||| Book review by Jens Kruse |||

Suzanne Mettler, the John L. Senior Professor of American Institutions in the Government department at Cornell University, and Robert C. Lieberman, the Krieger-Eisenhower Professor of Political Science at Johns Hopkins University, have collaborated to write a very important book for our time — Four Threats: The Recurring Crises of American Democracy.

Suzanne Mettler, the John L. Senior Professor of American Institutions in the Government department at Cornell University, and Robert C. Lieberman, the Krieger-Eisenhower Professor of Political Science at Johns Hopkins University, have collaborated to write a very important book for our time — Four Threats: The Recurring Crises of American Democracy.

Very early in their book, Mettler and Lieberman ask: “Should we contemporary Americans worry about the future of our democracy? Is it in danger” (3)?

About a year ago, I had reviewed in these pages Steven Levitsky’s and Daniel Ziblatt’ s book How Democracies Die. In it, they had approached that question by comparing the U.S. to democracies around the globe that had slid into authoritarianism or dictatorship.

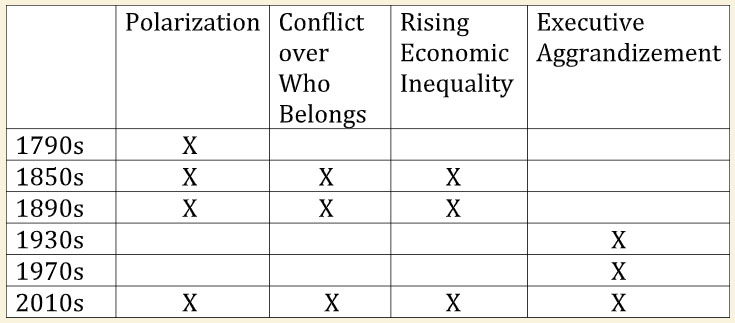

Mettler and Lieberman are well aware of and learn from Levitsky’s and Ziblatt’ s work, but they take a different approach. They first identify the main threats to democracy, namely “political polarization, conflict over who belongs in the political community, high and growing economic inequality, and excessive executive power” (5-6). They then make not other countries but the ‘’recurring crises’’ of democracy in U.S. history their points of comparison. Specifically, they examine the highly polarized 1790s, leading up to the deadlocked election of 1800; the democratic disintegration in the 1850s that eventually led to the Civil War; the backsliding in the 1890s, leading to political coups, racial pogroms, and the transformation of large section of the South into authoritarian states; executive aggrandizement in the 1930s, the expansion of executive power in response to the Great Depression; and the weaponized presidency of the 1970s, leading to the Watergate crisis and eventually the resignation of Richard Nixon.

Early in their book they visualize the occurrences of these threats in these five periods plus our own in a table.

As we can see, they eventually compare the recurring historical crises to our present. Even a quick glance at this table shows that we are living in an unprecedented and extremely dangerous moment: in none of the earlier crises were all four threats present at the same time.

They write:

From the late twentieth century onward, all four threats to democracy escalated and converged, and by the 2010s, they created a perfect storm. Into this political moment stepped a brash businessman-turned-television-personality-turned-politician, with no experience in government. He was ready to ride the storm to political victory, harnessing its fury in his quest for power, with no concern for what might be destroyed in its path. As all four threats reached high velocity and in combination generated even greater momentum, the embattled political system showed a profound lack of capacity to rein in the president. When all four threats crest in tandem, in turns out, a president and his partisan allies who control one or both chambers of Congress can threaten basic principles of American democracy in plain sight and get away with it. (212)

As a result of the confluence of these threats, Mettler and Lieberman conclude, several of the pillars of our democracy

are imperiled: free and fair elections, the legitimacy of the political opposition, and the integrity of rights.

And yet, the authors try to end on hopeful note. They point to a survey that found that:

Democrats and Republicans barely diverged in their assessments of the importance of each of the democratic

values. In other words, the value of preserving democracy may be one thing we can all agree on. As we seek to move

forward, shared democratic values may be our best hope of finding the way. (254)

But they also know how hard this will be. The way they choose to end their book serves as both an evocation of hope and a

warning:

In the most troubled time in our history for democracy, when the nation split into two sections that fought a brutal

war against each other, President Abraham Lincoln called on Americans to take part in the ‘unfinished work’ of

democracy. Speaking at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on November 19, 1863, four months after fifty-one thousand

people had been killed, suffered injuries, or gone missing there in the bloodiest battle in our history, he said, ‘It is for

us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly

advanced … that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that the government of the people,

by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.’

A year and a half later, in his second inaugural address, Lincoln re-iterated the call: ‘With malice toward none; with

charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in.’ With the spirit of magnanimity and shared citizenship that Lincoln invoked, let us carry on the work to strengthen and

revitalize democracy. (257-8)

Suzanne Mettler’s and Robert C. Lieberman’s Four Threats: The Recurring Crises of American Democracy (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020) can be checked out, by way of curbside pickup, from the Orcas Library or obtained through Darvill’s Bookstore.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Thank you for the reminder of the “unfinished work” of our nation. Please, let us not perish from the earth.

President Trump has a golden opportunity to cleanse a national wound and improve his re-electability: Nominate an unimpeachable moderate to fill the SCOTUS vacancy. [Credit to Dr. Bret Weinstein] Passing it on.