— from Jens Kruse —

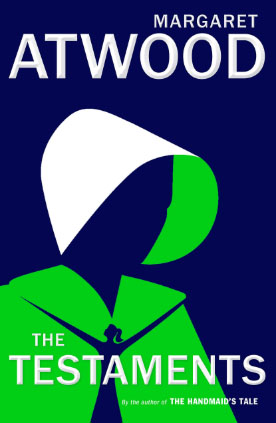

Nearly 35 years after she published The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood has published a sequel: The Testaments. The two novels are similar in some respects, yet different in others. Both end with an epilogue in which the texts that make up the body of the two novels are discussed at a supposed “Symposium on Gileadean Studies,” but in the case of the earlier novel there is one text at the center of historical examination, the “Handmaid’s Tale” told by Offred. In the sequel there are “The Testaments,” three narratives, told by three different women: Aunt Lydia, the powerful villain of the earlier novel, and two teenage women. One of them, Agnes, lives in Gilead; the other one, Daisy (which turns out to be not her real name) lives in Canada.

These narratives are identified in the novel as “The Ardua Hall Holograph” (Aunt Lydia’s tale), “Transcript of Witness Testimony 369 A” (Agnes’ tale), and “Transcript of Witness Testimony 369 B” (Daisy’s tale). Atwood alternates these narrative strands throughout the novel and weaves them together until the interaction of these lives eventually leads to events that will bring down the theocratic Gilead dictatorship. Agnes’ and Daisy’s stories (one of a young woman who has grown up in Gilead and has never known anything else, and one of a young woman who was smuggled out of Gilead and grows up in Canada looking from the outside in) are affecting and the young women’s idealism and courage plays an important role in the destabilization, and eventually the demise of Gilead.

But it is Aunt Lydia’s story that is the most fascinating, and the most revealing of the pre-history of Gilead, its early days, and its current condition. Aunt Lydia is the most powerful of the “Aunts,” the order of women that helps the Gilead patriarchy rule the female realm. Lydia had a life, and a career, prior to the events that led to the establishment of the Gilead dictatorship. She remembers how she was arrested and imprisoned, and what methods the new regime employed to convince her to collaborate with it.

At one point she reflects:

For a time I almost believed what I understood I was supposed to believe. I numbered myself among the faithful for the same reason that many in Gilead did: because it was less dangerous. What good is it to throw yourself in front of a steamroller out of moral principles and then be crushed flat like a sock emptied of its foot? Better to fade into the crowd, the piously praising, unctuous, hate-mongering crowd. Better to hurl rocks than to have them hurled at you. Or better for your chances of staying alive.

They knew that so well, the architects of Gilead. Their kind

has always known that. (178)

She writes these words during nightly, clandestine writing sessions in the inner sanctum of the library of Ardua Hall. The pages she fills she cuts to a size that allows her to hide them in a 19th century edition of Cardinal Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua. Like Winston Smith in Orwell’s 1984, she

is well aware that her writing is a seditious act punishable by death: not just because of what she writes about (the criminal and corrupt behavior and actions of the Commanders) but also because of the fact that she writes, that she records the crimes and corruption of Gilead for posterity.

Near the end of the novel, much of the material she accumulates in her pages will be smuggled into Canada where it is published in the news media to such explosive effect that it triggers the chain of events that will eventually lead to the destruction of Gilead.

At one point she asks: “Who are you, my reader? And when are you? Perhaps tomorrow, perhaps fifty years from now, perhaps never (61).”

As it turns out her writing is one of the texts, the “testaments,” that are the topic of the symposium of Gileadean Studies at the end of the novel.

And, of course, her writing is read by us, the readers of Atwood’s novel. And this, its function outside of the plot of Atwood’s novel, at least as much as its function within the novel, is the true message that Atwood is sending us: that writing has power. Not just artistic power, but also political power.

The Testaments. (New York: Doubleday, 2019) can be checked out from the Orcas Library. It is available at Darvill’s Bookstore.