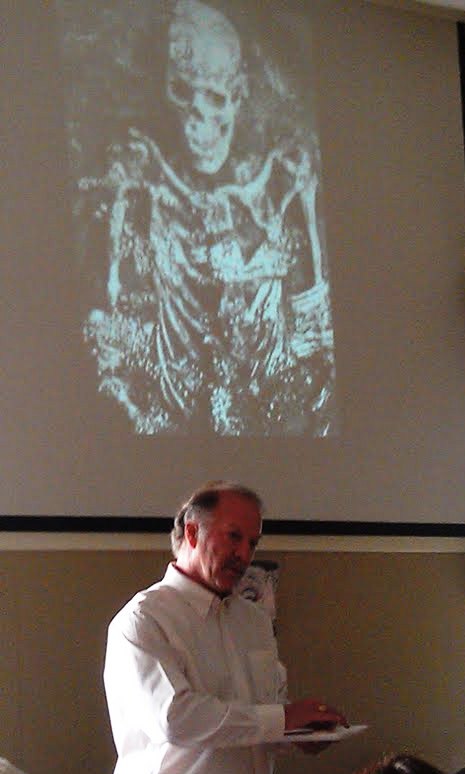

The truth lies in the bones, (or the genomes) Daniel Meatte explains at "Technologies of Prehistoric Hunting," sponsored by the Orcas Historical Society

Ancient Hunting Techniques Show Intelligence, Sophistication

Prehistoric humans demonstrated a knowledge of physics and animal behavior that was crucial to their survival, Archeologist Daniel Meatte of Washington State Parks documented in a talk on “Prehistoric Hunting Technologies” sponsored by the Ocas Island Historical Museum on Saturday, Oct. 29.

Meatte’s talk emphasized the intelligence and sophistication of Native American culture, dating to “roughly 12, 000 BCE.” Replicas of their tools were passed around the overflow audience, which, captivated by Meatte, lingered an hour past the lecture cut-off time to ask questions.

Meatte explained that the late 1990’s human genome project, which explored and mapped out the human DNA code, gave an understanding of human migration and distribution patterns in pre-history. Those patterns place the origins of human species in 70,000 BCE in Southern Africa and Central Asia to the Western Hemisphere, by 16,000 BCE. Humans spread from Asia to North America at the later date, and Washington State is on that migration “highway.”

Furthermore, research into the Bison Antiquus skull found in Ayers Pond on Orcas Island in 2005 shows that Orcas Island was one of the earliest Native American Sites in the New World. The skull, donated by the Ayers family to the Historical Society, shows marks of hunting wounds.

Meatte demonstrate the planning, design and technology evident in the variety of tools. Thrusting spears, with detachable projectile points, which allowed for deeper penetration through animal hide into internal organs. He showed cutting tools made from “flint knapping” techniques out of flint, jade, basalt, jasper, soapstone and obsidian, and explained the “cooking” techniques that showed primitive man’s understanding of heat in refining the tool. Ligatures made from dried animal parts and glues made from tree resins and other animal renderings strengthened the tools.

Understanding the characteristics of different woods such as ocean spray and syringa, and the refinement in harvesting those materials are indicated in the prehistoric tools. Darts with levers and “fletching” improved the distance and accuracy of the hunting techniques. (Dating of those techniques stem from rock art, rather than preserved artifacts, Meatte said.)

Prehistoric man “understood at what angle the stone will break with the skills of physicists,” Meatte said. He described lithic technology that is applicable today, relating the story of “the Dean of Flintknappng,” Don Crabtree, who had open heart surgery in 1978. Crabtree convinced the surgeons to use modern surgical tools on half the vertical incision, and the scalpels fashioned by Crabtree himself, using stone-age flintknapping techniques. on the upper half of his chest incision. (Modern tools left keloid, or scar tissue; the lithic tool did not

Decoration with dyes and ornamentation such as snakeskin covers indicated further value of the tools.

Bows and arrows came later prehistoric hunting technology, and Meatte asked the audience to guess “the most remarkable tool of all” — the net. Further, sites in Wyoming show that the “caveman” valued this tool by storing a game net in a rock shelf.

How did prehistoric man carry all these tools? Meatte “refused to touch” the suggestion from the audience that carrying them was “women’s work;” instead he held up a large stone from which tools as small as a needle could be chipped off.

Prehistoric man was not “primitive,” Meatte emphasized. Findings such as the Ayers Pond Bison Antiquus skull has global significance.

For more information about the Orcas Island Historical Society, go to orcasmuseum.org.

To learn more about flint knapping, go to flintknapping.blogstream.com

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**