Dave Zoeller (on the left) at the finish of "The Great Tibetan Marathon" July 18, 2009

Just back from “The Great Tibetan Marathon” at Ladakh, the northernmost province of India, bordered by China and Pakistan, Dave Zoeller, otherwise known as Z, is still digesting the experience.

His journey to Ladakh was ignited by the opportunity to run a marathon there, which he successfully completed on July 18. Last winter, Z was in search of a unique location for a marathon run celebrating his 60th birthday. A 35-year resident of Orcas Island, previously his runs had been mostly in the Northwest. He’s run many half-marathons, and three marathons – 26-plus miles.

He found the Ladakh tour being coordinated by a Danish company that organizes international “adventure” marathons, which dovetailed nicely with his interest in “the roof of the world.”

Z’s curiosity about Central Asia and Tibet’s history and culture was piqued when his younger son gave him an article written by the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s leader in exile. Z wanted to learn more than the “media-generated ‘Tibet – good; China – bad’” stereotypes he found prevalent in popular literature.

His reading led him to obtain books from the Library of Congress, such as the Ladhaki Phrase Book, acquired with the assistance of the Orcas Public Library.

Thus, during his trip, he was able to greet Ladakhi kids with “Hi” and “How are you?” in their own language o the marathon. “Hey that white boy speaks Ladaki!”

The trip got off to a delayed start when Z’s flight to Sea-Tac from Orcas was canceled due to fog. When he got to the airport for his flight to New York and then on to Delhi, India, his plane had already left. So he booked a flight west through Seoul, Korea, to meet up with his marathon cohorts in Delhi before flying to Leh, the main town in central Ladakh. That flight too can be iffy, due to the high altitudes, and is often delayed or canceled.

Z arrived in Leh 9 days before the race was to begin, in order to become acclimatized to the high altitude. He found, through pre-race trials, that he needed to adjust his pace to alternate running with a brisk walk so that his breathing didn’t become too labored. He says, “In the end the altitude was the biggest challenge — I couldn‘t do what I was trained to do.” His race time was about five hours, an hour longer than his usual marathon time.

The race began 30 miles from Leh at the Hemis monastery, with a blessing and the start announced by the bellowing from the long, traditional Tibetan horns. Monks at the Spituk monastery, as well as local people, greeted the finishers, with a post-run party.

The Danish organizers had worked with the local schools to include young kids running in the shorter runs, and a 17-year old student from Leh won the marathon, beating “some really good runners” by half an hour, said Z. The student will be sponsored by the Danish organization in a marathon in Delhi later this year.

Bur for Z, he says, “In the end, the marathon was a minor part of it — if it’s hard enough you feel like you’ve done something.”

While the marathon was “the excuse or the spark that got me there,” Z’s reading had led him to the determination that at some point he was “going to have to go there and experience it.”

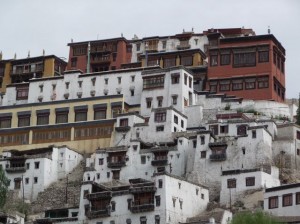

One of the larger monasteries in Ladakh, where Z found Buddhism is "Alive and Well!"

Through his experiences in Ladakh, he found that, with “prayer wheels and temples everywhere and every mountain having its own Deity…my sense is their lives have no separation from the spiritual world.

“The people are constantly aware… there are prayer flags everywhere stating, ‘The gods are victorious.’

“It’s hard to go away from the experience of the pervasiveness of the religious aspect without having a lot of admiration for it.”

Traditionally the crossroads of High Asia, Ladakh is a high, dry, desert plateau, an ancient kingdom that lies north of the Himalyas. The Indus River flows through the province’s valley, and the area is one of the highest, permanently inhabited areas of the world. The average elevations range from 10,000 to 13,500 feet.

The local population is about 80 percent Buddhist and 20 percent Muslim, and Z found a life-and-let-live attitude towards the differences. In particular, Z was struck by his tour’s local guide, who was “somewhat westernized,” but tolerant and accepting.

“We’re constantly judging,” said Z. “It sure seems like they don’t have the need to make these judgments, and it’s pretty refreshing.”

Ladakh has been open to tourists since about 1980, and has been exposed to the Western world for only about the last 50 years. It has gone through the phase when everything western is seen as glamorous to perceptions that in evolving from a traditional to a money economy, traditional culture is lost.

They ask tourists to respect their culture and not dress in clothing that reveals legs, backs or shoulders and refrain from holding hands or other forms of affection in public.

“To a large extent, they show tourists respect. They’re a very polite society,” said Z.

Poverty is not obvious, as in Delhi or Jaiphur; Z saw one beggar with a baby on the streets of Leh, a town of 40,000 with one main market street. “People seem to be well-nourished and cared for, though not affluent.

“There is certainly not the main tourist trappings of India – the taxis, tour operators and merchants.”

He also noted a pervasive military presence of the Indian army, as the northern province is threatened by the presence of Chinese and Afghanistani military on its borders.

With its long history of all kinds of people come through the crossroads of Leh, Z found that most people he talked to appreciated the security that the presence of the Indian army brought.

Z found that the people are “remarkably adaptive… with an emphasis on good — no wonder people want to come there; there’s something valuable in the place and the people in and of itself.”