussion. This is largely a self-made problem. Here is where I would start:

1. No more vacation rentals outside of areas zoned for hotels. The fact that this zoning variance is allowed has always confounded me, as it not only reduces housing supply, but also reduces quality of life for regular people trying to live in a residential-zoned area. Sadly, I have first hand experience with this.

2. Fix the daft ADU restrictions. If a property has onsite sewage and parking capacity, allow both one attached and one detached ADU. Ditch the ‘100 foot rule’. Yes, this likely takes some GMA work, but I don’t ever see the political will to do this. Why? ADUs increase supply, allow additional revenue stream with long-term renters, and help elderly people get live-in care.

3. Make building a home reasonable again. Anyone who has tried to build a home themselves here is very well versed in the red-tape nightmare we have created.

4. Allow for alternate living situations, as long as health and safety are maintained. Carve out opportunities for tiny house, yurt, and other alternate living situations.

5. Fix the owner-builder program to be more reasonable and updated with the times. Give an owner-builder more flexibility on what they can do and what they sub out.

6. Get the ports involved with providing industrial space so young people can start their own trades. We have a massive shortage of tradespeople and this only exacerbates the affordability problem.

Why is there tepid political will to take on these types of initiatives.? The answer lies in the post above this post. Saying the ‘county is full’ and trying to limit growth only makes the problem worse. We should instead be focusing on how to responsibly manage the inevitable growth and create a place where a teacher, nurse, or carpenter can still find a way to live here. Of course increasing density can be part of this solution, but that is not enough. I would like to hear more from people who are starting their lives here, as they have a very different experience than those who moved here decades ago when real estate was affordable and restrictions were loose

I started to get some hope when these type of solutions were being addressed in the runup to our council election. This subject came up during the town-hall sessions which were held. Sadly, I don’t hear much about it in our council meetings at all now. Is your council serving you or serving the status quo?

Chom’s piece really captures what so many of us are seeing across the islands. I’ve lived in tourist towns most of my life — Kauai, Newport Beach, and Sedona — and I’ve watched how every beautiful place eventually becomes both refuge and commodity. When tourism first reached islands like ours, it gave residents a sense of safety. People bought land, built homes, and believed they were creating a community where working families could build a good life. But that foundation shifted. The very people who built here are now being taxed out of what they created, as our economy evolves toward a vacation-home model that brings its own labor, its own supplies, and its own pace.

If we say we want to preserve nature, we have to recognize what that really means. Rising costs and competition will eventually keep the wild wild — but only as a luxury, reserved for those who can afford to visit. Nature will continue without us, but community won’t. So when we talk about housing for the working class, we’re talking about stewardship: ensuring that those who live here can stay here, so the people most devoted to this place and its fragile rhythm are the ones tending it.

This isn’t just a Lopez issue. It’s Orcas, San Juan, Shaw, Waldron — all of us who still want these islands to feel like home. The question isn’t whether visitors belong here; it’s whether we can still afford to. And that’s the conversation worth having together, as one archipelago.