What threatens local newspapers now is not just digital disruption or abstract market forces. They’re being targeted by investors who have figured out how to get rich by strip-mining local-news outfits. The model is simple: Gut the staff, sell the real estate, jack up subscription prices, and wring as much cash as possible out of the enterprise until eventually enough readers cancel their subscriptions that the paper folds, or is reduced to a desiccated husk of its former self.

||| FROM THE ATLANTIC (SUBMITTED BY A READER) |||

The Tribune Tower rises above the streets of downtown Chicago in a majestic snarl of Gothic spires and flying buttresses that were designed to exude power and prestige. When plans for the building were announced in 1922, Colonel Robert R. McCormick, the longtime owner of the Chicago Tribune, said he wanted to erect “the world’s most beautiful office building” for his beloved newspaper. The best architects of the era were invited to submit designs; lofty quotes about the Fourth Estate were selected to adorn the lobby. Prior to the building’s completion, McCormick directed his foreign correspondents to collect “fragments” of various historical sites—a brick from the Great Wall of China, an emblem from St. Peter’s Basilica—and send them back to be embedded in the tower’s facade. The final product, completed in 1925, was an architectural spectacle unlike anything the city had seen before—“romance in stone and steel,” as one writer described it. A century later, the Tribune Tower has retained its grandeur. It has not, however, retained the Chicago Tribune.

To find the paper’s current headquarters one afternoon in late June, I took a cab across town to an industrial block west of the river. After a long walk down a windowless hallway lined with cinder-block walls, I got in an elevator, which deposited me near a modest bank of desks near the printing press. The scene was somehow even grimmer than I’d imagined. Here was one of America’s most storied newspapers—a publication that had endorsed Abraham Lincoln and scooped the Treaty of Versailles, that had toppled political bosses and tangled with crooked mayors and collected dozens of Pulitzer Prizes—reduced to a newsroom the size of a Chipotle.

SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL NEWS SOURCE

Spend some time around the shell-shocked journalists at the Tribune these days, and you’ll hear the same question over and over: How did it come to this? On the surface, the answer might seem obvious. Craigslist killed the Classified section, Google and Facebook swallowed up the ad market, and a procession of hapless newspaper owners failed to adapt to the digital-media age, making obsolescence inevitable. This is the story we’ve been telling for decades about the dying local-news industry, and it’s not without truth. But what’s happening in Chicago is different.

In May, the Tribune was acquired by Alden Global Capital, a secretive hedge fund that has quickly, and with remarkable ease, become one of the largest newspaper operators in the country. The new owners did not fly to Chicago to address the staff, nor did they bother with paeans to the vital civic role of journalism. Instead, they gutted the place.

Two days after the deal was finalized, Alden announced an aggressive round of buyouts. In the ensuing exodus, the paper lost the Metro columnist who had championed the occupants of a troubled public-housing complex, and the editor who maintained a homicide database that the police couldn’t manipulate, and the photographer who had produced beautiful portraits of the state’s undocumented immigrants, and the investigative reporter who’d helped expose the governor’s offshore shell companies. When it was over, a quarter of the newsroom was gone.

The hollowing-out of the Chicago Tribune was noted in the national press, of course. There were sober op-eds and lamentations on Twitter and expressions of disappointment by professors of journalism. But outside the industry, few seemed to notice. Meanwhile, the Tribune’s remaining staff, which had been spread thin even before Alden came along, struggled to perform the newspaper’s most basic functions. After a powerful Illinois state legislator resigned amid bribery allegations, the paper didn’t have a reporter in Springfield to follow the resulting scandal. And when Chicago suffered a brutal summer crime wave, the paper had no one on the night shift to listen to the police scanner.

As the months passed, things kept getting worse. Morale tanked; reporters burned out. The editor in chief mysteriously resigned, and managers scrambled to deal with the cuts. Some in the city started to wonder if the paper was even worth saving. “It makes me profoundly sad to think about what the Trib was, what it is, and what it’s likely to become,” says David Axelrod, who was a reporter at the paper before becoming an adviser to Barack Obama. Through it all, the owners maintained their ruthless silence—spurning interview requests and declining to articulate their plans for the paper. Longtime Tribune staffers had seen their share of bad corporate overlords, but this felt more calculated, more sinister.

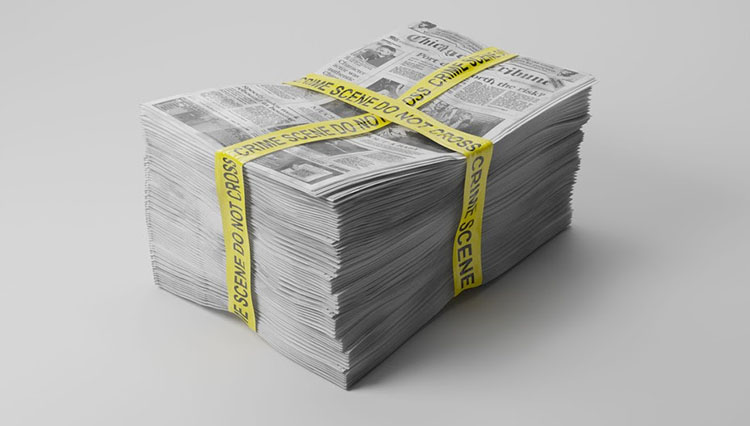

A stack of Chicago Tribune newspapers, tied together as a bundle with yellow police tape that has black text “Crime Scene Do Not Cross”

Ricardo Rey

“It’s not as if the Tribune is just withering on the vine despite the best efforts of the gardeners,” Charlie Johnson, a former Metro reporter, told me after the latest round of buyouts this summer. “It’s being snuffed out, quarter after quarter after quarter.” We were sitting in a coffee shop in Logan Square, and he was still struggling to make sense of what had happened. The Tribune had been profitable when Alden took over. The paper had weathered a decade and a half of mismanagement and declining revenues and layoffs, and had finally achieved a kind of stability. Now it might be facing extinction.

When Alden first started buying newspapers, at the tail end of the Great Recession, the industry responded with cautious optimism. These were not exactly boom times for newspapers, after all—at least someone wanted to buy them. Maybe this obscure hedge fund had a plan. One early article, in the trade publication Poynter, suggested that Alden’s interest in the local-news business could be seen as “flattering” and quoted the owner of The Denver Post as saying he had “enormous respect” for the firm. Reading these stories now has a certain horror-movie quality: You want to somehow warn the unwitting victims of what’s about to happen.

Of course, it’s easy to romanticize past eras of journalism. The families that used to own the bulk of America’s local newspapers—the Bonfilses of Denver, the Chandlers of Los Angeles—were never perfect stewards. They could be vain, bumbling, even corrupt. At their worst, they used their papers to maintain oppressive social hierarchies. But most of them also had a stake in the communities their papers served, which meant that, if nothing else, their egos were wrapped up in putting out a respectable product.

The model is simple: gut the staff, sell the real estate, jack up subscription prices, and wring out as much cash as possible.

READ FULL ARTICLE: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/11/alden-global-capital-killing-americas-newspapers/620171/

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**

Seems like “Fundamentally Transform” is sinister, viral catch phrase for our adrift culture. I’m grateful to be old enough to remember a handful of easier moments, however brief!