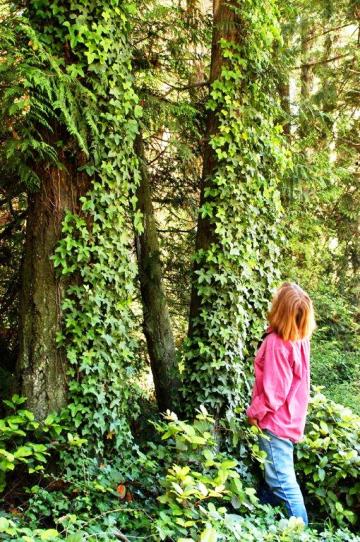

English Ivy is an attractive vine that is widespread in Western Washington and the San Juans. It is an ornamental that is often planted intentionally but has become an invasive plant in forests, woodlands and parks throughout the region.

English Ivy vines are evergreen, grow vigorously year round and are well adapted to the mild Pacific Northwest climate. In the understory of forests English Ivy spreads over the ground crowding out and killing native wildflowers, ferns and tree seedlings. These ivy vines make thick mats that are often perfect hosts for pests such as rats. Since ivy roots can be thick and shallow rooted , they often degrade the integrity of sloped areas and lead to erosion. On walls and fences they can grow into the wood and mortar causing structural and aesthetic damage. When they are allowed to grow up into trees they often affect tree health by increasing the likelihood of bark disease. Trees are more likely to blow down due to the sail effect of the large mass of ivy in the tree. It can also reduce the light to tree branches because of the covering ivy.

English Ivy varieties vary in leaf size and shape from small narrow leaves to large broadly shaped leaves. They can be deeply or shallowly lobed. However, they are recognizable to most as heart shaped, shiny leaves that grow in dense whorl-like clusters and produce umbrella like groups of small greenish yellow flowers in the fall followed by dark purple to black berries in the late winter or early spring. Immature ivy leaves tend to be lobed and mature heart-shaped. As ivy climbs, it puts out small rootlets that exude a sticky substance allowing them to stick to most any surface. Older vines can be tree-like and as much as five inches thick.

It takes ivy about 10 years for it to climb, mature, flower and produce seeds which are then spread throughout the islands by starlings and other seed eaters. Since it is shade tolerant, well adapted to our climate, and does well in almost any soil, it roots almost everywhere a seed is dropped.

Control of English Ivy is best achieved with physical removal. Hand pulling, with the aid of a shovel to loosen soil and remove root fragments, is relatively easy due to the sturdy stems that are not deeply rooted. Ivy plants which are growing on trees can be controlled by cutting the vines from the lower trunk after prying them off, and removing the vines from the ground. The upper vines will die if not rooted in the ground although this may take several months. Pulling upper vines from the tree can be dangerous as weakened branches may fall. Mulching all areas where the vine has been removed will decrease the chance of regrowth of the ivy and other undesirable weeds. In large areas the ivy mats can be rolled up like carpet and left to rot or disposed of as yard waste.

Four cultivars of English Ivy (Hedera helix ‘Baltica’, H. helix ‘Pittsburgh’, H. helix ‘Star’, and H hibernica ‘Hibernica’ ) have been placed on the Washington State Noxious Weed List as Class C noxious weeds and have been selected for control county-wide by the San Juan County Noxious Weed Control Board. Control and containment of spread is required by law because of the negative impacts of this vine on the natural environment.

Article submitted by: Kate Yturri, Judy Winer and Gwen Stamm, recent graduates of the WSU Master Gardener’s Course.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Keep it up, you three. We all need to be educated.

Pulling English Ivy can be almost enjoyable (though messy), as the roots with their tendril-like fingers come up quite easily, and you can be left with 20 feet or more of root/stem to coil up and dispose of..

I’d think Clematis Vitalba can be controlled in the same manner; remember the trees along Lovers Lane?