||| KRUSE REVIEWS by JENS KRUSE |||

In 2004, Stephen Greenblatt, the great Shakespearean, published Will in the World: How Shakespeare became Shakespeare. In this book, which is not quite a biography, he presents us with a wealth of information about the world in which Shakespeare lived and wrote, but also admits that what we know about the man who left us with an incomparable body of writing is frustratingly sparse and incomplete. At the end of his preface, he says:

To understand who Shakespeare was, it is important to follow the verbal traces he left behind back into the life he lived and into the world to which he was so open. And to understand how Shakespeare used his imagination to transform his life into his art, it is important to use our own imagination. (14)

By now, dear reader, you might wonder if I am reviewing the wrong book, but bear with me.

In her ‘’Acknowledgements’’ at the end of Hamnet: A Novel of the Plague Maggie O’Farrell lists nine books about Shakespeare that she calls ‘’invaluable during the writing of the novel.’’ She does not mention Greenblatt’s Will in the World, which is somewhat odd, because one of the epigraphs to her novel is a quote from his article in the New York Review of Books from the year of its publication, 2004:

Hamnet and Hamlet are in fact the same name, entirely interchangeable in Stratford records in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Also, in her ‘’Author’s Note’’ at the end of her novel O’Farrell explains:

Lastly, it is not known why Hamnet Shakespeare died; his burial is listed, but not the cause of his death. The Black Death or ‘’pestilence,’’ as it would have been known in the late sixteenth century, is not once mentioned by Shakespeare in his plays or poetry. I have always wondered about this absence and its possible significance; this novel is the result of my idle speculation.

So both the scholar, in writing his non-fiction book about Shakespeare and his world, and the novelist, writing her fiction about Hamnet, his father and his family, fill the absences in their stories by employing the imagination.

And what an imagination Maggie O’Farrell brings to bear. She opens her novel with the title character as a boy coming down the stairs of his house:

Near the bottom, he pauses for a moment, looking back the way he has come. Then, suddenly resolute, he leaps the final three steps, as is his habit. He stumbles as he lands, falling to his knees on the flagstone floor. (5)

And she ends it with Hamnet’s death:

And there, by the fire, held in the arms of his mother, in the room in which he learnt to crawl, to eat, to walk, to speak, Hamnet takes his last breath.

He draws it in, he lets it out.

Then there is silence, stillness. Nothing more. (111)

In between, O’Farrell vividly – oh how vividly – evokes the life of a community and of a family in late sixteenth century England: the courtship between a most unusual woman and an ordinary-seeming man; their controversial marriage; the birth of children, among them the twins Judith and Hamnet; the escape of the husband to London, where he grows into a man of the theatre and one of the greatest writers of his and any other age. But his artistic — and commercial — success comes at the price of long separations from his Stratford community, his wife and his children.

And then, when the plague comes to Stratford, when Judith falls sick and is on the verge of death, her twin brother in effect dares death to take him instead of his sister. She recovers and he dies.

The novel is almost entirely narrated in the present tense, a rhetorical device that accounts, at least in part, for the vividness of the world and of the tale. I have tried to gesture at that vividness with the thumbnail sketch above, but to fully experience it you will just have to read the novel.

—-

But wait, the novel does not, in fact, end with Hamnet’s death. A second part ensues, roughly the last third of the story. This part is not subdivided into chapters, it is one continuous account of what follows after Hamnet’s death.

Among other things it is an evocation of grief, the grief of the family, of the siblings, and the all-encompassing, paralyzing grief of Agnes, the mother. That grief is further complicated, and intensified, by the absence of her husband who has returned to London.

This absence adds an increasing layer of irritation to Agnes’ grief. And when her stepmother, Joan, mischievously drops a playbill from her husband’s theater, advertising a play named Hamnet, into her lap, Agnes’ reaction proceeds from confusion to anger. Her mind races:

How can her son’s name be on a London playbill? There has been some odd, strange mistake. He died. This name is her son’s and he died, not four years ago. He was a child and he would have been a man but he died. He is himself, not a play, not a piece of paper, not something to be spoken of or performed or displayed. He died. Her husband knows this, Joan knows this. She cannot understand. (287)

Agnes must understand, must know, so she decides to travel to London to find out. Once at the theater, she sees this:

Hamlet, here, on this stage, is two people, the young man, alive, and the father, dead. He is both alive and dead. Her husband has brought him back to life, in the only way he can. (304)

She now understands that her husband has been and is grieving as much as she, that this play is his expression of that grief, and maybe the expression of his hope to transcend it:

She stretches out her hands to the two Hamlets, the living and the dead, as if to acknowledge them, as if to feel the air between the three of them, as if wishing to pierce the boundary between audience and players, between real life and play.

The ghost turns his head towards her, as he prepares to exit the scene. He is looking straight at her, meeting her gaze, as he speaks his final words: ‘’Remember me.’’ (305)

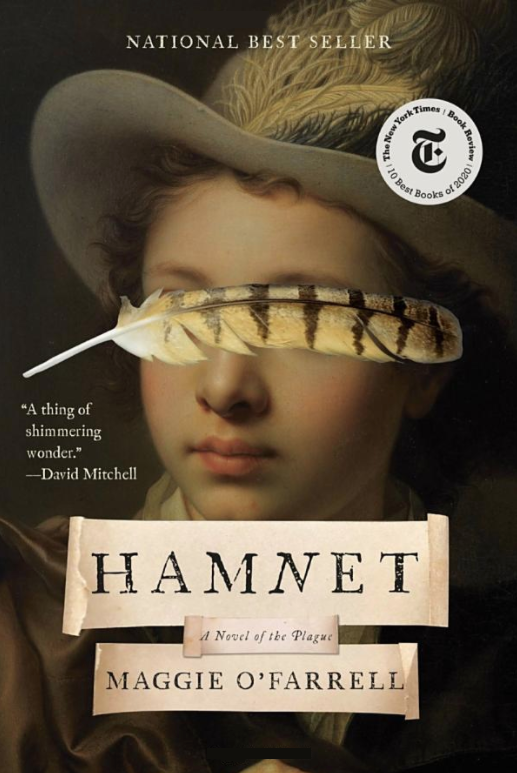

Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet: A Novel of the Plague (New York: Knopf, 2020) is available from the Orcas Library and can be obtained through Darvill’s Bookstore