An historical perspective

||| FROM DAVID KOBRIN |||

In a representative democracy, it is the people themselves who determine who their leaders will be. This is done through majority rule in open and fair elections. If elections are tainted by restricting voting rights, or by falsifying results, then the purpose of open and fair elections — for voters to determine leaders who represent their views – is foiled. But even when elections are honest, open, and fair, there are other complications that can completely undermine their purpose. A democratic election system assumes that those who are voting will

- understand each candidate’s position on the questions and issues to be decided

- understand the effects of each candidate’s proposals when passed and enacted

- understand how each candidate’s proposals will affect them and those they care about

All three are essential. Without them even the fairest elections are democratic in name only. Otherwise, we voters cannot know what we are voting for. If we don’t understand the consequences of our votes, then we have democracy in form only: as if we are voting blindfolded.

Any country that labels itself “democratic” assumes, most often without saying so explicitly, that people will understand the issues involved and how they affect them — and then vote in their own best interests. By voting. each is saying, “I believe the people I vote for will do the best job taking care of me and those I care about.” As Professor Denielle Allen has written, the essential question is “how to enact a commitment to a government where sovereignty resides in the people.”

hat’s why arguments over whether the United States’ form of government is a “democracy” or a “republic” are a red herring. In a true

(direct) democracy, it is those who have the vote who determine, by majority rule, the fate of every proposal that their government is

considering. In a republican form of government, those who vote determine, by their votes, who will make those decisions for them. Both systems are designed to place sovereignty in the people who have the right to vote.

Does the United States have a history of placing control of the government in the hands of its people? Have we ever had a form of government – whether a democracy or a republic — that makes sure it is the people who control what their government does?

Contrary to what most of us learned as children in school, this nation’s history clearly shows that not only have we never had a system of governing in the United States that granted deciding power to the people the intention of those who wrote the Constitution. When the authors of the Constitution, and those in power who supported their views during the centuries that followed, wrote about “freedom” and “rights” they implicitly meant only a small portion of the United States population.

Examples are abundant. The United States Constitution (1787) was written so that members of Congress were not chosen by the people they represented. With few exceptions, only white men who owned significant property had the right to vote. Even with this restriction, United States Senators were chosen by vote in the legislature of each state (Article 1, Section 3), not by direct election. This practice continued until it was modified by the 17 th Amendment in 1913. The President and Vice President were – and still are – chosen by the votes of “electors” from each state. How those electors are chosen is determined by each state’s legislature. As Philip J. VanFossen, of Purdue University, explained, the original purpose of the electors was not to reflect the will of the citizens, but rather to “serve as a check on a public who might be easily misled.” (quoted in Wikipedia). This is a subject we will return to.

This disenfranchisement of designated groups of Americans extended well beyond 1787. For instance, in the Dred Scott decision of

1857, the Supreme Court ruled that black people, both free and enslaved, were not and could not be citizens of the United States. They were not entitled to the rights and protections assured to other Americans. Women, of whatever color, were not granted the right to vote until 1922, with the passage of the 19 th Amendment. Since then, there have been changes in both directions, some more inclusive, others more restrictive. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination based on race, color, sex, or national origin. The 1965 Voting Rights Act gave the national government power to supervise elections in 15 states with a history of bias in voting.

However, that power was removed by the Supreme Court in 2013; it rescinded the national government’s power to interfere in elections in the15 states listed in the earlier Voting Rights Act.

Even this thumbnail sketch of the history of voting in the United States since its founding demonstrates that the right to vote – to have a say in one’s own government, local, state, and national — has never beeninclusive. Until the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1922, the right tovote has intentionally excluded most Americans. The reasons for this – if we are willing to face them directly – are obvious: the pervasive belief, by those in positions of power as well as their supporters, that women, white or black, people of color, and those without significant property, are less competent, less intelligent, and less able to understand economics, foreign affairs, and the overall business of governing, than their white, male counterparts.

Complicating American beliefs on “race” have been the ever-changing definitions of race in the United States. Who is “white” and who is

“black” has changed over time. Until the 1980 census, for example, Mexicans living in the United States were classified by the Census Bureau as “white”. In the mid-nineteenth century, people who emigrated from Ireland were popularly described as “black”. When all four of my grandparents arrived in the United States from Russia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, their official racial designation was “Hebrew” (although their white colored skin was also noted). The same was true of my father, uncles and aunts. Yet when I was born in 1941, under race my birth certificate said “white”. However, if I’d been an infant, arriving by ship on that same day, my race would have been “Hebrew”. The Immigration Bureau had not yet changed their racial label for Jews from Hebrew to

white.

Myths and shared historical narratives have their role in binding a nation together. But when they prevent the present from using the past to understand who we are today, then they become destructive troublemakers, fantasies to maintain the status quo. Those who refuse to accept that racism, sexism, and class deference refute the notion that the United States is, or ever has been, democratic are blinding themselves to both past and present reality. This has been an unresolved problem in the United States since its founding.

Pervasive as these issues are, none-the-less, they are not the principal reason for pessimism about the future of democracy in the United

States. Toward the close of the last century the historian Eric Hobsbawm pointed to what he saw as insurmountable threats to democracy as a formof governing by the people, for the people. (The Age of Extremes, 1994).

The first was the complexity of problems voters were expected to understand. With an increasingly intertwined global economy, corporations that were international, shifting strategic alliances among nations and secret agreements, experts in their own fields of specialization often could not agree on the nature of the problem, nor the best response. How then, Hobsbawm asked, could ordinary people, preoccupied – sometimes overwhelmed — with their own lives and problems, decide how to vote on such issues?

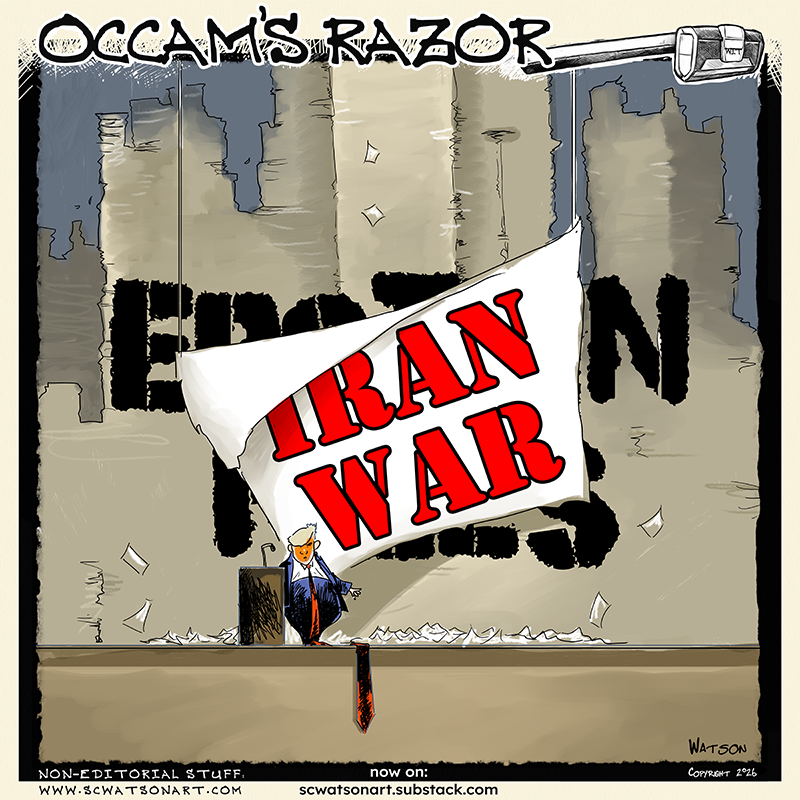

Second, Hobsbawm’s pessimism about the future of democracy as a viable form of government grew even more from his concerns about the power of propaganda. Hobsbawm had witnessed how the Nazis were able to manipulate people’s thoughts and feelings through the radio, mass rallies, bombastic and spell binding speeches, lies, scapegoating, group think, the creation of victims, and fear (among other methods).

Propaganda had changed people’s judgements and influenced their views. Such techniques, Hobsbawm wrote, focused on misinformation and emotional decisions – not the thoughtful responses needed by voters attuned to their own — or their country’s — best interests.

How much more the ability to manipulate our emotions and change our views has advanced since Hobsbawm wrote! What is possible (and happening) now makes what Hitler did seem like child’s play by comparison. For example:

- There has been significant consolidation among news, information, and entertainment sources. Many of these are owned and controlled by business interests who have priorities other than complete and accurate reporting.

- For many voters – perhaps a majority — news, views, and information Now are accessed more through social media, commentators, and “influencers” online than from other sources. Personal views are based on trust of the commentator or influencer, emotional reaction, and the reinforcement of those who are like minded. The original source of the information may not be known.

- With Artificial Intelligence, multiple realities can be created that all may appear accurate and reliable to their audience. One result is large segments of the population inhabiting differing realities, all of which are taken as “real” by their devotees.

Hobsbawm’s 1994 concerns about the future of democracy as a viable system of government is – to quote Thomas Jefferson’ comment

on the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and its expansion of slavery in the United States – “like a fire bell in the night.” We ignore it at our own peril.

What, then, does an historical perspective suggest about the future of democracy in the United States?

ÅTo be a “democracy,” or a “democratic republic,” requires a system of governing that grants ultimate power to the people, though voting, to guide their government. It assumes that voters know their own best interests, as well as the policies that are most likely to achieve the results they favor. In President Lincoln’s often quoted words at Gettysburg, in 1863, during the Civil War, the United States was fighting for a government “of the people, by the people, for the people ….” We are a country, he said, “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” A century later during the signing of the Voting Rights Act (1965) President Lyndon Johnson returned to this theme. “The right to vote,” he said, “is the basic right without which all others are meaningless. It gives people, people as individuals, control over their own destinies.”

These statements reflect the ideals established in the Declaration of Independence. The actual history of the United States, however,

reveals that the United States has never been either a democracy or a fully representative republic. To succeed as a democracy in the 21st century, we must face the pervasive racism, attacks on minorities, and discrimination against women, from the founding to the present, ugly as it is, and difficult as it may be for many to accept. Without this acknowledgement, followed by effective actions to overcome the problem, prejudice and hate will undermine claims of a representative government. It can’t be a government of the people, by the people, and for the people if some of the people are denied the vote.

Hobsbawm’s “fire bell in the night” focuses on the difficulties voters now face in understanding complex issues, as well as their own

interests. Both are essential for the act of voting to be meaningful.

What conclusion, then, about the future of “democracy” does a historical perspective suggest? What should we expect? Can

thoughtful people be optimistic? Certainly, as we’ve seen, there is muchreason for pessimism.

Unfortunately, this is our stopping point; while it might be pretty to think otherwise, no predictions should be considered reliable. After all, historians study the past, deeply, fully, sometimes with extraordinary understanding. No matter the extent to which historical knowledge can throw light on the present, it cannot predict the future.

This is where we stand today: secure in our knowledge, yet unknowing about what is yet to come.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Thank you for this thoughtful essay! One of the more unfortunate things happening is the erosion in trust in journalism

which makes fertile ground for propaganda and the rise of “social media” which allows Trump to spew his venom unchecked.

Hi David,

Your analysis of democracy’s challenges resonates deeply, particularly your point about voters needing to understand complex issues and how proposals affect them. This raises what I see as the fundamental tension of our time: the conflict between “self interest” and the “common good.”

It’s my opinion that while pursuing “self interest” is important and natural, we’ve reached a point where it actively undermines our ability to address the “common good.” The complexity of modern problems you describe makes this worse – when issues are too intricate for most voters to fully grasp, “self interest” becomes the default position, often manipulated by those with the resources to shape public perception.

Take transportation infrastructure as an example. As a transit advocate, I believe efficient transportation networks serve the “common good” socially, environmentally, and economically. Yet comparing California’s struggling high-speed rail project with China’s extensive network reveals something troubling. In our democratic system, various “self interests” – property owners, competing contractors, political actors – can effectively derail projects that would benefit the “common good.” China, despite having embraced aspects of capitalism, can still execute large-scale infrastructure projects that serve collective needs.

Now, I’m a staunch critic of China’s human rights violations and authoritarian practices like the sinicization of minority cultures. Might we think that this Left Authoritarianism is perhaps a form of racism that we similarly identify with Right Authoritarianism? But we must honestly acknowledge that their ability to subordinate “self interest” to certain “common good” objectives has produced results our democratic processes struggle to achieve.

This paradox may explain the rise of right-wing authoritarianism globally. These movements often claim that pursuing “self interest” IS the “common good,” yet they simultaneously embrace cronyism and corporate welfare that only serves particular interests. Though we must be honest – this cronyism isn’t limited to one political group. The manipulation of information you describe enables all sides to disguise “self interest” as “common good.”

The heart of the problem is this: solving “common good” challenges requires us to sometimes act outside of immediate “self interest.” But given the power corporations and wealthy interests have in shaping both policy and public opinion, we haven’t created a society capable of making these distinctions. The very complexity that makes expert disagreement common also makes it easier for powerful interests to muddy the waters, presenting their “self interest” as everyone’s interest.

If democracy’s legitimacy rests on serving the people, but “self interest” – particularly concentrated corporate and wealthy interests – increasingly prevents us from addressing the “common good,” what innovations might help us escape this trap? Perhaps we need new mechanisms that can identify and elevate genuine “common good” solutions while limiting the ability of narrow “self interests” to masquerade as universal benefits.

The question isn’t whether democracy can survive, but whether it can evolve to balance “self interest” with “common good” in an age of overwhelming complexity and sophisticated manipulation.

As for your point #2, I see a completely different situation. The Internet has ushered in an age of independent journalism never imagined just twenty years prior. For example, when the public was being mislead by a dark coalition of traditional media, politicians, bureaucrats, and pharmaceutical corporate interests, it was the brave independent journalists (two of whom live in San Juan County, with millions of listeners) who risked their personal reputation and safety to bring us the truth. Traditional media is dead and it was a self-inflicted demise.

This notion that people must be spoon-fed news from major media outlets is an antiquated and patronizing view. People can think for themselves and the free flow of information must be protected, not throttled.

As one historian to another, David, I am pleased that you have extensively mentioned Eric Hobsbawm’s classic history of the 20th century, “The Age of Extremes,” which I have read cover to cover and marked up extensively. Here is my favorite sentence from it, which I have quoted repeatedly, including in my Orcas Currents article, “Going Global”:

“There can be no serious doubt that, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, an era in world history ended and a new one began.”

Unfortunately, that “new era,” which witnessed a great burst of globalization and democratization — the latter especially in former Eastern Bloc countries — lasted only about a quarter century, to be followed about ten years ago by a period of reaction (to globalization) and polarization (both national and international).

Somehow, I think “eras” should last longer than 25 years.

To counteract the erosion of voting rights in our United States of America, we need the John Lewis Voting Rights Act to be enacted.

From Wikipedia:

“The John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2025 (H.R. 14) is proposed voting rights legislation named after civil rights activist John Lewis. The bill would restore and strengthen parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, most notably its requirement for states and jurisdictions with a history of voting rights violations to seek federal approval before enacting certain changes to their voting laws.[1] The bill was written in response to the Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, which struck down the formula that was used to determine which jurisdictions were subject to that requirement.[2][3]

On August 24, 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill by a margin of 219–212.[4] On November 3, 2021, the bill failed to pass the Senate after falling short of the 60 votes needed to invoke cloture.[5] A second attempt to pass it on January 19, 2022, as part of a combined bill with the Freedom to Vote Act, also failed. Again falling short of the 60 votes needed to invoke cloture, the bill then failed to pass a vote to be exempted from Senate filibuster rules.[6]”

To me it feels like this country has always been an oligarchy, with the trappings of a republic and the sentiments of democracy, but laid on top of rule by the wealthy (or at least, heavily influenced by the wealthy). I remember a Princeton study published in 2014 that found that, yes, we here in the US are indeed an oligarchy.

Pertinent to this discussion might also be this good essay on the “new authoritarianism”, America’s Zombie Democracy by George Packer: https://archive.ph/u7g7E

A quote:

“Today’s authoritarianism doesn’t move people to heroic feats on behalf of the Fatherland. The leader and his cronies, in and out of government, use their positions to hold on to power and enrich themselves. Corruption becomes so routine that it’s expected; the public grows desensitized, and violations of ethical norms that would have caused outrage in any other time go barely noticed. The regime has no utopian visions of a classless or hierarchical society in a purified state. It doesn’t thrive on war. In fact, it asks very little of the people. At important political moments it mobilizes its core supporters with frenzies of hatred, but its overriding goal is to render most citizens passive. If the leader’s speech gets boring, you can even leave early (no one left Nuremberg early). Twenty-first-century authoritarianism keeps the public content with abundant calories and dazzling entertainment. Its dominant emotions aren’t euphoria and rage, but indifference and cynicism. Because most people still expect to have certain rights respected, blatant totalitarian mechanisms of repression are avoided. The most effective tools of control are distraction, confusion, and division.”

Also of interest might be the book, The Next Civil War, by Stephen Marche.