||| FROM CHOM & CHRIS GREACEN |||

Our customer-owned electric utility, OPALCO, has voiced with increasing alarm: “blackouts are coming.”1 Why? Coal and natural gas-fired power plants are being retired faster than we can add new wind and solar energy, and electric load is growing with the addition of new electric vehicles and power-hungry data centers. We are entering a new reality where electricity will be in short supply and the consequences for our electric bills may be painful.

For OPALCO, the biggest crunch time is when the mercury dips well below freezing and our heaters work extra hard to keep us warm and pipes from bursting. A cold snap in December 2021 led to a spike in power consumption that resulted in a $300,000 penalty imposed2 by OPALCO’s wholesale power supplier, the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), for peak consumption exceeding the normal range. This past January cold weather triggered a similar penalty.

To make matters worse, when demand spikes, BPA has to scramble to find extra supply in the spot market, where prices can be very volatile and can surge to 25 times the normal wholesale price.3

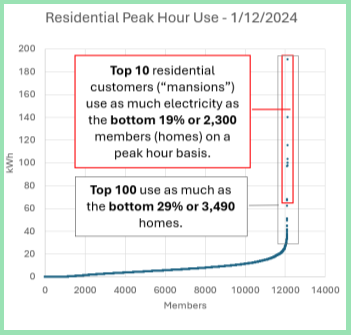

A problem is that there is a gaping mismatch between who causes the demand spikes and how much they pay to cover the system costs associated with peak demand. On 1/12/2024 when OPALCO’s system demand peaked, top 10 residential customers (“mansions”) were consuming as much as the bottom 19% or 2,308 customers! Similarly, the top 100 contributed as much as the bottom 29% or 3,489 homes. (See graph.)

Despite the deeply unequal contribution to the system peaks, OPALCO imposes the same fixed charge of $56/month that every other residential customer pays.

A fairer way to allocate costs associated with the peak consumption would be to use metered demand charge: the more one contributes to the system peak, the more they pay. If allocated based on peak usage, the top 10 customers should have been charged fixed costs of $167,000 per year, instead of the $6,720 OPALCO collected from the flat $56 per month access charge4 – an underpayment of $160,000. Similarly, the top 100 customers collectively underpaid by $547,000. OPALCO recovers this shortfall by padding everyone’s energy charge. We, the 99%, have been unwittingly subsidizing the uber-rich.

Mansion owners need to pay their fair share and be given a disincentive to not squander our limited collective energy resource, driving up the price for everyone.

1 https://www.opalco.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Anatomy-of-a-Close-Call-PNGC-R4.pdf

2 https://www.opalco.com/why-is-my-opalco-bill-so-high-this-month-cold-temps-bpa-demand-charges-and-4-rate-increase/2022/01/

3 https://www.opalco.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Anatomy-of-a-Close-Call-PNGC-R4.pdf

4 Based on OPALCO’s 2019 Cost of Service Study (https://www.opalco.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2018-Cost-of-Service-Study-Presentation.pdf) cost-reflective demand charges should be $8.30/kW to cover the costs of “wires” (distribution system). These numbers were based on 2017 data, which means the current figures could be substantially higher due to inflation, more stringent regulations, etc. If we assume a conservative inflation-driven 15% cost escalation, the demand charge would be around $9.55/kW. The other part of the demand charge is related to the penalty BPA charges for peak demand (at $300,000 per 85 MW peak, this amounts to a demand charge of $3.33/kW to cover the demand cost of purchased electricity.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

OPALCO has committed throughout 2025 to doing an extensive rate analysis. We started presenting information on this topic in our September Board Meeting. Here is a link to that presentaion: https://www.opalco.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2025-Residential-Rate-Study.pdf.

This is a critical topic that has no easy answer. We are going to be going through and weighing out the pros and cons of differing rate structures. We are trying to avoid rate shock and ensure this is fair to all of our members. Somehow we want to encourage all electric homes while discouraging wasteful energy usage.

Please get involved throughout the year. Watch OPALCO’s 2025 communications to get opportunities to dive in and learn more and provide feedback. This is an issue we need to solve as co-op together.

Perhaps a better solution would be a pricing structure more akin to water companies that are trying to encourage conservation by having “tiers” of pricing that increase per unit the more you use? OPALCO’s “service access charge” could include the right to purchase 1000 KWH every month at 12 cents. If you use more than “your share”, you pay 15 cents/KWH for the next 1000 and 20 cents for the next 1000, etc. (I don’t know what the actual numbers should be, those given are just an example) That ought to encourage conservation and force large users to fund the additional infrastructure their usage requires. I guess what I’m proposing is a system of rationing, with each OPALCO membership being allotted the right to purchase a certain amount of electricity per month at a certain rate.

Bonneville’s absurd penalty charges for unusually high usage due to weather events are not the fault of a few “mansions”; it’s just the weather. An efficient system, which we would hope the PNW electrical grid is at least be trying to become, cannot be built to readily accommodate rare ‘peak’ events. Any system built to accommodate massive but rare usage is going to be horribly overbuilt 99+% of the time and will therefore be wildly expensive and wasteful.

What if all the summer houses that are unoccupied for the winter and are thus theoretically winterized (pipes drained, etc.) get shut off when Bonneville is unable to keep up with demand? It’s not a perfect solution but there really are plenty of houses that are closed for the winter that still have the electric heatpump going to keep the house at 50 degrees or more. Frankly it’s a waste, but electricity is still cheap enough that people that can afford a second home or to winter in the south seem willing to waste that energy and pay that expense to keep their house warm while they are not using it. Doubtlessly there are complexities to this notion that would have to be worked out but surely this would help.

Energy rationing and peak-load shedding is both rational and inevitable, so why not be early adopters?

If the graphs show what is claimed, this is beyond belief… what the heck are they doing? Running the heaters with the windows open? Growing their own MMJ in an underground lab? Running a massive Bitcoin mining operation? There’s more going on here than just energy inequality.

Respect to Krista Bouchey of OPALCO for the timely reply, let’s hope you can figure out what’s going on here.

Here’s problem this article doesn’t address. We have a family home which we rent out. It’s not an Airbnb, and we have provided affordable housing to the community for 20 years.

We had one meter installed. If we took the number of folks we support on one meter, we would likely use less electricity than many folks.

But by the authors metric we are a mansion. Pretty soon we will be forced to sell because we can’t pay the mortgage and there goes more affordable housing in San Juan County.

Thanks for this thought-provoking analysis, Chris and Chom, but something must be wrong with your chart and the underlying figures. I checked my data on our house (which you visited after Dan Kammen’s Orcas Currents lecture), and we hit 213 kWh on 12 January 2024, the worst day of that bitterly cold snap. That would put us above the worst 10 residences! It’s a 2100 sf house with lots of windows, but we have insulating blinds and a 24,000 Btu/hr heat pump feeding the great room, which has to be supplemented by baseboard heaters when the temperatures drops below 25F. You (and Krista) might want to check your figures for that day.

What’s also surprising, which I neglected to add, is the large number of residences (nearly 12,000) that used less that 20 kWh in 24 hours, which means they were drawing average power of less than a kilowatt. Awfully hard to do that if you’re doing any kind of electric heating, even with a heat pump.

Reply to Krista:

Thank you Krista for your input on behalf of OPALCO. I agree OPALCO needs to discourage wasteful consumption. I’d however like to respectfully question one small point: does OPALCO really need to encourage islanders to switch from wood heating to electric heating? It makes sense to replace fuel oil or propane heating with electric heat pumps to reduce carbon emissions. But under a new reality where energy is no longer abundant and high heating load, especially on very cold days, could lead, and have led, to a LOT more expensive power purchase from the spot market, wood heating should really be thought of as a friend, not a foe. It’s a carbon free, renewable energy resource, so I hope OPALCO will reconsider the practice of considering wood heating as undesirable as propane or fuel oil heating. Sustainably harvested wood can be done in a way that helps improve forest health and reduce the wildfire risks. If some households have been using firewood as their primary source of heat, it may no longer make climate or energy sense for OPALCO to pay them a $1500 rebate to encourage them to move away from wood heating and add their heating load to the anticipated growing energy deficit situation.

Reply to David Bowman:

I wish I knew the answer! But a contractor friend of mine did share that he worked on installing electric heating elements under outdoor concrete walkways at a fancy mansion on San Juan Island. When the temperature drops below a certain threshold, these walkway heaters could automatically come on all at once, heating the cold crisp outdoor air, spiking the peak consumption, and raising the electricity costs for everyone.

Reply to Michael Riordan:

The graph shows kWh consumption in ONE hour, not 24 hours. I used the maximum HOURLY consumption that happened on that cold day, provided by OPALCO. It’s the same graph as Slide 6 from the presentation, the link to which Krista’s comment pointed to. But the one shown on OPALCO’s slide cut off the very top users. Hope this helps.

As for the low consumption users, I think a good portion of them might be seasonally occupied homes that were vacant during that cold day. So their peak demand might happen on a different day when the homes are occupied.

Reply to Colin Williams as well:

What is the size of your transformer? For a residential customer to be able to have peak consumption in the range of 30 kWh or higher in one HOUR (not a day), they must have a 400 Amp or >400 Amp transformer to be able to draw that much power from the grid. There are only 223 residential customers with >400Amp service in OPALCO’s territory.

A typical home in San Juan County consumes about 1,000 kWh/month. OPALCO’s average load factor (ratio between peak vs average consumption in a year) is around 30%. This means, a typical home will have peak consumption of around 3.4 kW (or 3.4 kWh in ONE hour). Houses that are less efficient or have multiple dwelling units or larger than average will likely have peak demand that is a few times higher than 3.4 kW, but not likely 9+ times that of a typical home. Regardless, at least we can agree on the principle of people paying their fair share of the system costs?

While it might be safe to say the top 10 users are likely “mansions,” I agree it might be a stretch to call all top 100 users “mansion owners.” Perhaps I was being sensational, but my point is that the power consumption pattern is deeply unequal and it is not equitable for the biggest (and likely wealthier) power users to be subsidized by the rest of the community.

OK, I understand the source of my confusion — I was thinking these were 24 hour kWh consumption figures, not peak hourly consumption. But then these numbers are truly obscene, unless they are distributed over several households like Colin Williams indicates. The topmost (residential?) user was drawing 195 kW that night, compared to something over 10 kW for our house. I agree that such users should be paying (perhaps much) more than the standard fixed cost of $56 per month, as their peak demands are a significant portion of the peaking power that OPALCO has to buy from the grid at much higher rates per MWh.

Very interesting article Chom and Chris. Thank you for sharing your observations with the public.

Likewise, I’ve always thought that giving resource usage discount rates in regards to high volume users (of any of our shared resources), that are businesses catering to the tourist industry (including vacation rentals, lodging establishments, and annual events), to be illogical, unfair, and not representative of the common good.. After all, they’re a commercial entity that profits from it.

It makes me feel somewhat indignant knowing that my money is being spent to support an ever-increasing infrastructure, (and the maintenance thereof), that’s designed to handle a million tourists a year, especially when knowing the coming impacts of ecological overshoot, and climate change are soon to be upon us.

A similar comment can be made about the treatment of large, commercial users of water by Eastsound Water Users Association. A former EWUA board member and president have both told me that several such entities are not paying their far share of the fixed costs of producing their water supplies, which peak in July and August when the island population doubles due to the tourist influx.