— from Russel Barsh, Kwiaht Director —

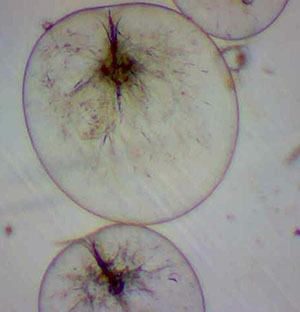

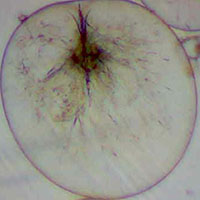

Photo: Sarka Martinez, SoundToxins

The bright orange “bloom” that appeared along the East Sound shoreline yesterday is a harbinger of spring, and its timing reflects the vast difference in weather patterns between 2016 and 2017. The organism responsible for the bloom is Noctiluca scintillans, a large dinoflagellate that looks like a waterlogged plastic bag under a dissecting microscope. SoundToxins volunteer Sarka Martinez sampled the bloom and confirmed the culprit.

Dinoflagellates are very unusual organisms that combine characteristics of both animals and plants. They contain chlorophyll and can photosynthesize; they also engulf and feed upon a variety of tiny algae and animals in the plankton, especially at night. Dinoflagellates can move up and down in the water column with a whip-like flagellum, and most of them are protected by a number of interlocking armor plates composed (remarkably) of cellulose.

Noctiluca is an exceptional dinoflagellate in several respects. It is very large, it lacks armor plating, and it contains tiny organelles that can flash at night producing “sea sparkle”. Noctiluca appear to have nano-phytoplankton living in their baggy “skin,” which gives them their color.

Noctiluca is always in our waters in small numbers. The right combination of warm water, accumulated nitrates and other nutrients in the water, and a little sunshine gives this organism a boost, and it can reproduce so quickly that within hours it can “bloom” visibly and make up over 90 percent of all of the plankton along our more protected shorelines.

Over the years, researchers for SoundToxins and Kwiaht have seen the first orange bloom of the year in East Sound vary by several months. During the exceptionally warm, dry winters of 2015 and 2016, blooms appeared in some parts of the islands as early as March. In other years, there were no discernible orange blooms until June. Compared to last year, this year’s first bloom is relatively late, reflecting cooler, wetter La Niña conditions.

Noctiluca is not toxic, but it can accumulate to the point that it packs the gills of small fish, suffocating them; and when the bloom dies and settles on the bottom, bacterial decomposition uses up a significant share of the oxygen dissolved in the water, sometimes suffocating cockles, clams, and other animals that live in the sand and mud. The clearing effect of a Noctiluca bloom, furthermore, can facilitate a follow-up bloom by a toxic dinoflagellate species that is less visible, but more problematic.

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Thanks to Russel, as always, for explaining what appears in our own backyard and of which we otherwise would not have a clue.