The Lummi Nation is dropping live salmon into the sea in a last-ditch rescue effort: ‘We don’t have much time’

— from Levi Pulkkinen (The Guardian) in San Juan Island, Washington —

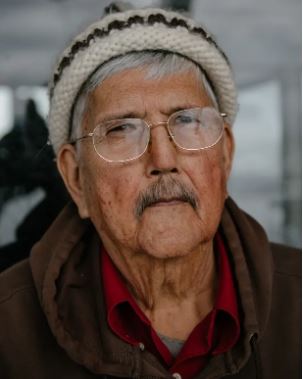

Bobbing on the gray-green waters west of Washington state’s San Juan Island, Sle-lh’x elten Jeremiah Julius lifted a Chinook salmon from a 200-gallon blue plastic fish box. He carried the gulping fish to the boat’s rail and slid it into the sea, where it lingered a moment, then disappeared in a silver flash.

It was a quietly radical act.

This sea once teemed with the giant salmon, which in turn sustained thriving pods of orca. Today wild Chinook fisheries are in decline, and the orcas are starving. Julius is the chairman of the Lummi Nation, a tribe pushing an unorthodox policy. They are feeding salmon to the wild whales.

Numbering close to 100 two decades ago, the population of southern resident orca has dropped to just 75 as a result of pollution in their environment, ship noise that drowns out their sonic communication and hinders their hunting, and, most crucially, a paucity of wild Chinook. Older whales have been seen wasting away, miscarriages are on the rise, and infant orca born alive are not surviving to adulthood. Last year a mother whale, Tahlequah, carried her dead calf for two and a half weeks in a scene that sparked an international outcry.

The Lummi Nation has long shared a coast and culture with the whales, an orca community found only in the waters off Seattle and Vancouver known as the Salish Sea. The tribe’s members once lived on the shores of the San Juans, now dotted with quaint tourist towns, million-dollar vacation homes and resorts, and they see the whales as their relatives.

The fish slipped to the orca was both a prayer and a signal to the starving whales that the tribe would not sit back and watch them vanish.

Before the Chinook was returned to the water, a Lummi drummer sang the story of a great flood said to have brought the tribe to the islands. The Lummi consider themselves to be survivors of that long-ago flood; the survivor’s song is their nation’s anthem. But they worry they, the salmon and the orca will not survive the present disaster.

“The bottom line is the Salish Sea and the whales and the tribes need more salmon,” said Julius, the elected leader of the 6,500-member tribe. “We’re at the point now where we don’t have much time. We are possibly the last generation that can do anything about it.”

READ FULL ARTICLE:

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/25/orca-starving-washington-feed-salmon-lummi-native-american

**If you are reading theOrcasonian for free, thank your fellow islanders. If you would like to support theOrcasonian CLICK HERE to set your modestly-priced, voluntary subscription. Otherwise, no worries; we’re happy to share with you.**